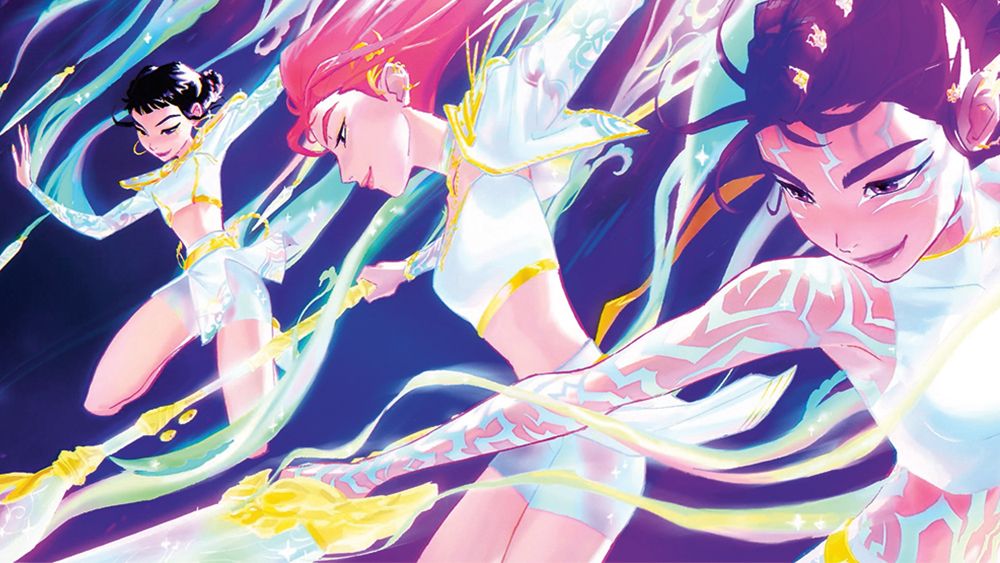

Who knew that the best way to battle KPop demons is through concept art? The 2025 Concept Art Awards have just crowned the winners, showcasing everything from otherworldly creatures to the art of making wicked characters look *very* chic.

Honestly, if I had a dollar for every time I needed a storyboard for my daily life drama, I could fund my own art awards! It’s clear that when creativity meets chaos, the results are simply magical. Maybe I should start sketching out my morning coffee routine—who knew caffeine could be so inspirational?

So, grab a pencil and start doodling your own epic tales. You never know; your art might just slay the next big trend!

https://www.creativebloq.com/art/digital-art/the-concept-art-awards-2025

#ConceptArt #KPop #ArtAwards #CreativityUnleashed #DemonHunters

Honestly, if I had a dollar for every time I needed a storyboard for my daily life drama, I could fund my own art awards! It’s clear that when creativity meets chaos, the results are simply magical. Maybe I should start sketching out my morning coffee routine—who knew caffeine could be so inspirational?

So, grab a pencil and start doodling your own epic tales. You never know; your art might just slay the next big trend!

https://www.creativebloq.com/art/digital-art/the-concept-art-awards-2025

#ConceptArt #KPop #ArtAwards #CreativityUnleashed #DemonHunters

Who knew that the best way to battle KPop demons is through concept art? 🎨✨ The 2025 Concept Art Awards have just crowned the winners, showcasing everything from otherworldly creatures to the art of making wicked characters look *very* chic.

Honestly, if I had a dollar for every time I needed a storyboard for my daily life drama, I could fund my own art awards! It’s clear that when creativity meets chaos, the results are simply magical. Maybe I should start sketching out my morning coffee routine—who knew caffeine could be so inspirational?

So, grab a pencil and start doodling your own epic tales. You never know; your art might just slay the next big trend!

https://www.creativebloq.com/art/digital-art/the-concept-art-awards-2025

#ConceptArt #KPop #ArtAwards #CreativityUnleashed #DemonHunters

0 Reacties

·0 aandelen