Artificial 'Brain' Aims to Allow Composer to Keep Making Music Three Years After His Death

Art Meets Science

Artificial ‘Brain’ Aims to Allow Composer to Keep Making Music Three Years After His Death

Before dying in 2021, Alvin Lucier donated blood for “Revivification,” an installation that generates sound in response to neural signals

Lillian Ali

- Staff Contributor

April 2025

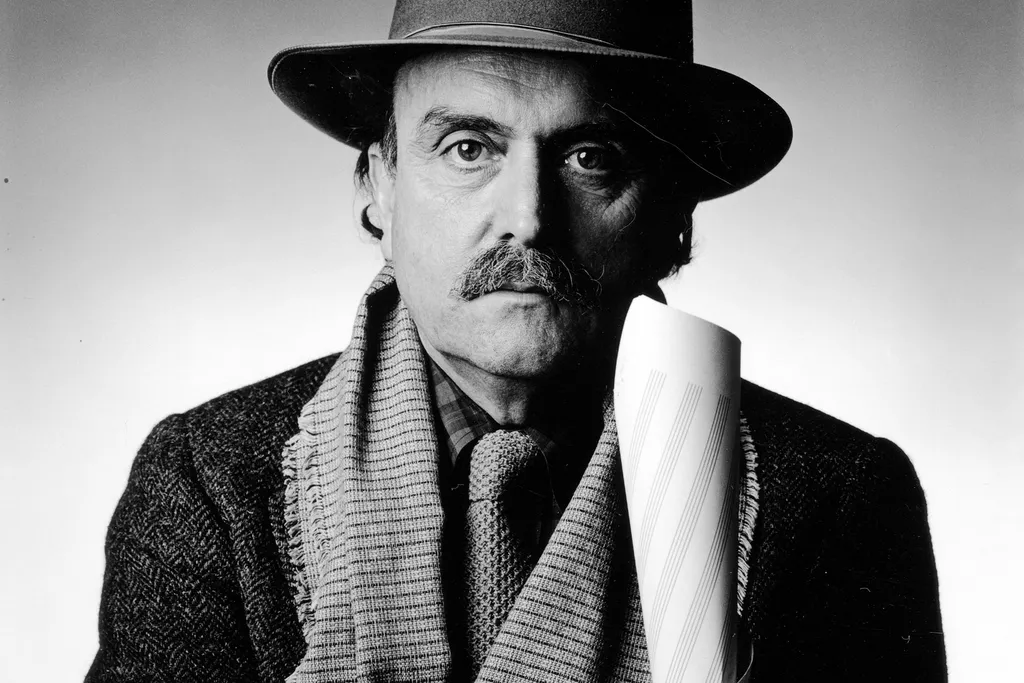

Composer Alvin Lucier in 1986

Jack Mitchell / Getty Images

At the Art Gallery of Western Australia, mallets periodically strike 20 wall-mounted brass plates, sending sound ringing through the room. They are controlled by a combination of man and machine: On a pedestal in the center of the gallery, two small, white blobs send electrical signals to the mallets, prompting them to strike.

The blobs are cerebral organoids, artificial structures that mimic parts of a human brain. They’re made from the cells of Alvin Lucier, an American composer who died in 2021.

In 2018, Lucier began working with a group of artists and scientists on a project called “Revivification,” which would continue generating art after the composer’s death.

Cerebral organoids on a mesh of electrodes

Art Gallery of Western Australia

“We have developed a brain on a dish, more or less, that has the ability to take action in the real world,” Nathan Thompson, one of the artists behind the installation, tells NPR’s Chloe Veltman.

Thompson created the installation along with artists Guy Ben-Ary and Matt Gingold, as well as University of Western Australia neuroscientist Stuart Hodgetts. A year before he died, Lucier donated blood for the project. The team then reprogrammed his blood cells into stem cells, which were used to make the “brain on a dish.” The neuronal structures sit on a mesh of electrodes, which capture neural signals to send to the mallets. The mallets generate “complex, sustained resonances that fill the space with sound,” per a statement from the gallery.

During his lifetime, Lucier’s work had always been experimental, and his music frequently drew from the physics of sound. The composer “began many of his projects by wondering what kinds of sounds would emerge from a specific process, like tapping a pair of pencils or detecting brain waves,” as the New York Times’ Allan Kozinn wrote in his 2021 obituary. In one of Lucier’s most famous pieces, “I Am Sitting in a Room” (1969), he recorded himself reading a passage, then played the tape and re-recorded it, repeating this process until the words became unintelligible.

Alvin Lucier on "I am sitting in a room"

Watch on

Rather than “simply preserving Alvin Lucier’s music or creating a tribute to his work,” “Revivification” aims to “fundamentally reimagine artistic immortality by creating a living extension of Lucier’s creative essence,” Ben-Ary, Thompson and Gingold tell Forbes’ Leslie Katz.

This “fundamental reimagining” prompts questions about the nature of art and consciousness—and whether consciousness is required to produce art. “Creativity really has to have a conscious element to it,” Indre Viskontas, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of San Francisco, explains to NPR. “I don’t think this particular piece of art is conscious. Those cells have no intention.”

The artists encourage this debate. Speaking with the Guardian’sThe team hopes to learn whether the cells are capable of changing in response to their surroundings. Noise from the gallery, such as guests speaking, is converted into electrical signals that are fed back into the blobs. “We’re very interested to know whether the organoid is going to change or learn over time,” Ben-Ary tells the Guardian.

“We are really interested in these big questions,” Thompson explains to the publication. “But this work is not giving the answers. Instead, we want to invite conversations. … Can creativity exist outside the human body? And is it even ethical to do so?”

“Revivification” is on view at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth through August 3, 2025.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.