WWW.SCIENTIFICAMERICAN.COM

CO₂ Surged Last Year, but the Trump Administration Has Downplayed the Alarming Data

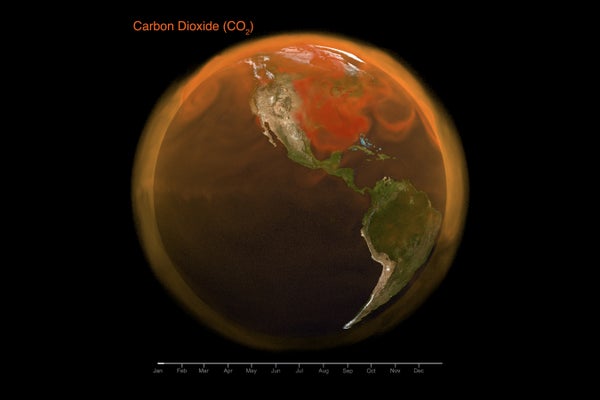

April 25, 20254 min readTrump’s NOAA Has Downplayed an Alarming Finding: CO₂ Surged Last YearUnder the Trump administration, NOAA has minimized an announcement that climate-warming carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere grew at a record-breaking speed in 2024By Chelsea Harvey & E&E News Volumetric visualization of the total carbon dioxide (CO₂) on a global scale added on Earth's atmosphere over the course of the year 2021. NASA's Scientific Visualization StudioCLIMATEWIRE | Climate-warming carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere grew at a record-breaking speed in 2024, surging by 3.7 parts per million, a recent NOAA data analysis has found.It’s one of the agency’s biggest scientific findings of the year — yet the research largely has flown under the radar after NOAA officials took steps to minimize the announcement.Instead of publishing a press release or a featured article online, the agency described the findings only in social media posts on Facebook and on X. And the posts failed to highlight the dataset’s most important finding: that last year’s CO₂ concentrations jumped by an unprecedented amount.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.That’s a departure from the agency’s historical approach to public communication. NOAA typically releases a public report each spring, prominently featured on its website, describing the previous year’s greenhouse gas concentrations. It also usually sends a press release to members of the media.Last year’s report, for instance, noted that carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide concentrations all continued to climb in the atmosphere in 2023.According to a source with knowledge of the 2024 analysis, NOAA staff prepared a public web story this year as usual. But officials nixed the report at the last minute, instead releasing the findings only on social media. The source was granted anonymity because they feared reprisal from the Trump administration.A NOAA communications officer did not respond to a request for comment.The move is part of a broader assault on NOAA science and public communications by the new administration.Last month, the agency confirmed it was ending its regular monthly climate briefings, in which NOAA scientists presented climate and weather data to the media. That's on top of widespread layoffs this year at the agency. And a recent proposal from the White House Office of Management and Budget would dramatically reorganize the agency and terminate much of its climate work — eliminating its entire Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research.A NOAA official suggested that downplaying the new CO₂ data has dampened media attention on what otherwise would have been a major climate headline. The scientific findings were reported earlier this month by The Washington Post, and the suppressed web story was reported by CNN earlier this week. There’s otherwise been little news reported on the subject.But scientists say it’s a finding that’s worth more attention — and more worry. Some researchers believe last year’s CO₂ spike is evidence that the Earth system itself is becoming more vulnerable to the impacts of rising temperatures.Natural landscapes, such as forests and wetlands, historically have acted as a carbon sink — soaking up excess CO₂ emissions and helping to offset some of the impacts of climate change. But some of these ecosystems may be breaking down under the stress of continued warming, with the added side effects of droughts and wildfires. And they’re storing less carbon in the process.“In my opinion, there is no reason to believe that this will not continue with further dry years in the future,” said Philippe Ciais, a climate scientist at the Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace in France.Ciais was not involved with the NOAA analysis, but he co-authored a recent preliminary study — not yet peer-reviewed — investigating the reasons for high CO₂ growth in 2023 and the first half of 2024. The study included a variety of real-life data sources, including satellite measurements, as well as complex Earth system models. And it found that some of the Earth’s natural carbon sinks are declining.The tropics, in particular, began to lose an unusually high amount of carbon beginning in the middle of 2023, Ciais said. That’s due in part to an increase in drought and wildfires in places such as the Amazon. Those losses continued into 2024 — and while the study’s timeline ends at the beginning of last July, Ciais suspects they’ve probably continued into 2025 as well.The effects are partly due to the influence of El Niño, a natural climate cycle that causes periodic drying in the tropics. But that can’t explain everything. For one thing, the recent El Niño was not particularly strong compared with some other recent events. And it also ended in the first half of 2024, while dry conditions persisted in the tropics for the rest of the year.More studies are needed to fully understand what happened in 2024. But Ciais and other scientists are worried last year’s events could point to a kind of climate feedback loop in which rising temperatures cause natural ecosystems to deteriorate, releasing more carbon into the atmosphere and causing the planet to warm even faster.“With one year you cannot say that all the future will be lost,” Ciais cautioned.But he’s worried the Earth might be on track to warm more rapidly than some scientists — and world leaders — expect. Many climate models don’t account for an increasingly rapid breakdown of Earth’s natural ecosystems, accelerated by wildfires, droughts, pests and other climate-related disasters.Meanwhile, studies have found that fossil fuel emissions also reached a record high in 2024. Those emissions can’t account for last year’s CO₂ surge all on their own. But they’re part of the puzzle, and a major indicator that the world is not tackling global warming quickly enough to meet the Paris Agreement’s climate goals.“The policy goals say, well, we still have some time to reach 2 degrees,” Ciais said. “But all these predictions are based on the fact that the carbon absorption will stay good.”Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2025. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.

0 Комментарии

0 Поделились

22 Просмотры