WWW.SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

Scientists in Australia Mapped the Genome of an Endangered Frog Species in an Effort to Save It

Scientists in Australia Mapped the Genome of an Endangered Frog Species in an Effort to Save It

A deadly fungus threatens the southern corroboree frog, which needs a lot of help to survive

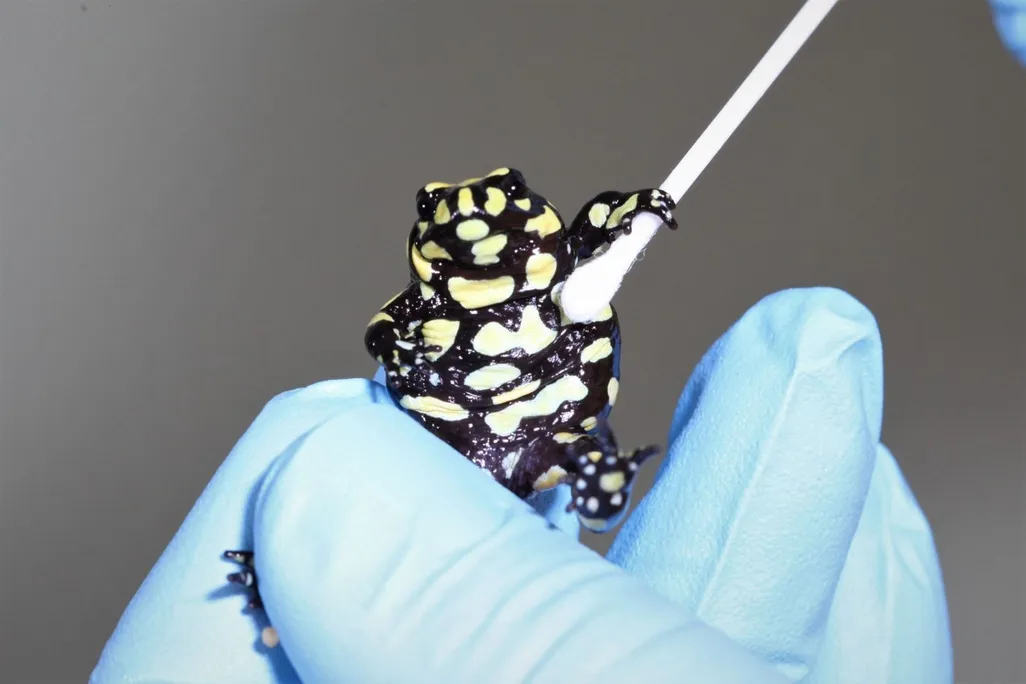

A researcher swabs a frog.

Corey Doughty

The southern corroboree frog is an iconic species in Australia. The tiny frog is known for the striking yellow and black markings that cover its body, which warn predators of its poisonous skin. The frog is also one of the most threatened amphibians in the country—with its primary threat being chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by the chytrid fungus.

Now, researchers have sequenced the frog’s entire genome for the first time, with the hope that their work can help save the animal. Their research was published in the journal Wellcome Open Research last week.

“They’re quite unique frogs. They belong to this ancient family of frogs that’s only found in Australia,” says Tiffany Kosch, a conservation biologist at the University of Melbourne and lead author of the study, to Petra Stock at the Guardian. “They’re about 100 million years old”

Along with other frog species around the world, the corroboree frog began to mysteriously die off in the 1980s. A decade later, Australian scientists identified the chytrid fungus as the main culprit.

Today, less than 50 individual southern corroboree frogs live in the wild. Ever since learning of the decimation of frogs due to the fungus, Kosch knew that she “wanted to be part of the solution,” she writes in a statement.

Mapping the frog’s genome was no easy feat. The entire project took ten years of work across multiple institutions. “Seeing the first assembled genome data was an incredible moment for me—after years of effort, we finally had a complete genetic blueprint of this iconic species,” Kosch writes in a statement.

The frogs have large genomes three times the size of humans

Tiffany Kosch

“This project is a testament to the power of collaboration, persistence and scientific innovation,” she adds. Kosch and her team worked with the Vertebrate Genomes Project at Rockefeller University and the New South Wales Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

“We discovered that southern corroboree frogs have remarkably large genomes—more than three times the size of the human genome,” Kosch explains in a statement. “A lot of other frogs in their family have much smaller genomes—including one of the smallest frog genomes on record,” she adds to the Guardian.

The scientists also discovered that 80 percent of the frog’s genome is made up of non-coding DNA, genetic material that doesn’t directly code for protein. The research team is still working on understanding what that means for both the corroboree and other frog species.

Simon Clulow, a conservation ecologist at the University of Canberra who was not involved in the study, tells the Guardian that having the full genome sequence will make understanding and helping the frog much easier. For example, researchers could work on identifying resistant genetic traits to help protect frogs against the fungus.

The next phase of the work—made possible by deciphering the genome—will involve determining what causes the frog’s susceptibility to the chytrid fungus.

“The hope is that work with the southern corroboree frog could be used as a proof-of-concept for other frogs threatened by the chytrid fungus, and potentially other species threatened by climate change,” adds Kosch to the Guardian. “The genome is really just the first step in helping us get there.”

Nicki Mitchell, a zoologist at the University of Western Australia not involved in the work, adds that more funding for biodiversity is needed to help endangered species in Australia. “The species, in some ways, is a symbol of the twin crises that we’re facing as a globe, of climate change and biodiversity loss,” she tells the Guardian.

For now, Kosch and her team will keep working on using the completed genome to uncover new information about the frog. “Our ultimate goal is to translate these findings into real-world conservation action, helping to secure a future for this remarkable species in the wild,” she writes.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.