ARSTECHNICA.COM

Heartbreaking video shows deadly risk of skipping measles vaccine

Tragically preventable

Heartbreaking video shows deadly risk of skipping measles vaccine

SSPE is rare but tragic—more so because it's completely vaccine-preventable.

Beth Mole

–

May 5, 2025 7:50 pm

|

34

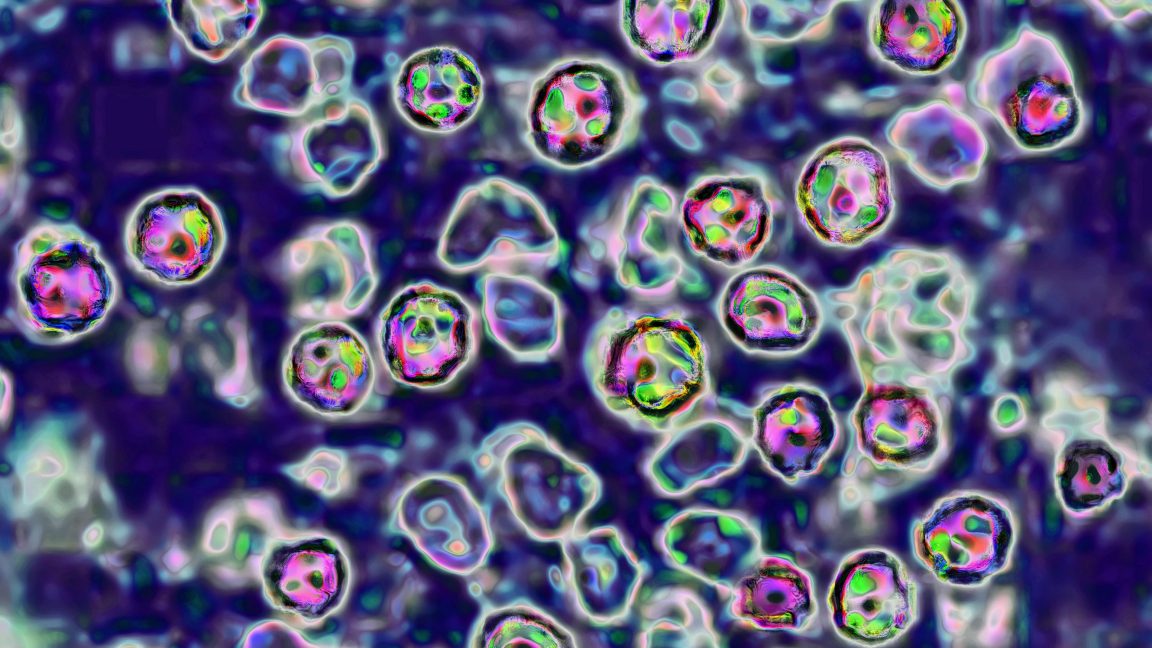

A brightly colored transmission microscope image of measles viruses.

Credit:

Getty | BSIP

A brightly colored transmission microscope image of measles viruses.

Credit:

Getty | BSIP

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Learn more

In a hard-to-watch video, a healthy-looking 4-year-old boy lies on a bed as doctors lift his eyelids to watch his big brown eyes erratically swirl and roll backward. His head jerks, and his little limbs weakly twitch and spasm. A small bit of foam pushes past his lips.

The video, captured by neurologists in India and published today in JAMA Neurology, shows what it looks like when the measles virus is allowed to ravage a child's brain. (The video can be viewed here.)

The boy was never vaccinated and developed a rare complication from measles called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). The condition occurs when the measles virus quietly sneaks into the central nervous system. It often lurks for years after an initial infection before it begins wreaking havoc, triggering damaging inflammation, destroying neurons, and causing brain lesions.

SSPE is almost always fatal, and there is no treatment for it. After the video was taken, the boy continued to deteriorate. He will almost certainly die. His doctors captured the video with permission from the boy's father and a critical message:

"Herein, we emphasize the importance of measles vaccination for children, as SSPE is typically fatal and yet also entirely preventable by vaccination."

The poignant video and message could not come at a more critical time. Measles has resurged globally in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it's having a particularly notable revival in the US, where vaccination rates have slipped nationwide. Many American communities have immunization rates below the threshold needed for herd immunity, and the country is currently seeing the largest outbreak in over a quarter-century. Modeling suggests that measles will once again become endemic. Meanwhile, the country's top health official, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is an unswerving anti-vaccine advocate with a long history of spreading dangerous misinformation, which may spur vaccination rates to fall further.

Measles risks

The video of SSPE is a clear reminder of the devastation that measles can cause, and the risks parents take by not getting their children vaccinated. An uncomplicated measles infection causes intense fevers and a thoroughly miserable rash for several days. But complications are not that rare. In the US, 20 percent of children with measles will be hospitalized. Ten percent will develop diarrhea and/or an ear infection, which has the potential to cause hearing loss. One in 20 will develop pneumonia, and 1 in 1,000 will develop brain swelling—up to 3 in 1,000 will die of these respiratory and neurologic complications.

Even when a child makes it through the acute phase of the infection, the risks aren't over. The measles virus can wipe out the immune system's memory of how to fight other germs—a phenomenon called "immune amnesia." This leaves children vulnerable to secondary infections for approximately two to three years after an infection.

Then, there's SSPE. The neurologic condition is considered rare and is poorly understood. Researchers estimate that there are up to 11 SSPE cases per 100,000 measles cases. However, the risk of SSPE is higher for children who get infected before the age of 5, in which case it's 18 per 100,000 measles cases. SSPE doesn't develop immediately, it can take months to many years after an acute infection—the average is between seven to ten years post-infection. Experts don't entirely understand how it happens. Some evidence suggests that abnormal immune responses or mutations that the virus may acquire once inside neurons may play a role. What is clear is that the risk from measles far outweighs any risk posed by vaccination.

Once SSPE develops, it moves through progressive stages, starting with mood swings, personality changes, depression, lethargy, and possibly fever and headache. This first stage can last up to six months. Then stage two involves jerking movement, spasms, loss of vision, dementia, and seizures. The third stage sees the jerking turn to writhing and rigidity. In the last stage, autonomic failure sets in—heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing become unregulated. Then comes coma and death. About 95 percent of SSPE cases are fatal.

Tragic ending

In the boy's case, his parents don't know when he was infected with measles. When doctors saw him, his parents recalled that in the prior six months, he had started having jerky movements, falls, and progressive cognitive decline. Before that, he had been healthy at birth and had been hitting all of his developmental milestones.

In some ways, his decline was an unmistakable case of SSPE. Imaging showed lesions in his brain. He had elevated anti-measles antibodies in his cerebrospinal fluid. An electroencephalography (EEG) showed brain waves consistent with SSPE. Then, of course, there were the jerking motions and the cognitive decline.

What stood out, though, was his rolling and swirling eyes. Vision problems are not uncommon with SSPE—sometimes the condition damages the retina and/or optic nerve. Some patients develop complete vision loss. But, in the boy's case, he developed rapid, repetitive, erratic, multidirectional eye movements, a condition called opsoclonus. Doctors often see it in brain cancer patients, but brain inflammation from some infections can also cause the movements. Experts hypothesize that the root cause is a loss of specialized neurons involved in coordinated movement, namely Purkinje cells and omnipause cells.

The boy's neurologists believe this is the first time opsoclonus associated with SSPE has been caught on video. They treated the boy with an antiviral drug and drugs to reduce convulsions, but his condition continued to worsen.

Beth Mole

Senior Health Reporter

Beth Mole

Senior Health Reporter

Beth is Ars Technica’s Senior Health Reporter. Beth has a Ph.D. in microbiology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and attended the Science Communication program at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She specializes in covering infectious diseases, public health, and microbes.

34 Comments