ARSTECHNICA.COM

Rover finds hints of an ancient Martian carbon cycle

Carbon sequestration

Rover finds hints of an ancient Martian carbon cycle

Rather than cycling, some of Mars' carbon took a one-way trip into rocks.

Jacek Krywko

–

Apr 18, 2025 1:22 pm

|

8

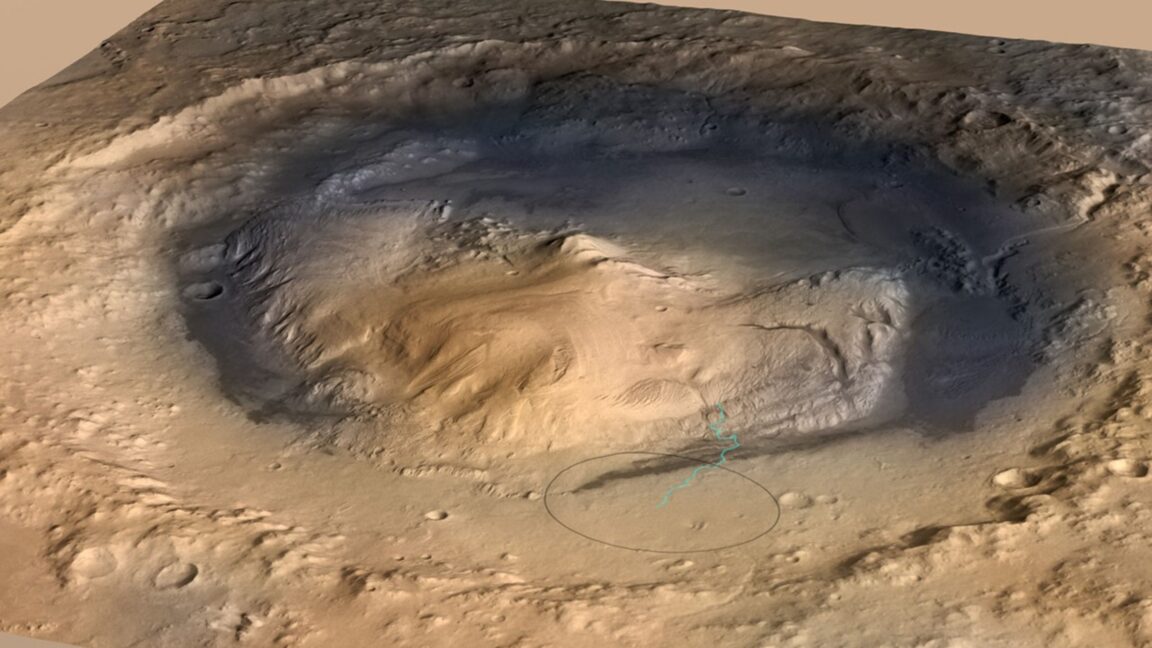

A view of Gale Crater showing the rover's path up Mount Sharp.

Credit:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS

A view of Gale Crater showing the rover's path up Mount Sharp.

Credit:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Learn more

Mars has not always been a seemingly lifeless red desert. We have evidence that billions of years ago it had a warm, habitable climate with liquid water in lakes and flowing rivers, which is somewhat confusing, given that Mars is much farther from the Sun than the Earth and that the Sun was much less bright back then. “In order for Mars to be warm enough to host liquid water, there must have been a lot of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” says Benjamin Tutolo, a researcher at the University of Calgary. “The question we’ve been asking for at least 30 years was where the record of all this carbon is.”

Tutolo led a new study of rock samples collected by the Curiosity rover that might have answered this question.

The tallest sediment stack

The mystery of Mars’ missing carbon stems from two seemingly conflicting results. On the one hand, we have already found dried riverbeds and lakes on the surface of Mars, so we know there must have been liquid water on its surface at some point. To account for the presence of this water, every Martian climate model we have run indicates that huge amounts of atmospheric carbon were needed to provide a sufficient greenhouse effect to keep the surface temperature above freezing. But the data we were getting from satellite observations of Mars found much less carbon in the Martian soil than those climate models would suggest. “So, either the models were incorrect—and there’s no good reason to believe that—or there really was lots of carbon in the Martian atmosphere,” Tutolo says.

The only way to resolve that mystery was to put boots on the ground and look for that carbon. Or wheels.

Curiosity rover was called Mars Science Laboratory for a reason. It went to the red planet fitted with a suite of instruments, some of which even the newer Perseverance was lacking. These enabled it to analyze the collected Martian rocks on the spot and beam the results back to Earth. “To get the most bang for the buck, NASA decided to send it to the place on Mars called the Gale Crater, because it was the tallest stack of sediments on the planet,” Tutolo says. The central peak of Gale Crater was about 5 kilometers tall, created by the ancient meteorite impact.

The Curiosity mission started near the bottom of the crater, at the base of a formation called Aeolis Mons, or Mount Sharp, where NASA expected to find the earliest geological samples. The idea then was to climb up Mount Sharp and collect samples from later and later geological periods at increasing elevations, tracing the history of habitability and the great drying up of Mars. On the way, the carbon missed by the satellites was finally found.

An imperfect cycle

Tutolo’s team focused their attention on four sediment samples Curiosity drilled after climbing over a kilometer up Mount Sharp. The samples were examined with the rover’s Chemistry and Mineralogy instrument, which uses X-ray diffraction to determine their composition. It turned out the samples contained roughly between 5 and 10 percent of siderite. “It was an iron carbonate, directly analogous to a mineral called calcite found in sedimentary rocks like limestone. The difference is it has iron in its cation site rather than calcium,” Tutolo explained. “We expected that because Mars is much richer in iron—that’s why it is the red planet.”

The siderite found in the samples was also pure, which Tutolo thinks indicates it has formed through an evaporation process akin to what we see in evaporated lakes on Earth. This, in turn, was the first evidence we’ve found of the ancient Martian carbon cycle. “Now we have evidence that confirms the models,” Tutolo claims. The carbon from the atmosphere was being sequestered in the rocks on Mars just as it is on Earth. The problem was, unlike on Earth, it couldn’t get out of these rocks.

“On Earth, whenever oceanic plates get subducted into the mantle, all of the limestone that was formed before gets cooked off, and the carbon dioxide gets back to the atmosphere through volcanoes,” Tutolo explains. Mars, on the other hand, has never had efficient plate tectonics. A large portion of carbon that got trapped in Martian rocks stayed in those rocks forever, thinning out the atmosphere. While it’s likely the red planet had its own carbon cycle, it was an imperfect one that eventually turned it into the lifeless desert it is today.

But Tutolo’s work didn’t provide all the answers.

Persisting mysteries

The problem is, the missing Martian carbon found by Tutolo’s team doesn’t explain everything about its past climate. Even with huge amounts of carbon dioxide (enough to give Mars one Earth atmosphere’s worth of pressure), Tutolo thinks it would still be quite challenging to warm the planet.

Another mystery that remains is that Martian habitability was seemingly intermittent and fluctuating. “It doesn’t seem like the full first billion years were warm and wet on Mars, so how do we place constraints on the habitable conditions on Mars?” Tutolo wonders.

But before tackling more far-reaching questions, his team wants to work on new Mars climate models that will reflect these new findings. Tutolo suspects some of the siderite was redissolved and returned some of its carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. The new models he wants to set up will attempt to pinpoint the timing of this process—how long the carbon stayed trapped in the siderite and how much of it was potentially cycled back. “That would enable habitability for longer than if it was just permanently sequestered,” Tutolo says. “That’s the big thing I’m going to work on but have been too busy to get to.”

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.ado9966

Jacek Krywko

Associate Writer

Jacek Krywko

Associate Writer

Jacek Krywko is a freelance science and technology writer who covers space exploration, artificial intelligence research, computer science, and all sorts of engineering wizardry.

8 Comments

0 Комментарии

0 Поделились

48 Просмотры