NASA says Orions heat shield is good to go for Artemis IIbut does it matter?

arstechnica.com

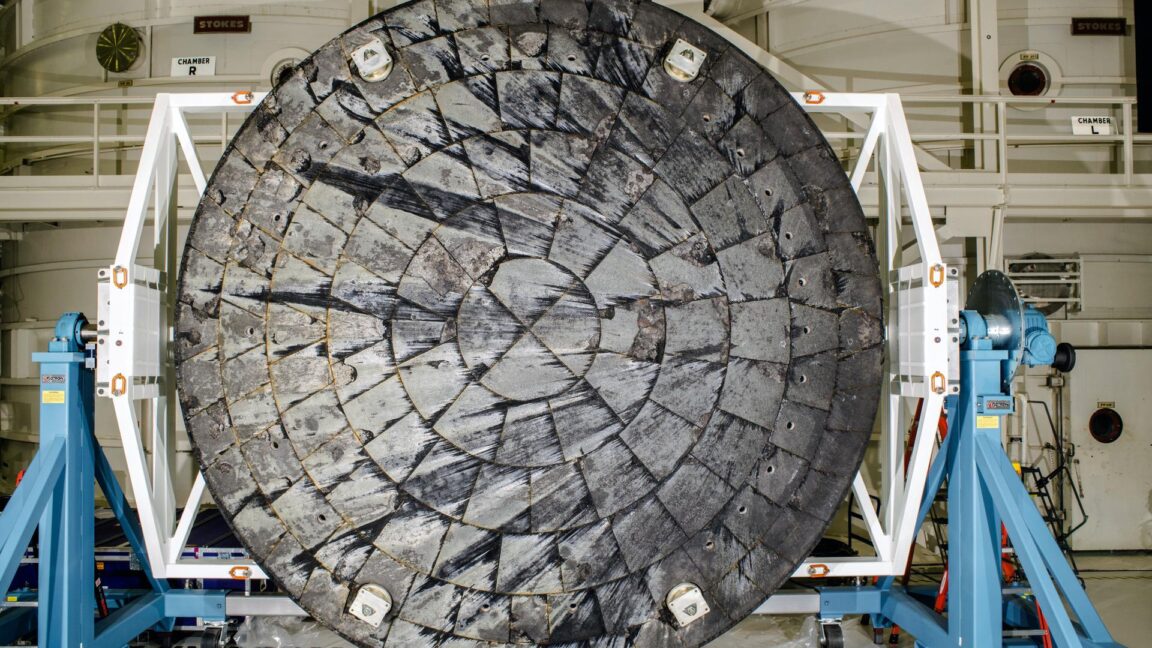

What is time? NASA says Orions heat shield is good to go for Artemis IIbut does it matter? The Artemis II mission, as NASA currently envisions it, won't launch until April 2026. Stephen Clark Dec 5, 2024 8:03 pm | 0 The heat shield from the Artemis I mission, showing evidence of cracks and missing Avcoat material. Credit: NASA The heat shield from the Artemis I mission, showing evidence of cracks and missing Avcoat material. Credit: NASA Story textSizeSmallStandardLargeWidth *StandardWideLinksStandardOrange* Subscribers only Learn moreTwo years ago next week, NASA's Orion spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to wrap up what, at first glance, seemed to be a highly successful unpiloted test flight that made a return to the Moon feel within reach.The Orion capsule descended under parachutes, right on target near a US Navy recovery ship on December 11, 2022. In 25-and-a-half days, the Orion spacecraft entered the Moon's sphere of influence, flew within about 60 miles (100 kilometers) of the lunar surface, and, for the most part, worked as designed in deep space. On top of that, the rocket's launch vehicle, NASA's heavy-lift Space Launch System, also performed near-flawlessly on its first flight, known as Artemis I.However, once NASA engineers got a closer look at the Orion spacecraft, their optimism faded. They saw cracks in the craft's heat shield and divots in the ablative thermal protection layer resembling potholes on a neglected street. This isn't what engineers expected, and they spent the next two years investigating the cause of the problem and determining whether it posed a safety risk for NASA's next Artemis mission, Artemis II. If the results weren't favorable, NASA might have to disassemble the Orion spacecraft, pushing back the flight a year or more beyond the Artemis II mission's already-delayed launch date.On NASA's roadmap to land astronauts on the Moon, Artemis II is the first mission that will put astronauts at the controls of the Orion spacecraft. Finally, agency officials announced the results of the heat shield inquiry Thursday. The conclusion among NASA's engineering team is to fly the Artemis II mission as intended, with a team of four astronauts on a circumlunar free return trajectory, taking them from Earth beyond the far side of the Moon, and then back home for a high-speed reentry and splashdown in the Pacific."Based on the data, we have decidedNASA unanimously and our decision-makersto move forward with the current Artemis II Orion capsule and heat shield, with a modified entry trajectory," said Bill Nelson, NASA's administrator. "Additionally, we need to complete our updates to the Orion environmental controls and life support systems that were identified earlier this year."NASA said the heat shield investigation and other issues with the Orion spacecraft have delayed the Artemis II launch until April 2026, a slip of seven months from the previous launch date in September 2025. The Artemis III mission, slated to be the Artemis program's first crewed lunar landing at the Moon's south pole, won't fly before mid-2027, about a year later than NASA's previous schedule.This follows NASA's announcement last January that Artemis II would miss its then-scheduled launch date in September of this year. Therefore, in less than 11 months, Artemis II's official launch date has slipped by 19 months.The root of the problemComing back from the Moon, the Orion spacecraft reenters the atmosphere traveling 32 times the speed of sound, about 30 percent faster than a spacecraft returning from low-Earth orbit. At this velocity, Orion encounters temperatures of up to 5,000 Fahrenheit (2,760 Celsius).The heat shield, made of a material called Avcoat, is attached to the base of the Orion spacecraft in 186 blocks. A char layer that builds up on the outer skin of the Avcoat material is supposed to ablate, or erode, in a predictable manner during reentry. Instead, fragments fell off the heat shield and left cavities in the Avcoat material at the end of the Artemis I mission.Substantial testing in ground facilities, including in wind tunnels and high-temperature arc jet chambers, allowed engineers to find the root cause.Orion flew a skip reentry profile during Artemis I, when it dipped into the atmosphere, skipped back into space, and then made a final descent into the atmosphere, sort of like a rock skipping across a pond. This profile allows Orion to fly longer distances downrange to target splashdowns near recovery teams in the Pacific Ocean and reduces g-forces on the spacecraft and the crew riding inside. It also splits up the heat load on the spacecraft into two phases."We have since determined that while the capsule was dipping in and out of the atmosphere, as part of that planned skip entry, heat accumulated inside the heat shield outer layer, leading to gases forming and becoming trapped inside the heat shield," said Pam Melroy, NASA's deputy administrator. "This caused internal pressure to build up and led to cracking and uneven shedding of that outer layer."An independent team of experts concurred with NASA's determination of the root cause, Melroy said. NASA administrator Bill Nelson, deputy administrator Pam Melroy, associate administrator Jim Free, and Artemis II commander Reid Wiseman speak with reporters Thursday in Washington, DC. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls Counterintuitively, this means NASA engineers are comfortable with the safety of the heat shield if the Orion spacecraft reenters the atmosphere at a slightly steeper angle than it did on Artemis I and spends more time subjected to higher temperatures.When the Orion spacecraft climbed back out of the atmosphere during the Artemis I skip reentry, a period known as the skip dwell, NASA said heating rates decreased and thermal energy accumulated inside the heat shields Avcoat material. This generated gases inside the heat shield through a process knownas pyrolysis."Pyrolysis is just burning without oxygen," said Amit Kshatriya, deputy associate administrator of NASA's Moon to Mars program. "We learned that as part of that reaction, the permeability of the Avcoat material is essential."During the skip dwell, "the production of those gases was higher than the permeability could tolerate, so as a result, pressure differential was created. That pressure led to cracks in plane with the outer mold line of the vehicle," Kshatriya said.NASA didn't know this could happen because engineers tested the heat shield on the ground at higher temperatures than the Orion spacecraft encountered in flight to prove the thermal barrier could withstand the most extreme possible heating during reentry."What we missed was this critical region in the middle, and we missed that region because we didn't have the test facilities to produce the low-level energies that occur during skip and dwell," Kshatriya said Thursday.During the investigation, NASA replicated the charring and cracking after engineers devised a test procedure to expose Avcoat heat shield material to the actual conditions of the Artemis I reentry.So, for Artemis II, NASA plans to modify the reentry trajectory to reduce the skip reentry's dwell time. Let's include some numbers to help illustrate the difference.The distance traveled by Artemis I during the reentry phase of the mission was more than 3,000 nautical miles (3,452 miles; 5,556 kilometers), according to Kshatriya. This downrange distance will be limited to no more than 1,775 nautical miles (2,042 miles; 3,287 kilometers) on Artemis II, effectively reducing the dwell time the Orion spacecraft spends in the lower heating regime that led to the cracking on Artemis I. NASA's inspector general report in May included new images of Orion's heat shield that the agency did not initially release after the Artemis I mission. Credit: NASA Inspector General With this change, Kshatriya said NASA engineers don't expect to see the heat shield erosion they saw on Artemis I. "The gas generation that occurs during that skip dwell is sufficiently low that the environment for crack generation is not going to overwhelm the structural integrity of the char layer."For future Orion spaceships, NASA and its Orion prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, will incorporate changes to address the heat shield's permeability problem.Waiting for what?NASA officials discussed the heat shield issue, and broader plans for the Artemis program, in a press conference in Washington on Thursday. But the event's timing added a coat of incredulity to much of what they said. President-elect Donald Trump, with SpaceX founder Elon Musk in his ear, has vowed to cut wasteful government spending.While that means there is a good chance for a change in how the US will return astronauts to the Moon, it doesn't necessarily imply a change in the what or why. Trump's association with Musk, Nelson said Thursday, is a good thing for the US space program.I am an optimist by nature, but in this particular case, I think that the relationship between Elon Musk and the president-elect is going to be a benefit in making sure that the funding for NASA is there, so I see that as a positive," said Nelson, a former Democratic senator from Florida who counts himself as a friend of President Joe Biden. On Wednesday, Trump nominated billionaire businessman, pilot, and private astronaut Jared Isaacman to replace Nelson as NASA's next administrator. Musk's influence and the selection of Isaacman to lead NASA suggest the space agency is about to undergo a significant strategic shift.This means an emphasis on speed and results, and there are widespread doubts NASA's current approach to the Artemis program can deliver either one. It's plausible, perhaps probable, that the Trump administration will attempt to cancel the Space Launch System rocket. NASA's inspector general reported the SLS rocket alone costs more than $2 billion to build and launch one time, a figure that doesn't include expenses on ground infrastructure or the Orion capsule it is supposed to boost into space. The Space Launch System rocket lifts off on the Artemis I mission. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls Ars has reported on how NASA might get to the Moon without the SLS rocket, potentially cobbling together commercial hardware from a range of companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and United Launch Alliance. This would not be a trivial undertaking, but it would get NASA out from under the more than $3 billion budget devoted to the SLS rocket and associated ground systems each year.The short-term future of the Orion program might be on a more stable footing. The heat shield problem aside, Orion is the only existing spacecraft with a fair chance of carrying people to the vicinity of the Moon within the next couple of years, enabling a US crew landing before China says it plans to do it in 2030. For the final leg of the journey to the Moon's south pole, NASA has contracts with SpaceX and Blue Origin to develop human-rated landers that will link up with the Orion capsule in lunar orbit.SpaceX's design is based on the company's powerful Starship rocket, which outclasses the SLS in terms of lift capacity and is designed for full reusability. SpaceX envisions Starship as a vehicle to transport more than 100 metric tons of cargo and people to the Moon and Mars, and eventually plans to certify it to launch and land on Earth with humans, a capability the rocket doesn't necessarily need to achieve NASA's initial goals with the Artemis program.While it won't be as impressive of a feat of landing astronauts on the Moon again, the Artemis II mission, as envisioned by NASA today, would be a notable achievement. Four astronauts, led by commander Reid Wiseman, are training for the Artemis II mission, and they will be the first people to fly near the Moon since the last Apollo mission in 1972. Their exact flight path will depend on the day they launch, but there's a chance Wiseman and his crewmates will travel farther from Earth than anyone in history.While Orion doesn't require the Space Launch System rocket, it does need a working heat shield. The spacecraft's reentry parameters won't change, regardless of which rocket the new NASA leadership chooses to launch Orion, so understanding the heat shield's performance remains an important matter."We have a large decision behind us," Wiseman said. "A lot of the uncertainty has been removed, and were wrapping things up on Orion."This may be true regarding the design of Orion's heat shield, but there's plenty of doubt about how the Trump administration might reshape the Artemis program come January.Stephen ClarkSpace ReporterStephen ClarkSpace Reporter Stephen Clark is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the worlds space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet. 0 Comments Prev story

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·113 Views