ARSTECHNICA.COM

“You wouldn’t steal a car” anti-piracy campaign may have used pirated fonts

Type off the back of a truck

“You wouldn’t steal a car” anti-piracy campaign may have used pirated fonts

Digging into archived site points to use of questionable text styling.

Kevin Purdy

–

Apr 27, 2025 7:15 am

|

14

Credit:

Aurich Lawson

Credit:

Aurich Lawson

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Learn more

You wouldn't steal a car, right? So you shouldn't pirate a movie, either.

That was the gist of the infamous "You Wouldn't Steal a Car" anti-piracy campaign from the Motion Picture Association of America during the mid-2000s. But questions are now being asked about just how carefully the MPAA followed its own anti-piracy principles when designing the campaign. Specifically: Did the MPAA rip off a key font?

The answer to that question is, like many matters involving typefaces, fonts, and copyright, somewhat complicated.

The rich potential for hypocrisy

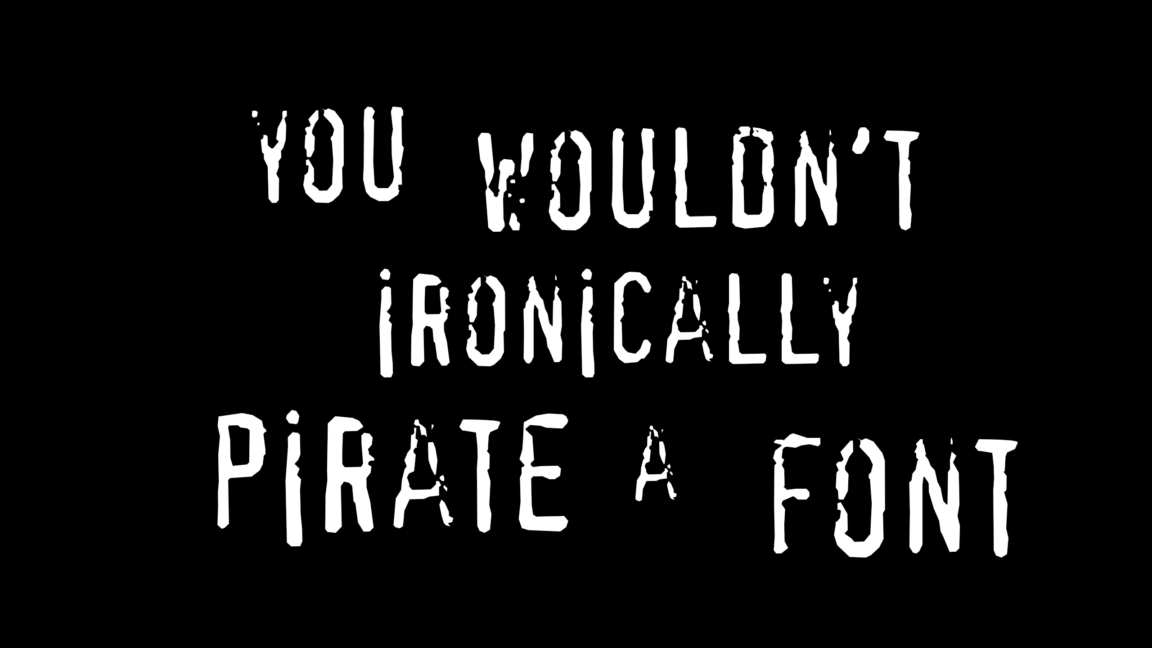

The anti-piracy campaign was … not exactly subtle. Its spots ran before movies in theaters and on home media from 2004–2008. One shows a teen girl clicking a big green "Download" button on a website promising "Feature Films"—but when she does so, large white text jumps onto a black backdrop: "You wouldn't steal a car." The text looks like it was applied with spray paint and a stencil.

"Piracy. It's a crime," i.e., "You wouldn't steal a car," aka "You wouldn't download a car."

What font is this? The site Fonts in Use suggests it was FF Confidential, designed by Just van Rossum in 1992.

Melissa Lewis, a reporter at the Center for Investigative Reporting, noticed Fonts in Use's identification, and she remembered that noted "computer person" Parker Higgins had been digging into the "very similar (font) Xband Rough." Lewis contacted van Rossum, who confirmed that Xband Rough was a clone of FF Confidential. "It's just been around forever and is ubiquitous," Lewis writes.

Picking up on these inquiries, a tinkerer going by the handle "Rib" then dug into a PDF from the anti-piracy campaign's archived website. A tool called FontForge indicated that the notable "spray-painted" font used in the PDF was, in fact, XBand Rough.

Van Rossum—who is the brother of Guido van Rossum, creator of the Python programming language—told TorrentFreak that he knew the anti-piracy campaign had used his font, and he knew that the Xband Rough clone existed. He did not know that the industry group had used the knock-off version in its campaign, but he found it "hilarious." Van Rossum, reached for comment by Ars, declined to comment.

How widespread was the use of Xband Rough? Is there a chance that the creator of the PDF in question, working separately from the other creators of the awareness campaign video and website, used Xband Rough to approximate FF Confidential in just this single document? Perhaps. Without access to the master files for the anti-piracy campaign, it's difficult to say whether more than just a few supplemental materials were using fonts with dubious histories.

What is font “piracy,” exactly?

The very first design patent issued in the US was given to George Bruce in 1842, for a new typeface. This would not happen very often in the many years to come.

Credit:

U.S. Trademark and Patent Office

The very first design patent issued in the US was given to George Bruce in 1842, for a new typeface. This would not happen very often in the many years to come.

Credit:

U.S. Trademark and Patent Office

A typeface is the design or style of letters and characters (say, Helvetica), while a font is one application and variation of that design or style (say, Helvetica Rounded Bold 14pt). In the US, a "Typeface as typeface" and "mere variations of typographic ornamentation" are not subject to copyright, as was decided in 1978's Eltra Corp. v. Ringer. Before that, typeface protections had been considered in a 1975 congressional hearing but were not met with enthusiasm.

James Aquilina, an intellectual property attorney and partner at the Quarles law firm in Washington, DC, said that most typefaces have difficulty overcoming the originality requirement necessary for copyright protection. "They're so close to other typefaces, it's hard to show originality," he said.

But a font, or specifically a "font file" on a computer that makes displaying a certain typeface possible, can be protected by US copyright because it is something like software. "There is more going on there; there is likely some source code for a [copyright] applicant to rely on," Aquilina said. "The copyright could reside in the output of that software code."

FF Confidential was first published by the FontFont foundry in 1992. FontFont was acquired by industry giant Monotype Imaging in 2014. At Monotype's online store, FF Confidential carries a trademark symbol and is noted to be "registered in the US Patent and Trademark Office and may be registered in certain other jurisdictions."

In the UK, where the anti-piracy trailers also ran, the question of copyright protection is more complicated, though copyright law generally protects typefaces for 25 years after first publication. In Germany, where original publisher FontFont was headquartered, typefaces are protected for the first 10 years, then an additional 15 years if a rightsholder pays a fee, providing a total of 25 years of protection.

Aquilina, who was speaking generally and not on the specifics of the anti-piracy campaign and its font use, said that using a font from a free source, with an "effectively implied license to use it," could be "a good defense," though "not a complete defense." Typically, a rightsholder would go after websites distributing copies of their font, not after users of the end product.

Fonts used commercially that happen to be exact copies of existing and copyrighted fonts are "fairly common," Aquilina said, "simply because of the popularity of certain fonts and a desire to use them, to create a certain aesthetic." But, he said, there is "a very small percentage that could be, or are, litigated." Even with software licenses at issue, a type foundry faces an uphill battle, as witnessed in the battle over Shake Shack's typography (paywalled).

Still missing: the source of XBand Rough

A few glyphs from FF Confidential, the font that was not used on some anti-piracy materials, even if it sure looked like that.

Credit:

MyFonts/MonotType

A few glyphs from FF Confidential, the font that was not used on some anti-piracy materials, even if it sure looked like that.

Credit:

MyFonts/MonotType

So where did Xband Rough come from?

The styling of the font name, "XBAND Rough" with the first noun in all-caps, calls to mind the early online gaming network XBAND, launched in 1994 and discontinued in 1997. In some XBand packages, a similar "rough" style can be seen on the lettering. The PDF sleuth, Rib, noted that XBAND Rough "came out four years after the original" (about 1996) and was "near-identical, except for the price."

Another Bluesky user suggests "a plausible explanation" for the font, suggesting that Xband may have licensed FF Confidential and then given it the internal name "Xband Rough." A copy of the font with that name could have been extracted from some Xband material and then "started floating around the Internet uncredited." In the end, though, the real answer is unclear.

We contacted the Motion Picture Association (now just the MPA, sans "of America"), but they declined to comment.

The original "You Wouldn't Steal a Car" campaign was simple to the point of being simplistic. IP law isn't really like "stealing a car" in many cases—as has made clearly once again by the recent Xband Rough investigation.

Kevin Purdy

Senior Technology Reporter

Kevin Purdy

Senior Technology Reporter

Kevin is a senior technology reporter at Ars Technica, covering open-source software, PC gaming, home automation, repairability, e-bikes, and tech history. He has previously worked at Lifehacker, Wirecutter, iFixit, and Carbon Switch.

14 Comments

0 Comments

0 Shares

52 Views