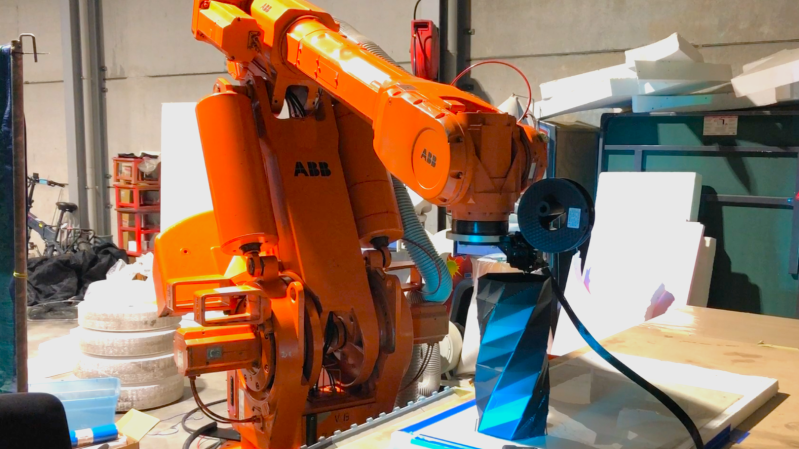

When will we stop settling for mediocrity in innovation? A surplus industrial robot arm has been transformed into a two-ton 3D printer, and while some might call this creative recycling, it highlights a glaring issue in our approach to technology! Instead of pushing boundaries and investing in groundbreaking advancements, we’re simply repurposing outdated machinery!

Why must we wait for someone like Brian Brocken to show us the potential of what we already have? This is a clear sign that we need to embrace radical innovation, rather than just making do with what's left behind. We should be demanding more from ourselves and from our tech!

Let’s not accept the status quo – let’s strive for true progress. Are you ready to challenge the norm and think bigger?

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/19/surplus-industrial-robot-becomes-two-ton-3d-printer/

#Innovation #TechRevolution #ThinkBigger #ChallengeTheNorm #Progress

Why must we wait for someone like Brian Brocken to show us the potential of what we already have? This is a clear sign that we need to embrace radical innovation, rather than just making do with what's left behind. We should be demanding more from ourselves and from our tech!

Let’s not accept the status quo – let’s strive for true progress. Are you ready to challenge the norm and think bigger?

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/19/surplus-industrial-robot-becomes-two-ton-3d-printer/

#Innovation #TechRevolution #ThinkBigger #ChallengeTheNorm #Progress

When will we stop settling for mediocrity in innovation? A surplus industrial robot arm has been transformed into a two-ton 3D printer, and while some might call this creative recycling, it highlights a glaring issue in our approach to technology! Instead of pushing boundaries and investing in groundbreaking advancements, we’re simply repurposing outdated machinery!

Why must we wait for someone like Brian Brocken to show us the potential of what we already have? This is a clear sign that we need to embrace radical innovation, rather than just making do with what's left behind. We should be demanding more from ourselves and from our tech!

Let’s not accept the status quo – let’s strive for true progress. Are you ready to challenge the norm and think bigger?

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/19/surplus-industrial-robot-becomes-two-ton-3d-printer/

#Innovation #TechRevolution #ThinkBigger #ChallengeTheNorm #Progress

0 Commenti

·0 condivisioni