See the 'Fantastical Beasts and Foliage' Featured in These Rare, Newly Discovered Tudor Wall Paintings

Cool Finds

See the ‘Fantastical Beasts and Foliage’ Featured in These Rare, Newly Discovered Tudor Wall Paintings

Created in the Grotesque style, the 16th-century images—revealed by renovations at a lodge in England—mimic historic textile designs

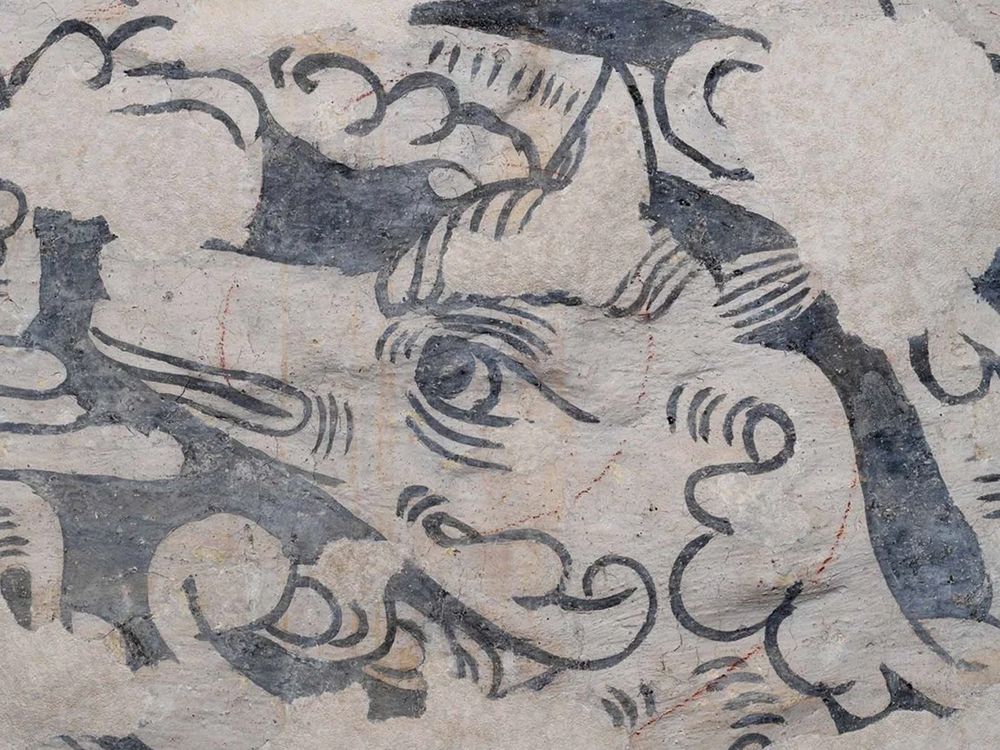

One of the wall paintings discovered at the Ashes, a Tudor-era guest house in northeastern England, depicts a dog's head.

Historic England Archive

For over two decades, Jen and Richard Arkell have owned and operated the Ashes, a quaint guest house nestled along the wooded banks of the River Tees in northeastern England.

But the building’s history stretches back much further than the past 20 years. When the Arkells began renovations on one of the upstairs bedrooms recently, they found vivid new evidence of the Ashes’ former life as a Tudor-era hunting lodge.

Scraping back layers of plaster, the pair discovered wall paintings of “fantastical beasts and foliage” dating back to the 16th century, according to a statement from Historic England, a public organization that preserves the country’s historic sites.The Arkells were astonished to see the Grotesque-style decorations, which feature animal heads swirling into clouds, hares trotting and sneering human profiles. “Removing old failing plaster to find these remarkable motifs and faces looking back at us is a moment we will never forget,” they say in the statement.

Although small sections of wall art were found at the lodge in the 1970s and again in more recent decades, this latest discovery suggests that the designs covered a much greater area in the lodge than previously known. They also feature a “combination of motifs [that] is unusual even by national standards,” says Myra Tolan-Smith, a listing advisor at Historic England, in the statement.

Tudor-era artists created the wall paintings with a fresco secco technique. Whereas typical frescoes are painted onto wet plaster, allowing colorful pigments to soak into the surface, fresco secco uses a dry plaster. As a result, the colors are more muted, but the designs retain a folksy authenticity that is thought to replicate textile designs of the time, according to Historic England.

An abstract, "fantastical" section of the wall painting

Historic England Archive

“They’re not symmetrical, and it’s all very freehand. It’s lovely,” Andrea Kirkham, a wall painting conservation expert brought in by the Arkells, tells the Guardian’s Mark Brown.

While the painting’s subjects are typically associated with hunting, their strange arrangements and Grotesque ornamentation suggest they were intended for the amusement and entertainment of the lodge’s guests.

As Henry Peacham, a writer at the time, put it, these kinds of “unnatural or unorderly” designs existed “for delight’s sake, of men, beasts, birds, fishes, flowers … without (as we say) rhyme or reason.”

Last year, researchers with Historic England used dendrochronology—a method of measuring tree growth rings—to date the Ashes. Their research concluded that the timbers used to build the lodge were felled in the winter of 1561-1562, placing its construction during the earlier years of the reign of Elizabeth I, who ruled England between 1558 and 1603.

That gives historians some idea of when the wall paintings may have been completed, offering insight into the artistic sensibilities of those who could afford to own lodges and commission art during the mid-16th century.

A section of the wall art depicting a hare

Historic England Archive

The lodge first appears in the historical record as part of the 1592 will and inventory of William Simpson, the bailiff of nearby Castle Sowerby, an ancient parish in Cumbria, per Historic England. Listed alongside other assets like furniture and farm animals, the house may well have counted Simpson and his family as its first residents. It was likely the Simpsons who commissioned the paintings to cover the house’s walls.

As British heritage minister Baroness Twycross tells Cumbria Crack, the paintings offer another “glimpse into our Tudor past,” more vivid and more mysterious than any inventory list.

Along with the main lodge building and adjacent agricultural sites, the paintings now fall under Historic England’s Grade II* protection status, ensuring their preservation for years to come.

“They are social history,” Kirkham tells the Guardian. “They tell us an awful lot about people’s tastes, attitudes, their ideologies, the way they use color or the way they use materials, the designs they choose. They tell us about their interests and how they wish to be seen by others.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.