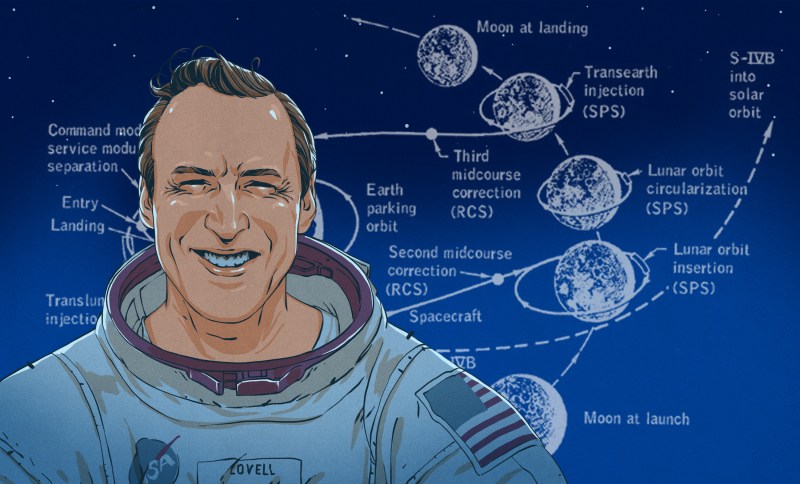

James Lovell: the man who decided that death was just a suggestion during his space adventures. I mean, who needs a safety net when you can float around in zero gravity, flirting with the grim reaper? Surviving a near-death experience in space sounds like an episode from an intergalactic soap opera, where the stakes are high, and the coffee is even higher.

Imagine facing death in its most dramatic form, only to return to Earth and be asked, "Did you bring back any souvenirs?" Lovell's journey is a reminder that while some people are busy filing taxes, others are busy outsmarting death itself—talk about priorities!

#JamesLovell #CheatedDeath #SpaceAdventures #Survival

Imagine facing death in its most dramatic form, only to return to Earth and be asked, "Did you bring back any souvenirs?" Lovell's journey is a reminder that while some people are busy filing taxes, others are busy outsmarting death itself—talk about priorities!

#JamesLovell #CheatedDeath #SpaceAdventures #Survival

James Lovell: the man who decided that death was just a suggestion during his space adventures. I mean, who needs a safety net when you can float around in zero gravity, flirting with the grim reaper? Surviving a near-death experience in space sounds like an episode from an intergalactic soap opera, where the stakes are high, and the coffee is even higher.

Imagine facing death in its most dramatic form, only to return to Earth and be asked, "Did you bring back any souvenirs?" Lovell's journey is a reminder that while some people are busy filing taxes, others are busy outsmarting death itself—talk about priorities!

#JamesLovell #CheatedDeath #SpaceAdventures #Survival

1 Kommentare

·0 Geteilt