Professional Honorary Organization

191 people like this

19 Posts

0 Photos

0 Videos

Share

Share this page

Visual Effects (VFX)

Recent Updates

-

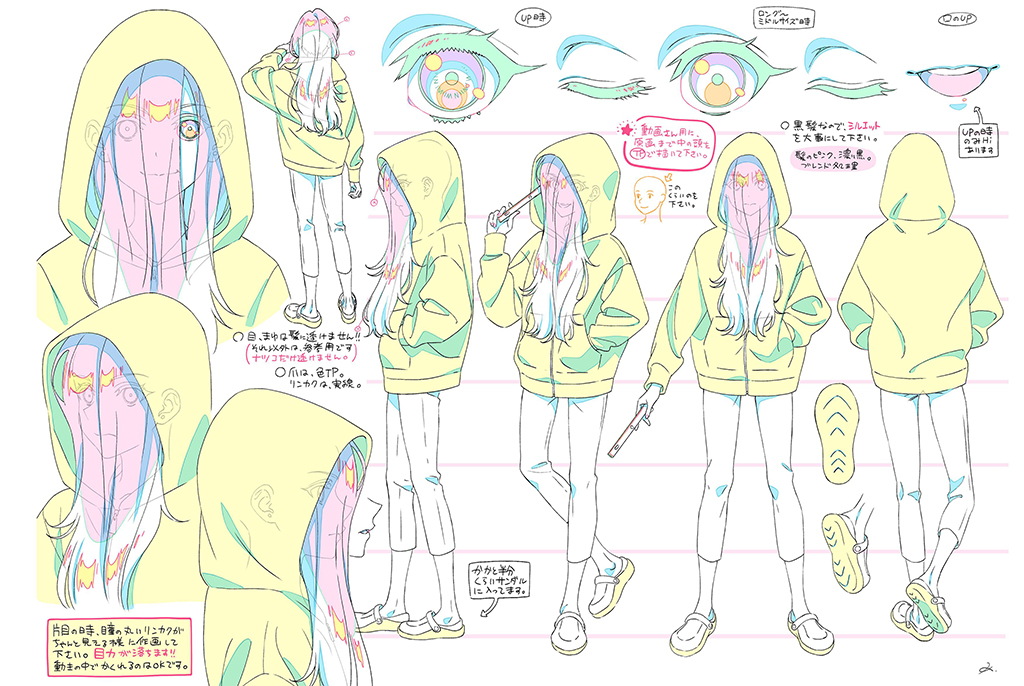

ZENSHU HONORS THE PAST AND FUTURE OF ANIMEvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of MAPPA.In most cases, an anime project is based on an original manga, but MAPPA decided to take a different approach from Chainsaw Man and Hells Paradise: Jigokuraku and come up with their own IP called Zenshu. The title translates to redo everything, which is a term often used in the anime industry, and is appropriate given that the story revolves around wunderkind animator and director Natsuko Hirose struggling to meet expectations and deadlines for her latest production, only to find herself becoming a character within her favorite movie A Tale of Perishing. The instrument of magic is not a wand or a sword but a peg bar used to keep animation drawings aligned, which allows the protagonist, Natsuko Hirose, to literally bring her illustrations to life. The Isekai series, streaming on Crunchyroll, consists of 12 episodes and was created by Mitsue Yamazaki and Kimiko Ueno. The original character designs were by Yoshiteru Tsujino and subsequently adapted for animation by Kayoko Ishikawa, who has previously worked on Saraznmai,Aikatsui! and Uchitama?! doing everything from storyboards, prop and costume design, color coordination and direction.Key attributes of Natsuko Hirose are her hoodie, long black hair and big blue eyes.[The animation style] also expresses the trials and struggles, the sincerity and joy experienced by the new generation of creators as they try to shape the future of animation; that spirit itself is reflected in the animation style. At its core, I believe these feelings are something that can resonate across different countries, eras, races and professions.Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer & Chief Animation DirectorSince we already had Tsujino-sans original character concept design, I didnt feel there was that much freedom in designing the characters, states Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer and Chief Animation Director of Zenshu. Yamazaki-san requested designs that would feel in line with todays anime style, so I aimed for a manga-like look that wouldnt come across as too realistic. Colors were part of the design process for both the costumes and characters. I felt my experience [as a costume and character designer] helped me when I was thinking of the balance between colors and individual design elements. Especially with Natsukos hair, since its very dark, long black hair. If you dont create gaps to it when its flowing in the wind, the silhouette becomes too heavy, and it makes it look like a big, heavy, black mass. Also, the highlights on the hair stand out, so if they are placed in an unnatural way, it immediately feels off to the viewer. I had not worked on a project that required this much care when handling black hair, so it was a great learning experience.The design of Luke Braveheart is based on the classic strait-laced hero found in old-school video games.Being a chief animation director influenced the approach towards the character design. Id say its all about striking a balance between the visual appeal and how easy the characters are for animators to draw, Ishikawa notes. I felt that finding the right mix of relatability and sophistication in a design is quite difficult. I dont want the designs to turn out self-indulgent, but with so many internal conflicts, its something I really struggle with. During weekly script meetings, Mitsue Yamazaki and Kimiko Ueno discussed the story and characters. I gradually started to get a sense of what Yamazaki-san and Ueno-san wanted to do, and what they liked. Each week, I would create image boards and character sketches, and wed keep adjusting and aligning our visions little by little.All of the character designs were created using Adobe Photoshop, Clip Studio Paint and a Wacom pen display tablet. I chose this style because it allows me to easily create and adjust variations in colors and details, Ishikawa remarks. I used the same approach in Zenshu as well; however, since we aimed for an analogue feel for the scenes where characters drawn by Natsuko appear, I drew the characters that appear on these scenes on paper with pencils.Exploring the moment when the peg bar becomes activated enabling Natsuko Hirose to turn her ability to illustrate into a superpower.Certain things need to be kept in mind when designing characters. I focus on capturing each characters unique personality as well as organizing the details for both close-ups and long shots, Ishikawa explains.By capturing characters personality, I mean drawing expressions and poses that convey the characters traits clearly. Organizing details means adjusting the amount of visual information on the screen so the workload of the many different artists doesnt become excessively difficult. And also preventing lines from clustering so much that the characters form becomes unclear. For close-up shots, the character fills the screen, so I add detailed elements to enhance the visual appeal. For long shots, I simplify the designs by omitting fine details.Mitsue Yamazaki wanted modern-looking designs. I explored and adopted a stylized character design that would appeal to people in their 20s and 30s, Ishikawa explains. I researched trending illustrations, films and animations. Since the world that the heroine enters resembles a medieval European fantasy world, I took inspiration from films like The Three Musketeers and The Lord of the Rings. The animation style honors the pioneers of animation. It also expresses the trials and struggles, the sincerity and joy experienced by the new generation of creators as they try to shape the future of animation; that spirit itself is reflected in the animation style. At its core, I believe these feelings are something that can resonate across different countries, eras, races and professions.The peg bar used by animators to ensure that their animation papers stay aligned when drawing takes on the magical qualities of a wand inside the fantasy world of A Tale of Perishing.The child, teen and adult designs of Natsuko Hirose were driven by her character arc. The current Natsuko has a strong sense of self and speaks in a direct manner, so her stance is confident, Ishikawa states. Hands on her hips, feet firmly apart. While shes earnest, she also has a playful side, which is why Ive actively incorporated comical and quirky poses and facial expressions. In her childhood, theres an unrevealed backstory. Natsuko was raised by a single mother who worked long hours as a nurse and didnt have much time to spend with her. Because of this, Natsuko matured faster than other kids and often wore hand-me-down clothes from neighbors. By junior high, with stricter teachers around, she started paying more attention to her appearance by cutting her hair neatly and wearing a headband, but her assertive personality only grew stronger. In high school, she found a clear goal and lived with a laser focus on the shortest path to achieve it. You can clearly see the evolution of her character by lining up her designs and comparing how shes portrayed at each stage of her life.Its all about striking a balance between the visual appeal and how easy the characters are for animators to draw. I felt that finding the right mix of relatability and sophistication in a design is quite difficult. I dont want the designs to turn out self-indulgent, but with so many internal conflicts, its something I really struggle with.Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer & Chief Animation DirectorDetermining the directionality and shot design of a stopwatch, animation paper and drawing pencil swirling around in a fanciful manner.Often obscuring the entire face of Natsuko Hirose is her long black hair, which is character in its own right. I was taught that when people look at someone, the first thing they focus on is the eyes, Ishikawa remarks. So, I wondered how we can convey the characters emotions to the audience when the eyes are completely or almost completely hidden. Even if only one eye is visible, if the pupil is even slightly hidden, the emotions become difficult to read. I made guidelines for creating the animation. The pupils must never be completely hidden. Its okay if hair falls over them when the character is moving! Another guideline I had was that emotions should be conveyed through exaggerated reactions. At first, the audience was clearly confused because they couldnt read emotions from her face and therefore didnt understand what kind of a character Natsuko was. But that actually mirrored Natsukos own state; her attempt to hide her true feelings. As she gradually opened up, she transformed her bangs into a palm tree, put her hair up in a bun and hid her face again when she started feeling down. Natsukos hair turned out to be more expressive than I had imagined. Its rare to see a character whose hair carries so much emotional weight.A chair appears that propels Natsuko Hirose towards a desk where all of the required tools to animate are culminating.Audience members have preconceived notions as to what unicorns, dragons and elves should look like despite never ever actually seeing one in real life. Im used to drawing ordinary humans, but when it comes to animals or dragons, I find them harder to draw, Ishikawa admits. Since many animators will be involved in drawing these characters, I aimed to make them easier to animate by giving them human-like proportions and clothing, and by keeping the designs simple while still aiming to create characters with the kind of cuteness that Tsujino-sans characters have. Justice is the former dragon member of the Nine Soldiers who has been grounded by a damaged wing and has become a drunk. Since the character is androgynous, I was careful not to lean too much toward either masculinity or femininity in the design. Justice has an exclusive, slightly melancholic kind of sexiness, but they also have an earnest personality and are loyal to their friends, so I tried to capture that contrast in their gestures and expressions. This was the most challenging character to work on. It took me a long time to grasp the three-dimensional structure of Justice and figure out how best to draw them.Luke Braveheart is the tragic male lead of A Tale of Perishing and the first love of Natsuko Hirose. The design of Luke Braveheart is based on the classic strait-laced hero that Tsujino-san drew, one that youd see in an old-school video game, Ishikawa states. He stands tall and serious with a strong and dignified presence. At the same time, Luke also has age-appropriate cuteness and sexiness that shows in the way he panics and fumbles after suddenly falling in love for the first time. I included little details like loose strands of hair, well-defined muscles and a smile thats both cute and cool. I also gave him expressions that would make Natsukos heart skip a beat. Memmelin is the Elven member of the Nine Soldiers. Although she looks like a child, shes actually the oldest member of the group, Ishikawa observes. Thats why her stance and facial expressions have a calm, mature confidence. For the Harvest Festival, she wears a sexy, grown-up mermaid-line dress. But, in the dance scene with the Ultimate Exister, they wear a floral dress covered in frills, the kind of outfit Memmelin probably dreams of wearing but would be too shy to choose herself.Conceptualizing the moment when Natsuko Hirose sits at her desk and creates illustrations that literally come to life.Key animation sketch of the unicorn character of Unio paired with a final still, which has a stuffed toy aesthetic.A highly-stylized approach was adopted for Memmelins unicorn colleague Unio. Tsujino-sans design was already great, so I pretty much kept it as it was. Yamazaki-san wanted the joints to be soft and floppy like a stuffed animal, so I made them soft and floppy. I also wanted to add unicorns fanciful charm, so when he runs through the sky a rainbow appears and when we zoom in on his eyes, you can see sparkling rainbow reflections. The robot design for QJ remained close to the original one as well. Since I wanted him to have a bit more of a mascot-like feel, I made him look slightly cuter. For the Harvest Festival, his outfit is inspired by Jomon-period clothing decorated with natural stones and ropes for a dressed-up, festive look.Planning out what would become a signature image for the series.Sketching and animating the emotional turmoil that threatens to engulf Luke Braveheart.Memmelin finds herself falling in love with Ultimate Exister, who is one of the living illustrations created by Natsuko Hirose.Treated as character as in its own right is the long black hair of Natsuko Hirose that often obscures her face.Although Memmelin looks like a child, she is actually the oldest member of the group, which is why her stance and facial expressions have a calm, mature confidence.The robot design for QJ remained close to the original, which gave him a mascot look.Often hidden behind the long black hair are the big beautiful blue eyes of Natsuko Hirose.Going through a major physical transformation is Destiny Heartwarming, the daughter of the mayor of The Last Town. I built on Tsujino-sans original concept adding plump curves, pouty lips and big, droopy eyes, Ishikawa describes. I packed her to the brim with both cuteness and sexiness. For the muscular version, I wanted it to also have grace, so I aimed for something between a bodybuilder and a pro wrestler. Even with all the muscles, her pose keeps a distinctly feminine touch. The heroine of Zenshu went through the most iterations. Natsuko originally had short hair, but partway through the project, both the story and her character took a major turn; she turned into a Natsuko straight out of Japanese horror. The design with long hair covering her face added a sense of mystery, not only deepening her character, but also expanding the range of the story. Both her personality and appearance ended up with a much greater variety. A significant aspect in finding the correct character design involves adjusting facial features and trying different color variations. Its sometimes hard to keep working when nothing feels quite right, but when everything finally comes together and I get the feeling of This is it! I feel joy that nothing else can compare to. I also really enjoyed working on the many comical characters.0 Comments ·0 SharesPlease log in to like, share and comment!

ZENSHU HONORS THE PAST AND FUTURE OF ANIMEvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of MAPPA.In most cases, an anime project is based on an original manga, but MAPPA decided to take a different approach from Chainsaw Man and Hells Paradise: Jigokuraku and come up with their own IP called Zenshu. The title translates to redo everything, which is a term often used in the anime industry, and is appropriate given that the story revolves around wunderkind animator and director Natsuko Hirose struggling to meet expectations and deadlines for her latest production, only to find herself becoming a character within her favorite movie A Tale of Perishing. The instrument of magic is not a wand or a sword but a peg bar used to keep animation drawings aligned, which allows the protagonist, Natsuko Hirose, to literally bring her illustrations to life. The Isekai series, streaming on Crunchyroll, consists of 12 episodes and was created by Mitsue Yamazaki and Kimiko Ueno. The original character designs were by Yoshiteru Tsujino and subsequently adapted for animation by Kayoko Ishikawa, who has previously worked on Saraznmai,Aikatsui! and Uchitama?! doing everything from storyboards, prop and costume design, color coordination and direction.Key attributes of Natsuko Hirose are her hoodie, long black hair and big blue eyes.[The animation style] also expresses the trials and struggles, the sincerity and joy experienced by the new generation of creators as they try to shape the future of animation; that spirit itself is reflected in the animation style. At its core, I believe these feelings are something that can resonate across different countries, eras, races and professions.Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer & Chief Animation DirectorSince we already had Tsujino-sans original character concept design, I didnt feel there was that much freedom in designing the characters, states Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer and Chief Animation Director of Zenshu. Yamazaki-san requested designs that would feel in line with todays anime style, so I aimed for a manga-like look that wouldnt come across as too realistic. Colors were part of the design process for both the costumes and characters. I felt my experience [as a costume and character designer] helped me when I was thinking of the balance between colors and individual design elements. Especially with Natsukos hair, since its very dark, long black hair. If you dont create gaps to it when its flowing in the wind, the silhouette becomes too heavy, and it makes it look like a big, heavy, black mass. Also, the highlights on the hair stand out, so if they are placed in an unnatural way, it immediately feels off to the viewer. I had not worked on a project that required this much care when handling black hair, so it was a great learning experience.The design of Luke Braveheart is based on the classic strait-laced hero found in old-school video games.Being a chief animation director influenced the approach towards the character design. Id say its all about striking a balance between the visual appeal and how easy the characters are for animators to draw, Ishikawa notes. I felt that finding the right mix of relatability and sophistication in a design is quite difficult. I dont want the designs to turn out self-indulgent, but with so many internal conflicts, its something I really struggle with. During weekly script meetings, Mitsue Yamazaki and Kimiko Ueno discussed the story and characters. I gradually started to get a sense of what Yamazaki-san and Ueno-san wanted to do, and what they liked. Each week, I would create image boards and character sketches, and wed keep adjusting and aligning our visions little by little.All of the character designs were created using Adobe Photoshop, Clip Studio Paint and a Wacom pen display tablet. I chose this style because it allows me to easily create and adjust variations in colors and details, Ishikawa remarks. I used the same approach in Zenshu as well; however, since we aimed for an analogue feel for the scenes where characters drawn by Natsuko appear, I drew the characters that appear on these scenes on paper with pencils.Exploring the moment when the peg bar becomes activated enabling Natsuko Hirose to turn her ability to illustrate into a superpower.Certain things need to be kept in mind when designing characters. I focus on capturing each characters unique personality as well as organizing the details for both close-ups and long shots, Ishikawa explains.By capturing characters personality, I mean drawing expressions and poses that convey the characters traits clearly. Organizing details means adjusting the amount of visual information on the screen so the workload of the many different artists doesnt become excessively difficult. And also preventing lines from clustering so much that the characters form becomes unclear. For close-up shots, the character fills the screen, so I add detailed elements to enhance the visual appeal. For long shots, I simplify the designs by omitting fine details.Mitsue Yamazaki wanted modern-looking designs. I explored and adopted a stylized character design that would appeal to people in their 20s and 30s, Ishikawa explains. I researched trending illustrations, films and animations. Since the world that the heroine enters resembles a medieval European fantasy world, I took inspiration from films like The Three Musketeers and The Lord of the Rings. The animation style honors the pioneers of animation. It also expresses the trials and struggles, the sincerity and joy experienced by the new generation of creators as they try to shape the future of animation; that spirit itself is reflected in the animation style. At its core, I believe these feelings are something that can resonate across different countries, eras, races and professions.The peg bar used by animators to ensure that their animation papers stay aligned when drawing takes on the magical qualities of a wand inside the fantasy world of A Tale of Perishing.The child, teen and adult designs of Natsuko Hirose were driven by her character arc. The current Natsuko has a strong sense of self and speaks in a direct manner, so her stance is confident, Ishikawa states. Hands on her hips, feet firmly apart. While shes earnest, she also has a playful side, which is why Ive actively incorporated comical and quirky poses and facial expressions. In her childhood, theres an unrevealed backstory. Natsuko was raised by a single mother who worked long hours as a nurse and didnt have much time to spend with her. Because of this, Natsuko matured faster than other kids and often wore hand-me-down clothes from neighbors. By junior high, with stricter teachers around, she started paying more attention to her appearance by cutting her hair neatly and wearing a headband, but her assertive personality only grew stronger. In high school, she found a clear goal and lived with a laser focus on the shortest path to achieve it. You can clearly see the evolution of her character by lining up her designs and comparing how shes portrayed at each stage of her life.Its all about striking a balance between the visual appeal and how easy the characters are for animators to draw. I felt that finding the right mix of relatability and sophistication in a design is quite difficult. I dont want the designs to turn out self-indulgent, but with so many internal conflicts, its something I really struggle with.Kayoko Ishikawa, Character Designer & Chief Animation DirectorDetermining the directionality and shot design of a stopwatch, animation paper and drawing pencil swirling around in a fanciful manner.Often obscuring the entire face of Natsuko Hirose is her long black hair, which is character in its own right. I was taught that when people look at someone, the first thing they focus on is the eyes, Ishikawa remarks. So, I wondered how we can convey the characters emotions to the audience when the eyes are completely or almost completely hidden. Even if only one eye is visible, if the pupil is even slightly hidden, the emotions become difficult to read. I made guidelines for creating the animation. The pupils must never be completely hidden. Its okay if hair falls over them when the character is moving! Another guideline I had was that emotions should be conveyed through exaggerated reactions. At first, the audience was clearly confused because they couldnt read emotions from her face and therefore didnt understand what kind of a character Natsuko was. But that actually mirrored Natsukos own state; her attempt to hide her true feelings. As she gradually opened up, she transformed her bangs into a palm tree, put her hair up in a bun and hid her face again when she started feeling down. Natsukos hair turned out to be more expressive than I had imagined. Its rare to see a character whose hair carries so much emotional weight.A chair appears that propels Natsuko Hirose towards a desk where all of the required tools to animate are culminating.Audience members have preconceived notions as to what unicorns, dragons and elves should look like despite never ever actually seeing one in real life. Im used to drawing ordinary humans, but when it comes to animals or dragons, I find them harder to draw, Ishikawa admits. Since many animators will be involved in drawing these characters, I aimed to make them easier to animate by giving them human-like proportions and clothing, and by keeping the designs simple while still aiming to create characters with the kind of cuteness that Tsujino-sans characters have. Justice is the former dragon member of the Nine Soldiers who has been grounded by a damaged wing and has become a drunk. Since the character is androgynous, I was careful not to lean too much toward either masculinity or femininity in the design. Justice has an exclusive, slightly melancholic kind of sexiness, but they also have an earnest personality and are loyal to their friends, so I tried to capture that contrast in their gestures and expressions. This was the most challenging character to work on. It took me a long time to grasp the three-dimensional structure of Justice and figure out how best to draw them.Luke Braveheart is the tragic male lead of A Tale of Perishing and the first love of Natsuko Hirose. The design of Luke Braveheart is based on the classic strait-laced hero that Tsujino-san drew, one that youd see in an old-school video game, Ishikawa states. He stands tall and serious with a strong and dignified presence. At the same time, Luke also has age-appropriate cuteness and sexiness that shows in the way he panics and fumbles after suddenly falling in love for the first time. I included little details like loose strands of hair, well-defined muscles and a smile thats both cute and cool. I also gave him expressions that would make Natsukos heart skip a beat. Memmelin is the Elven member of the Nine Soldiers. Although she looks like a child, shes actually the oldest member of the group, Ishikawa observes. Thats why her stance and facial expressions have a calm, mature confidence. For the Harvest Festival, she wears a sexy, grown-up mermaid-line dress. But, in the dance scene with the Ultimate Exister, they wear a floral dress covered in frills, the kind of outfit Memmelin probably dreams of wearing but would be too shy to choose herself.Conceptualizing the moment when Natsuko Hirose sits at her desk and creates illustrations that literally come to life.Key animation sketch of the unicorn character of Unio paired with a final still, which has a stuffed toy aesthetic.A highly-stylized approach was adopted for Memmelins unicorn colleague Unio. Tsujino-sans design was already great, so I pretty much kept it as it was. Yamazaki-san wanted the joints to be soft and floppy like a stuffed animal, so I made them soft and floppy. I also wanted to add unicorns fanciful charm, so when he runs through the sky a rainbow appears and when we zoom in on his eyes, you can see sparkling rainbow reflections. The robot design for QJ remained close to the original one as well. Since I wanted him to have a bit more of a mascot-like feel, I made him look slightly cuter. For the Harvest Festival, his outfit is inspired by Jomon-period clothing decorated with natural stones and ropes for a dressed-up, festive look.Planning out what would become a signature image for the series.Sketching and animating the emotional turmoil that threatens to engulf Luke Braveheart.Memmelin finds herself falling in love with Ultimate Exister, who is one of the living illustrations created by Natsuko Hirose.Treated as character as in its own right is the long black hair of Natsuko Hirose that often obscures her face.Although Memmelin looks like a child, she is actually the oldest member of the group, which is why her stance and facial expressions have a calm, mature confidence.The robot design for QJ remained close to the original, which gave him a mascot look.Often hidden behind the long black hair are the big beautiful blue eyes of Natsuko Hirose.Going through a major physical transformation is Destiny Heartwarming, the daughter of the mayor of The Last Town. I built on Tsujino-sans original concept adding plump curves, pouty lips and big, droopy eyes, Ishikawa describes. I packed her to the brim with both cuteness and sexiness. For the muscular version, I wanted it to also have grace, so I aimed for something between a bodybuilder and a pro wrestler. Even with all the muscles, her pose keeps a distinctly feminine touch. The heroine of Zenshu went through the most iterations. Natsuko originally had short hair, but partway through the project, both the story and her character took a major turn; she turned into a Natsuko straight out of Japanese horror. The design with long hair covering her face added a sense of mystery, not only deepening her character, but also expanding the range of the story. Both her personality and appearance ended up with a much greater variety. A significant aspect in finding the correct character design involves adjusting facial features and trying different color variations. Its sometimes hard to keep working when nothing feels quite right, but when everything finally comes together and I get the feeling of This is it! I feel joy that nothing else can compare to. I also really enjoyed working on the many comical characters.0 Comments ·0 SharesPlease log in to like, share and comment! -

DIGITAL DOMAIN DELIVERS THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS FOR THE CONJURING: LAST RITESvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of Digital Domain and Warner Bros. Pictures.Bringing the paranormal investigative stories of the Ed and Lorraine Warren full circle is the haunting that started everything reemerging in The Conjuring: Last Rites under the direction of Michael Chaves and starring Vera Farmiga, Patrick Wilson, Mia Thomlinson and Ben Hardy. Brought on to heighten the supernatural horror was Scott Edelstein, who served as Production Visual Effects Supervisor and hired his colleagues at Digital Domain to create 425 shots that feature making the 12-foot tall Annabelle doll, crafting a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold, producing the haunted Conjuring Mirror, destroying a hallway, and recreating the small mill-town setting. I know Scott, so in that sense it made things a lot easier and more comfortable from the get-go because you know who youre talking to and how to interpret the things he says, Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor at Digital Domain. The first step was to try to not get scared watching the previous movies and absorb as much of that look, aesthetic and atmosphere, and to respect that in the new movie. An effort was made to upgrade effects while also honoring what had already been established. Were choosing to do it in 3D for this movie, and theres a lot of things that dont work anymore. But we found that we were able to recreate the 2D look with our 3D approach.Conveying a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold was a fine line between being creepy or silly.The first step was to try to not get scared watching the previous movies and absorb as much of that look, aesthetic and atmosphere, and to respect that in the new movie.Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor, Digital DomainRaising the level of difficulty for the environment work was a long oner. There was one plate in the street with the character coming out of the car. The camera zooms out and starts to fly above the house, looks around in the street, then comes back down, bursts through the door, and once we get into the house, we get into the next plate photography of the actress in there, Millet explains. The way we decided to work with this was to rebuild the entire street in CG because we found that was easier for us than trying to transition the plate street with our street and having to have every single detail of the street perfectly match one-to-one. We kept the car and character from the plate. As the camera pulls back, we transition toward the CG car and the digital double of the actor. Then were into a full CG version of the shot. We go up to the house, and most of the street is actually 3D because everything needed to work with parallax. Only the far background extension was a matte painting. Then we crash down. Were still full CG. We have rain and atmosphere. All of that is CG. We crash through the door, and once the door opens, we have a few frames of CG inside the house to help us with the transition. After that, were back to the plate.The supernatural aspect of the Annabelle doll becoming 12 feet tall gave Digital Domain the freedom to do whatever looked best without necessarily having to be confined to reality.Going into the realm of the supernatural and hallucinations is the appearance of 12-foot-tall version of the Annabelle doll. Theres a lot of things we started to think about like, what does the dress look like when its 12 feet tall? Is it a much thicker material? Do the wrinkles work differently because the material is that big, or is the material the same thickness but way bigger and looks like a curtain? The supernatural aspect of it gave us the freedom to do whatever we thought looked best without necessarily having to be like, This is what it would be like if you build a dress that was 12 feet tall, and it might not look super great, but thats actually how it would work and react. We didnt have to worry too much about that, and we were able to do what everyone thought was the best look. The transformation went through several iterations. The director wanted the doll to read as if the transformation was a painful process that evolved across the shots. He worked with the postvis department to figure out the timing, and then we took over. Once the animation started, we added that chunkiness you see in the growth.The hallway was modeled with the destruction in mind.Conveying a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold was a fine line between being creepy or silly. We did a bunch of iterations to find the smile that worked the best, Millet remarks. We had some versions where it was definitely not creepy. It would make you laugh as soon as you see it. It was a combination of not just the mouth, but the look in the eyes and the way all of the little muscles in the face move. Everyone is an expert because we all look at faces every day, so its a much less forgiving thing to do than pretty much any other aspect of what we do in visual effects. Michael Chaves did concept art to illustrate what he wanted. That was incredibly helpful, because we had an exact target to match. The goal for us was to try to match his concept and give it life. The smile was exaggerated then rolled back. We did a bunch of iterations with a different range and smile, but all going much further than what we knew was needed. That helped us not to baby-step the process because the last thing you want is, Oh, a little bit more. And you spend weeks doing that. We went way out in terms of how wide that smile was and showed all of those versions. Once the director was happy with one of them, we actually selected a range to give us an idea of what to work within, and then we made that range as good as we could.[Director Michael Chaves concept art] was incredibly helpful, because we had an exact target to match. The goal for us was to try to match his concept and give it life.Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor, Digital DomainA signature terrifying prop for the franchise is the Conjuring Mirror.A signature terrifying prop for the franchise is the Conjuring Mirror. The work for us was adding the crack in the mirror throughout a lot of different sequences in the movie, Millet explains. First, it was establishing the look of that crack and getting it to read the same across the various shots. The thing with the crack was that in some shots, its going to look awesome and perfect, but in a different lighting condition you dont get the same highlights and, incidentally, the shape feels different even though its the same. The sequence in the hallway was a whole different thing. We had to completely rebuild the mirror in CG so we could animate it. On set, they tried to avoid any reflection problems, but with a big mirror you cant avoid it. There were a bunch of shots where we had to get rid of reflections showing the part of the set that wasnt built or crew members or a giant camera rig. The work for us was to rebuild the entire hallway CG so we could take over any reflection and rebuild any reflection that we needed to do. The hallway gets destroyed. We built the entire hallway then animated the CG mirror. Something we didnt expect was the mirror on set was shorter than the actual mirror we needed to build, so getting the mirror to reach everywhere in the walls was a fun challenge for animation and effects. Once that was figured out, we added some extra geometry behind the walls and under the floor because when we destroy everything, we will see stuff there. Then we moved forward with our effects destruction, so there were different layers of drywall, studs, installation and smoke. That was cool.The factory had to be seen in every shot that takes place in the mill town.A LEGO approach was adopted when constructing the various houses that populate a neighborhood.Set dressing, like wet asphalt and lights in the distance, provided the desired scope and mood for the nighttime shots.Practical houses were constructed, which helped ground the digital extensions.The crack in the Conjuring Mirror had to appear as if there was no point of impact.The Conjuring franchise is based on the exploits of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren, portrayed by Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga.Construction of the small mill town was tackled as if it was a LEGO set. We wanted to build a house in such a way that floors, colors and roofs could be easily changed, Millet remarks. A lot of our houses were built in three layers: ground floor, first floor and roof. The houses were built in a modular way so we could quickly populate the street, create a layout, and show something that gives you a feel for the street versus iterating on different houses. Geography had to be kept in mind to avoid discontinuity. When the characters drive on the bridge we needed to make sure that it feels like theyre going in the right direction. We had to have the factory looming above the town at all times, so it had to be in such a place that we would always see it when were at street level and in those shots where we go up a little bit. The set dressing can be unlimited. We had birds, cars, every plant has wind in it, and digital people looking around. There are lot of things going on, and as soon as you have to do that, it immediately gets rid of any 2D or matte painting approach. You have to build and animate it. But we also didnt want to take away from the action in the plate. Millet concludes, Overall, this was a small project, but ambitious with the work that had to be done within the given timeline. It was a great project to work on, and the challenges were interesting.0 Comments ·0 Shares

DIGITAL DOMAIN DELIVERS THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS FOR THE CONJURING: LAST RITESvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of Digital Domain and Warner Bros. Pictures.Bringing the paranormal investigative stories of the Ed and Lorraine Warren full circle is the haunting that started everything reemerging in The Conjuring: Last Rites under the direction of Michael Chaves and starring Vera Farmiga, Patrick Wilson, Mia Thomlinson and Ben Hardy. Brought on to heighten the supernatural horror was Scott Edelstein, who served as Production Visual Effects Supervisor and hired his colleagues at Digital Domain to create 425 shots that feature making the 12-foot tall Annabelle doll, crafting a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold, producing the haunted Conjuring Mirror, destroying a hallway, and recreating the small mill-town setting. I know Scott, so in that sense it made things a lot easier and more comfortable from the get-go because you know who youre talking to and how to interpret the things he says, Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor at Digital Domain. The first step was to try to not get scared watching the previous movies and absorb as much of that look, aesthetic and atmosphere, and to respect that in the new movie. An effort was made to upgrade effects while also honoring what had already been established. Were choosing to do it in 3D for this movie, and theres a lot of things that dont work anymore. But we found that we were able to recreate the 2D look with our 3D approach.Conveying a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold was a fine line between being creepy or silly.The first step was to try to not get scared watching the previous movies and absorb as much of that look, aesthetic and atmosphere, and to respect that in the new movie.Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor, Digital DomainRaising the level of difficulty for the environment work was a long oner. There was one plate in the street with the character coming out of the car. The camera zooms out and starts to fly above the house, looks around in the street, then comes back down, bursts through the door, and once we get into the house, we get into the next plate photography of the actress in there, Millet explains. The way we decided to work with this was to rebuild the entire street in CG because we found that was easier for us than trying to transition the plate street with our street and having to have every single detail of the street perfectly match one-to-one. We kept the car and character from the plate. As the camera pulls back, we transition toward the CG car and the digital double of the actor. Then were into a full CG version of the shot. We go up to the house, and most of the street is actually 3D because everything needed to work with parallax. Only the far background extension was a matte painting. Then we crash down. Were still full CG. We have rain and atmosphere. All of that is CG. We crash through the door, and once the door opens, we have a few frames of CG inside the house to help us with the transition. After that, were back to the plate.The supernatural aspect of the Annabelle doll becoming 12 feet tall gave Digital Domain the freedom to do whatever looked best without necessarily having to be confined to reality.Going into the realm of the supernatural and hallucinations is the appearance of 12-foot-tall version of the Annabelle doll. Theres a lot of things we started to think about like, what does the dress look like when its 12 feet tall? Is it a much thicker material? Do the wrinkles work differently because the material is that big, or is the material the same thickness but way bigger and looks like a curtain? The supernatural aspect of it gave us the freedom to do whatever we thought looked best without necessarily having to be like, This is what it would be like if you build a dress that was 12 feet tall, and it might not look super great, but thats actually how it would work and react. We didnt have to worry too much about that, and we were able to do what everyone thought was the best look. The transformation went through several iterations. The director wanted the doll to read as if the transformation was a painful process that evolved across the shots. He worked with the postvis department to figure out the timing, and then we took over. Once the animation started, we added that chunkiness you see in the growth.The hallway was modeled with the destruction in mind.Conveying a disturbing smile for Abigail Arnold was a fine line between being creepy or silly. We did a bunch of iterations to find the smile that worked the best, Millet remarks. We had some versions where it was definitely not creepy. It would make you laugh as soon as you see it. It was a combination of not just the mouth, but the look in the eyes and the way all of the little muscles in the face move. Everyone is an expert because we all look at faces every day, so its a much less forgiving thing to do than pretty much any other aspect of what we do in visual effects. Michael Chaves did concept art to illustrate what he wanted. That was incredibly helpful, because we had an exact target to match. The goal for us was to try to match his concept and give it life. The smile was exaggerated then rolled back. We did a bunch of iterations with a different range and smile, but all going much further than what we knew was needed. That helped us not to baby-step the process because the last thing you want is, Oh, a little bit more. And you spend weeks doing that. We went way out in terms of how wide that smile was and showed all of those versions. Once the director was happy with one of them, we actually selected a range to give us an idea of what to work within, and then we made that range as good as we could.[Director Michael Chaves concept art] was incredibly helpful, because we had an exact target to match. The goal for us was to try to match his concept and give it life.Alex Millet, Visual Effects Supervisor, Digital DomainA signature terrifying prop for the franchise is the Conjuring Mirror.A signature terrifying prop for the franchise is the Conjuring Mirror. The work for us was adding the crack in the mirror throughout a lot of different sequences in the movie, Millet explains. First, it was establishing the look of that crack and getting it to read the same across the various shots. The thing with the crack was that in some shots, its going to look awesome and perfect, but in a different lighting condition you dont get the same highlights and, incidentally, the shape feels different even though its the same. The sequence in the hallway was a whole different thing. We had to completely rebuild the mirror in CG so we could animate it. On set, they tried to avoid any reflection problems, but with a big mirror you cant avoid it. There were a bunch of shots where we had to get rid of reflections showing the part of the set that wasnt built or crew members or a giant camera rig. The work for us was to rebuild the entire hallway CG so we could take over any reflection and rebuild any reflection that we needed to do. The hallway gets destroyed. We built the entire hallway then animated the CG mirror. Something we didnt expect was the mirror on set was shorter than the actual mirror we needed to build, so getting the mirror to reach everywhere in the walls was a fun challenge for animation and effects. Once that was figured out, we added some extra geometry behind the walls and under the floor because when we destroy everything, we will see stuff there. Then we moved forward with our effects destruction, so there were different layers of drywall, studs, installation and smoke. That was cool.The factory had to be seen in every shot that takes place in the mill town.A LEGO approach was adopted when constructing the various houses that populate a neighborhood.Set dressing, like wet asphalt and lights in the distance, provided the desired scope and mood for the nighttime shots.Practical houses were constructed, which helped ground the digital extensions.The crack in the Conjuring Mirror had to appear as if there was no point of impact.The Conjuring franchise is based on the exploits of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren, portrayed by Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga.Construction of the small mill town was tackled as if it was a LEGO set. We wanted to build a house in such a way that floors, colors and roofs could be easily changed, Millet remarks. A lot of our houses were built in three layers: ground floor, first floor and roof. The houses were built in a modular way so we could quickly populate the street, create a layout, and show something that gives you a feel for the street versus iterating on different houses. Geography had to be kept in mind to avoid discontinuity. When the characters drive on the bridge we needed to make sure that it feels like theyre going in the right direction. We had to have the factory looming above the town at all times, so it had to be in such a place that we would always see it when were at street level and in those shots where we go up a little bit. The set dressing can be unlimited. We had birds, cars, every plant has wind in it, and digital people looking around. There are lot of things going on, and as soon as you have to do that, it immediately gets rid of any 2D or matte painting approach. You have to build and animate it. But we also didnt want to take away from the action in the plate. Millet concludes, Overall, this was a small project, but ambitious with the work that had to be done within the given timeline. It was a great project to work on, and the challenges were interesting.0 Comments ·0 Shares -

PART 2: UNION VFX CHANNELS CHAOS FOR 28 YEARS LATERvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of Union VFX and Sony/Columbia Pictures.Partners in crime for over 23 years, filmmaker Danny Boyle, cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle and Union VFX Co-Founder Adam Gascoyne have reunited for 28 Years Later, the third instalment of the zombie franchise established by Boyle and Alex Garland, which continues to explore the downward spiral of humanity as civilization gives way to primeval chaos. Danny and Anthony arent making traditional visual effects-driven films, notes Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor. Everything we do has to feel embedded in the photography, very much in the background. That means theres a huge amount of planning to give them the freedom to shoot organically and focus on performance, without visual effects interfering in that process.A significant landmark is the causeway that connects Holy Island to the mainland.The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope. Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But its what made the project so creatively satisfying.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorServing as points of reference were the first two films. We went back to 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later to study the aesthetic and mood, particularly how they handled realism and chaos, Gascoyne states. The first film especially had such a gritty, DIY sensibility that we wanted to retain, while expanding the scale. There were early conversations around continuity and where the story might go next, so we tried to lay groundwork visually without limiting future storytelling. Like the onscreen characters, Boyle is instinctual. Danny communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. Hes very instinctual and might not say, I want a 3D fluid simulation here. But hell say, This needs to feel like a rupture. Or, Like a moment of beautiful violence. Its up to us to interpret that visually, and thats what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world. Holy Island (Lindisfarne) is a tidal island in Northumberland, England where the protagonists reside.Union VFX constructed the full tidal causeway in CG, including FX-driven water, mist, seaweed and bioluminescent interactions when characters stepped in.Arrows were all digital, including impacts and blood.The Happy Eater and Causeway sequences were heavily planned in the advance. We used previs for layout, timings, and to coordinate the choreography with stunts and practical effects, Gascoyne remarks. For complex effects sequences, like the gas explosion and tidal interaction, postvis helped evolve the final shots while working in parallel with the edit. Visual research was conducted for a variety of things. We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeways night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos. The Causeway Chase was the most complex sequence to execute as it features 130 shots that are mostly fully CG.Complicating matters was the choice of camera. The iPhone shoot was one of the biggest technical curveballs, Gascoyne acknowledges. We had 20-camera and 10-camera iPhone rigs, some hand-held and some bar-mounted for bullet-time shots. Matching and syncing these in post meant solving issues around chroma subsampling, stabilisation artifacts, clipped highlights and unrecorded focus shifts. Creatively, we had to make a forgotten, devolved world believable. One where nature has reclaimed infrastructure and humanity has gone feral. But it still had to feel intimate and human. Streamlining the visual effects process was not having to divide the digital augmentation among multiple vendors. Union VFX, being sole vendor, helped maintain consistency and allowed us to work fluidly across teams in London and Montral. We built custom tools to handle iPhone media, matchmove multi-cam rigs, and simulate natural phenomena like water and gas. Our pipeline had to be nimble. We had over 950 shots across the film, many of them subtle, and some incredibly complex, Gascoyne says. Danny [Boyle, director] communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. Hes very instinctual and might not say, I want a 3D fluid simulation here. But hell say, This needs to feel like a rupture. Or, Like a moment of beautiful violence. Its up to us to interpret that visually, and thats what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorThe world had to feel like it had been abandoned for decades, so Union VFX used procedural vegetation and overgrowth simulations to help show how nature had reclaimed space.Different stages of Inflected are encountered throughout 28 Years Later. We worked closely with prosthetics to build a multi-stage progression system, from early infection to full degeneration, Gascoyne states. Our role was to augment with subtle eye shifts, facial damage or infection bloom. We kept everything grounded, our job was never to overwrite their excellent work, but to push it further when needed. Impacting the creation of digital doubles was the prevailing nudity. There was little to no wardrobe or props to hide behind, so digital doubles had to stand up to full scrutiny, Gascoyne states. We developed anatomical shaders with nuanced textures for scars, grime and infection markers that blended cleanly with prosthetics. For crowds, we varied limb damage and posture stages to give a sense of physical deterioration without relying on costume coverage. The skies had to be reimagined for a world that has been without light pollution for 28 years.An important aspect of the environmental work was the overgrown vegetation. The world had to feel like it had been abandoned for decades, so we used procedural vegetation and overgrowth simulations to help show how nature had reclaimed space, Gascoyne describes. Sky replacements were frequent and important, particularly in sequences like the Causeway, where the fully CG aurora sky helped give a sense of time passing and nature expanding. The wildlife was expanded upon. We used digital deer, rats and occasional digital horses where safety or logistics prevented practical shots. The CG animals were integrated to feel completely part of the world. Pivotal to the narrative is the isthmus and the tide going in and out. Only a short water section was available on set, about 100 meters, but the script demanded something that felt 1.5 miles long. We built out the full tidal causeway in CG, including effects-driven water, mist, seaweed and bioluminescent interactions when characters stepped in. The waterline was animated based on real tidal cycle data, and the sky was a full CG aurora nebula with flocks of 10,000 murmuration birds. Visual effects worked closely with prosthetics to build a multi-stage progression system, from early Infection to full degeneration.The limited dynamic range of the iPhone 15 Pro Max meant that Union VFX had to match clipped whites and edge roll-off in their CG, especially in effects like explosions.Visual effects collaborated closely with stunts and special effects. From early prep, we were embedded in conversations with the stunt and special effects teams, Gascoyne explains. Our digital enhancements were always designed around what was captured practically, like blood impacts or interaction with the gas cloud. The bullet-time iPhone rig, used for capturing gore in motion, was developed collaboratively with grips, camera and effects teams to preserve performance while enhancing it digitally. Most of the principal photography was captured on location. Greenscreen was used only where absolutely necessary, like safety work or high-risk interactions. For instance, in gas cloud scenes or crowd extensions, we often worked from roto and grayscreen due to the iPhones limitations with color keying. The blood and gore had to feel real, not exploitative. Danny wanted it to hit emotionally, not gratuitously. For example, the CG arrows and their impacts were grounded in realistic physics, but enhanced to show how brutal and sudden violence can feel in that world. Many impacts were practical, but we helped extend the gore in edit or amplify the timing digitally. Prosthetic arrows were digitally extended.We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeways night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorMixing formats from XL1s to GoPros is a trademark of Anthony Dod Mantle. With iPhones, stabilization artifacts were a concern, Gascoyne notes. We couldnt rely on built-in smoothing, so we disabled it and corrected it manually. The limited dynamic range meant that we had to match clipped whites and edge roll-off in our CG, especially in effects like explosions. Chroma subsampling [4:2:2] meant greenscreen was unreliable, so for larger studio setups we used grayscreen and leaned heavily on roto. Matchmove was complicated by the unrecorded zoom/focus data, but overall, the iPhone footage brought a raw immediacy that worked beautifully with the story.As the sole visual effects vendor, Union VFX was responsible for 950 shots, many of which were subtle and some incredibly complex.The Causeway Chase was the most complex sequence to execute. Its 130 shots long, most of which are fully CG. We had to build the entire environment, tidal water, bioluminescence, a vast CG sky and animate 10,000 birds. Everything had to interact rain, feet in water, light bouncing off surfaces. Its ambitious, but were incredibly proud of how it turned out. Maintaining realism while embracing scale was the biggest challenge. The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope, Gascoyne remarks. Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But its what made the project so creatively satisfying. Gascoyne is looking forward to audience reaction to certain scenes. The Happy Eater sequence is a favorite. Its eerie, visually rich and emotionally intense. The CG gas and explosion were tricky, but they pay off. The Causeway Chase, too. Between the sky, the tide and the birds, its epic but grounded in emotion. The production was a unique experience for Gascoyne. Working on something that felt like both a return and a reinvention was incredibly rewarding. We hope the audience feels the grit and scale of this world and never notices most of what we did. Matching and syncing all the iPhones in post meant solving issues around chroma subsampling, stabilisation artifacts, clipped highlights and unrecorded focus shifts.Watch a dramatic VFX breakdown video from Union VFX that showcases the creative design work and depth of detail and that bring out all the horror in 28 Years Later.Click here: https://vimeo.com/1094786468?fl=pl&fe=vl0 Comments ·0 Shares

PART 2: UNION VFX CHANNELS CHAOS FOR 28 YEARS LATERvfxvoice.comBy TREVOR HOGGImages courtesy of Union VFX and Sony/Columbia Pictures.Partners in crime for over 23 years, filmmaker Danny Boyle, cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle and Union VFX Co-Founder Adam Gascoyne have reunited for 28 Years Later, the third instalment of the zombie franchise established by Boyle and Alex Garland, which continues to explore the downward spiral of humanity as civilization gives way to primeval chaos. Danny and Anthony arent making traditional visual effects-driven films, notes Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor. Everything we do has to feel embedded in the photography, very much in the background. That means theres a huge amount of planning to give them the freedom to shoot organically and focus on performance, without visual effects interfering in that process.A significant landmark is the causeway that connects Holy Island to the mainland.The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope. Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But its what made the project so creatively satisfying.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorServing as points of reference were the first two films. We went back to 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later to study the aesthetic and mood, particularly how they handled realism and chaos, Gascoyne states. The first film especially had such a gritty, DIY sensibility that we wanted to retain, while expanding the scale. There were early conversations around continuity and where the story might go next, so we tried to lay groundwork visually without limiting future storytelling. Like the onscreen characters, Boyle is instinctual. Danny communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. Hes very instinctual and might not say, I want a 3D fluid simulation here. But hell say, This needs to feel like a rupture. Or, Like a moment of beautiful violence. Its up to us to interpret that visually, and thats what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world. Holy Island (Lindisfarne) is a tidal island in Northumberland, England where the protagonists reside.Union VFX constructed the full tidal causeway in CG, including FX-driven water, mist, seaweed and bioluminescent interactions when characters stepped in.Arrows were all digital, including impacts and blood.The Happy Eater and Causeway sequences were heavily planned in the advance. We used previs for layout, timings, and to coordinate the choreography with stunts and practical effects, Gascoyne remarks. For complex effects sequences, like the gas explosion and tidal interaction, postvis helped evolve the final shots while working in parallel with the edit. Visual research was conducted for a variety of things. We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeways night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos. The Causeway Chase was the most complex sequence to execute as it features 130 shots that are mostly fully CG.Complicating matters was the choice of camera. The iPhone shoot was one of the biggest technical curveballs, Gascoyne acknowledges. We had 20-camera and 10-camera iPhone rigs, some hand-held and some bar-mounted for bullet-time shots. Matching and syncing these in post meant solving issues around chroma subsampling, stabilisation artifacts, clipped highlights and unrecorded focus shifts. Creatively, we had to make a forgotten, devolved world believable. One where nature has reclaimed infrastructure and humanity has gone feral. But it still had to feel intimate and human. Streamlining the visual effects process was not having to divide the digital augmentation among multiple vendors. Union VFX, being sole vendor, helped maintain consistency and allowed us to work fluidly across teams in London and Montral. We built custom tools to handle iPhone media, matchmove multi-cam rigs, and simulate natural phenomena like water and gas. Our pipeline had to be nimble. We had over 950 shots across the film, many of them subtle, and some incredibly complex, Gascoyne says. Danny [Boyle, director] communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. Hes very instinctual and might not say, I want a 3D fluid simulation here. But hell say, This needs to feel like a rupture. Or, Like a moment of beautiful violence. Its up to us to interpret that visually, and thats what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorThe world had to feel like it had been abandoned for decades, so Union VFX used procedural vegetation and overgrowth simulations to help show how nature had reclaimed space.Different stages of Inflected are encountered throughout 28 Years Later. We worked closely with prosthetics to build a multi-stage progression system, from early infection to full degeneration, Gascoyne states. Our role was to augment with subtle eye shifts, facial damage or infection bloom. We kept everything grounded, our job was never to overwrite their excellent work, but to push it further when needed. Impacting the creation of digital doubles was the prevailing nudity. There was little to no wardrobe or props to hide behind, so digital doubles had to stand up to full scrutiny, Gascoyne states. We developed anatomical shaders with nuanced textures for scars, grime and infection markers that blended cleanly with prosthetics. For crowds, we varied limb damage and posture stages to give a sense of physical deterioration without relying on costume coverage. The skies had to be reimagined for a world that has been without light pollution for 28 years.An important aspect of the environmental work was the overgrown vegetation. The world had to feel like it had been abandoned for decades, so we used procedural vegetation and overgrowth simulations to help show how nature had reclaimed space, Gascoyne describes. Sky replacements were frequent and important, particularly in sequences like the Causeway, where the fully CG aurora sky helped give a sense of time passing and nature expanding. The wildlife was expanded upon. We used digital deer, rats and occasional digital horses where safety or logistics prevented practical shots. The CG animals were integrated to feel completely part of the world. Pivotal to the narrative is the isthmus and the tide going in and out. Only a short water section was available on set, about 100 meters, but the script demanded something that felt 1.5 miles long. We built out the full tidal causeway in CG, including effects-driven water, mist, seaweed and bioluminescent interactions when characters stepped in. The waterline was animated based on real tidal cycle data, and the sky was a full CG aurora nebula with flocks of 10,000 murmuration birds. Visual effects worked closely with prosthetics to build a multi-stage progression system, from early Infection to full degeneration.The limited dynamic range of the iPhone 15 Pro Max meant that Union VFX had to match clipped whites and edge roll-off in their CG, especially in effects like explosions.Visual effects collaborated closely with stunts and special effects. From early prep, we were embedded in conversations with the stunt and special effects teams, Gascoyne explains. Our digital enhancements were always designed around what was captured practically, like blood impacts or interaction with the gas cloud. The bullet-time iPhone rig, used for capturing gore in motion, was developed collaboratively with grips, camera and effects teams to preserve performance while enhancing it digitally. Most of the principal photography was captured on location. Greenscreen was used only where absolutely necessary, like safety work or high-risk interactions. For instance, in gas cloud scenes or crowd extensions, we often worked from roto and grayscreen due to the iPhones limitations with color keying. The blood and gore had to feel real, not exploitative. Danny wanted it to hit emotionally, not gratuitously. For example, the CG arrows and their impacts were grounded in realistic physics, but enhanced to show how brutal and sudden violence can feel in that world. Many impacts were practical, but we helped extend the gore in edit or amplify the timing digitally. Prosthetic arrows were digitally extended.We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeways night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos.Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects SupervisorMixing formats from XL1s to GoPros is a trademark of Anthony Dod Mantle. With iPhones, stabilization artifacts were a concern, Gascoyne notes. We couldnt rely on built-in smoothing, so we disabled it and corrected it manually. The limited dynamic range meant that we had to match clipped whites and edge roll-off in our CG, especially in effects like explosions. Chroma subsampling [4:2:2] meant greenscreen was unreliable, so for larger studio setups we used grayscreen and leaned heavily on roto. Matchmove was complicated by the unrecorded zoom/focus data, but overall, the iPhone footage brought a raw immediacy that worked beautifully with the story.As the sole visual effects vendor, Union VFX was responsible for 950 shots, many of which were subtle and some incredibly complex.The Causeway Chase was the most complex sequence to execute. Its 130 shots long, most of which are fully CG. We had to build the entire environment, tidal water, bioluminescence, a vast CG sky and animate 10,000 birds. Everything had to interact rain, feet in water, light bouncing off surfaces. Its ambitious, but were incredibly proud of how it turned out. Maintaining realism while embracing scale was the biggest challenge. The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope, Gascoyne remarks. Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But its what made the project so creatively satisfying. Gascoyne is looking forward to audience reaction to certain scenes. The Happy Eater sequence is a favorite. Its eerie, visually rich and emotionally intense. The CG gas and explosion were tricky, but they pay off. The Causeway Chase, too. Between the sky, the tide and the birds, its epic but grounded in emotion. The production was a unique experience for Gascoyne. Working on something that felt like both a return and a reinvention was incredibly rewarding. We hope the audience feels the grit and scale of this world and never notices most of what we did. Matching and syncing all the iPhones in post meant solving issues around chroma subsampling, stabilisation artifacts, clipped highlights and unrecorded focus shifts.Watch a dramatic VFX breakdown video from Union VFX that showcases the creative design work and depth of detail and that bring out all the horror in 28 Years Later.Click here: https://vimeo.com/1094786468?fl=pl&fe=vl0 Comments ·0 Shares -