The surprising origins and alien inspirations of Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity

www.gamedeveloper.com

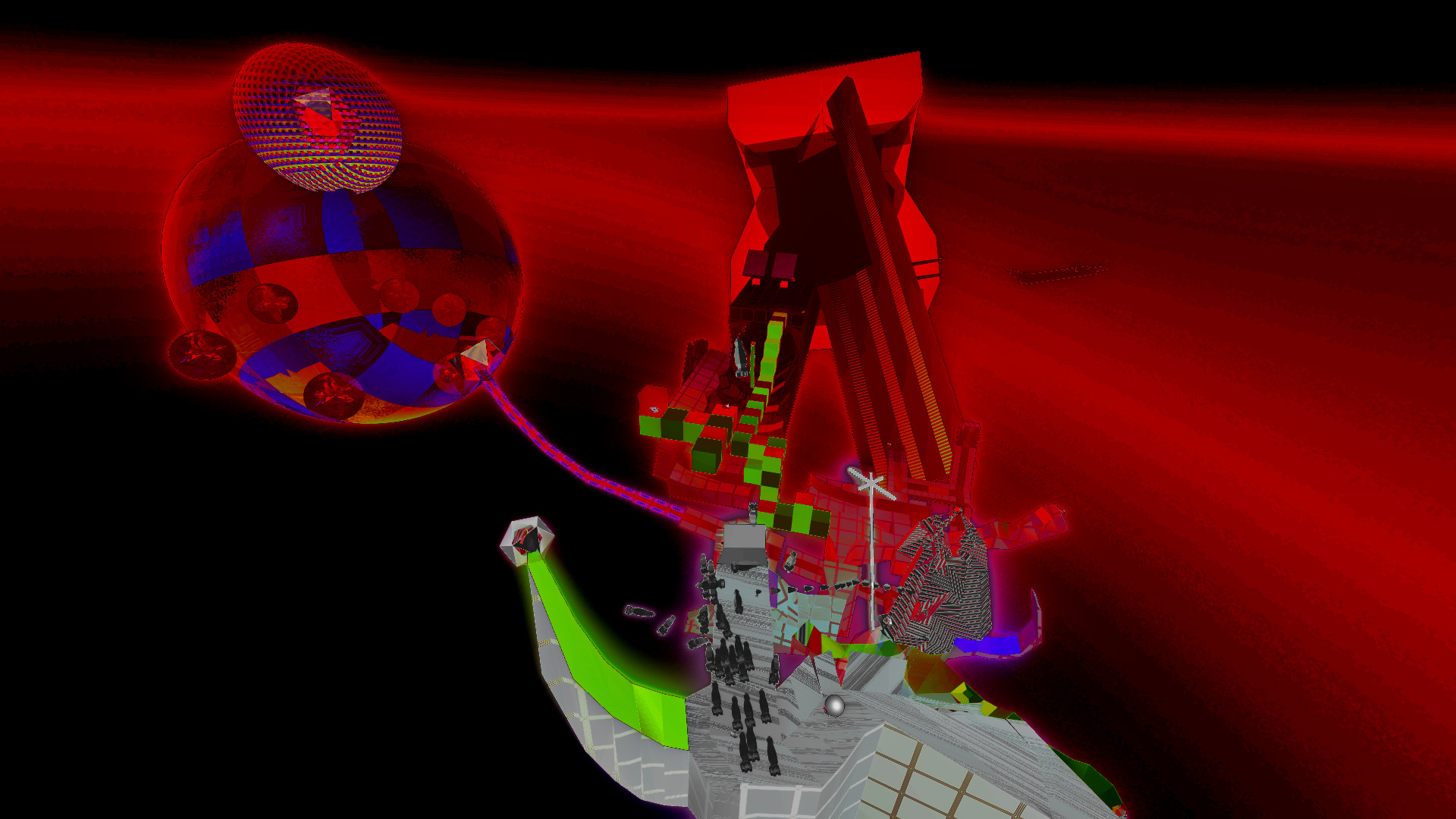

TheIGF(Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium.This year, Game Developer sat down with the finalists for the IGF's Nuovo Award and the Seamas McNally Grand Prizeahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa.Nuovo Award nominee Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity is an experience in movement and transformation across stunning,alien worlds that you're tasked with bouncing, flinging, and leaping through.Game Developer caught up with Sam Atlas, the Nuovo Award-nominated game's creator, to talk about its surprising origins in body horror, the thought and design processes that go into shaping the game's colorful landscapes, and the challenges that come from creating visual accessibility features in a game that can sometimes border on visually-overwhelming with its shifting cosmos.Who are you, and what was your role in developing Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity?I'm Sam Atlas! I did everything except the music and some other sound effects for Extreme Evolution, which were composed and recorded by DL Salo.What's your background in making games?This is my 4th standalone game and the follow-up to the Space Hole trilogy. Before my own games, I made mods especially on the Source (Half Life 2) engine (I generally made level pack style single-player mods).I've got a background in general software, so I approach game development from a holistic/ synergistic approach (i.e. mix tech and design).How did you come up with the concept for Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity?It started as a vague project called Flesh, which was going to be more of a horror game about an organism seeking humanity through the mechanical accumulation of human parts.It was a brain in a void, and the game would have been in first person, with real-life footage of hands/organs as the tools you use. These tools would be used to, for example, paddle your hand to swim the psychic-brain around.Accumulation and the imitation of humanity were themes; but it was more body horror.What development tools were used to build your game?Unity, chatGPT, VSCode, Blender (lightly for certain 3d), Unity ProBuilder (the majority of custom 3d meshes), Paint.NET, Davinci Resolve, Audacity, and my camera phone! I take videos/photos of natural patterns, such as waves or light reflecting on water, or fire, and loop those in the video editor (by flipping and tessellating the videos).Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity explores many different forms of movement as you explore its dizzying visual landscapes. What thoughts went into creating the various ways players could evolve to move around? What made a form of movement feel interesting to you to include in the game?One core design idea for the game was "a platformer where every pickup extends your range." The main design idea here was to begin stumblinga speck of dust or a pebble rolling/shamblingand by the end to be a maximally-empowered platformer (i.e., fling yourself, drive up walls, hang in the air indefinitely etc). So, a lot of the form design derived from trying to find a middle ground between "can go anywhere" and "can only tumble along the ground." The name "Extreme Evolution" alludes to this: starting at the most basic (a clunky, oblong egg) and eventually the most obscene (Deity, a hovering orb that spits out projectiles that seek pickups and count as part of your body). "Drive to Divinity" is also a reference to this, and another literal description of the game.Movement often comes with unique shapes that feel alien, but also convey some of their capabilities to the player through shape and form. What thoughts went into making movement feel somewhat clear while also keeping things mysterious?For this, I think the key is to make the rules of the world consistent and to use visual cues to explain how objects interact. Furthermore, I have a short flavor text for each form, which, when combined with its name, was intended to convey some efficient expectation to the player. For example, "Cor" is "the oblong car," and it is both a corrupted motorcycle and a corruption of the word "Car." But as is the case in nature, the "Car" remains around in the world as well. I wanted the world to have a sense of logic and consistency to it, as well as a mix of earth-references and references that seem alien.You put a great deal of thought and work into the visuals of your games, crafting this sense of moving through higher realities of color and shape. What feelings were you looking to evoke in the player with the cosmic visual work in this game?My goal is to create an environment that you haven't seen before. I think the fun of the game is a repeating cycle of "what's over there?" and following intuition. I want to encourage the player to feel in control of their experience. I make games essentially by playing through them extremely slowly, making the levels in front of me as I go. So, whichever game I make tends to represent my feelings during development, or the feeling that I wanted.What thoughts went into birthing this whole new visual cosmic universe? How do you craft whole worlds to platform in that capture this sense of being otherworldly and alien through your use of color and shape?Iteration, willingness to cut ideas/areas, and gradually narrowing the focus of my work as a level progresses. It takes many, many coats of paint (and sometimes major cuts) to make sure each zone has a good feeling. For this game, the whole overall thing was "playable" a year before release in an alpha form, but everything went through major revisions following that.Basically, I become more focused/editorial as I get deeper into development, but every level starts with some kind of simple idea (for example, "Thyroid" was conceived as "Jump," a delta where you are given many exits to choose between; the name "Thyroid" was chosen due to the geographical notion of the thyroid as a gateway to the body from the head). Sometimes, the name of the level is a remnant of that original idea and separate from the actual level (which sometimes is funny, so I leave it in). Often, levels become most extreme at some middle point in developmentthe most visual elements, the most pickups, etc. Then, over time, like a sine wave, I cut/uncut stuff until it feels right.What challenges do you face in creating visuals that can be so powerful they border on overwhelming? What is it like to pore over these visions as you weave them together while developing the game?I like to develop the game intuitively, so the border between "too much" and the right amount is always revealed only by the end of the project (but really, many years after).I also will sometimes revert to an earlier version but keep a single element from the newer (cut) revision, resulting in a hybrid that is mostly the old but with some specific improvement. I also have learnt to be sensitive (and un-offended) to the way people respond to visuals; people respond in a very specific way (they avoid playing) if it's making them nauseous, so I do mix my own feelings with the (sometimes visceral) player reactions. If you go too far everywhere, it also reduces the sense of change when entering spaces that are more or less intense.You have put in some systems to help players who may have difficulties or health issues that are affected by the game's visuals, but they cannot be turned all the way off. What ideas go into balancing the need to protect the player with preserving the vital visual style of Extreme Evolution: Drive to Divinity?I think of accessibility as a natural tool to make games better. I think it's absolutely a balance; another element of this issue (ensuring people don't have a physically painful experience playing the game) is to represent the game as accurately as possible in marketing materials. And, while you can turn lots of the effects off, there is a limit because I wanted to make sure every version of the game at least emphasized the separation of foreground and background.Using the Mod menu (unlocked about an hour into the game) you can go further into untested effects. However, because of the large amount of complex color correction, there are cases where turning an effect off might result in the ground and sky being too close in color. The major effect which produces nauseous feelings in my game is using uncleared buffers; this results in pixels which can change each frame as their behavior becomes so unpredictable. To balance this, I've tried blurring in the past, but now I use blur (and motion blur) as sparingly as possible because I find it tends not to be worth its nauseousness-to-budget, so to speak.The representation of nothingness as infinitely-complex static feels too perfect and fitting for the game and the game's themes (nothingness/everythingness) to not be on by default in my mind, but I also have no qualms about the idea that some future playerbase might prefer it off. Ownership and setting your own goals is an intention of the game. I mostly focus on making sure the geometry of the level still reads and making sure the default modes reflect what I personally prefer when enabling accessible graphics options. I'm happier with how I've managed the accessibility features in Extreme Evolution over Space Hole 2020, but it's something I spend a lot of time thinking about for future projects.

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·37 Views