WWW.SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

Locals Thought These Shipwrecks Had Belonged to Pirates. They Turned Out to Be 300-Year-Old Danish Slave Ships

Cool Finds

Locals Thought These Shipwrecks Had Belonged to Pirates. They Turned Out to Be 300-Year-Old Danish Slave Ships

The two vessels had been trafficking hundreds of enslaved Africans when a navigational error led them astray. They sank off the coast of Costa Rica in the 18th century

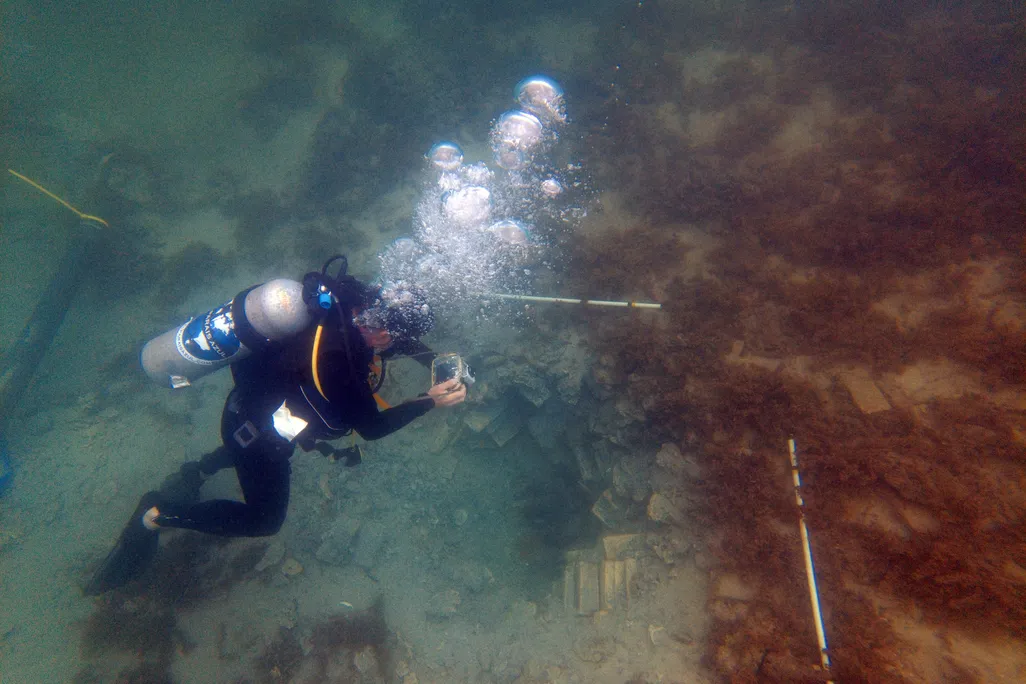

Marine archeologist Andreas Kallmeyer Bloch documents the shipwreck.

John Fhær Engedal Nissen / The National Museum of Denmark

Archaeologists have confirmed that two shipwrecks off the coast of Costa Rica are the remains of the Fridericus Quartus and Christianus Quintus, two Danish slave ships that have been missing since they sank in the 18th century.

Located in shallow waters near Costa Rica’s Cahuita National Park, the wrecks were long thought to belong to pirate ships, according to local legend. Instead, researchers investigating the ships’ timbers and cargoes last month confirmed that they sank while carrying around 690 enslaved Africans.

“The analyses are very convincing, and we no longer have any doubts that these are the wrecks of the two Danish slave ships,” David Gregory, a marine archaeologist from the National Museum of Denmark, says in a statement.

The archaeologists used dendrochronology—the study of tree rings—to establish that the timbers of the ship were harvested from oak trees sometime between 1690 and 1695. They also found that the oak trees were located in the western Baltic Sea, a region that includes northeastern Germany, southern Sweden and Denmark.

Gregory notes that one set of timbers was “charred and sooty from a fire. This fits perfectly with the historical accounts stating that one of the ships burnt,” per the statement.

The ships’ cargoes also helped the researchers confirm their Danish origin. A stash of yellow bricks matched the color and measurements of Flensburg bricks, a variety that was manufactured from Danish clay and exported to build forts and sugar plantations in Danish colonies. Chemical analysis of the bricks revealed that the clay came from one of two production sites on the Flensburg Fjord.The archaeologists confirmed that a series of Dutch-made clay pipes found aboard the ships were produced just before the shipwrecks took place in 1710. As the statement notes, clay pipes were “rarely used for more than five years.”

Although locals had long been aware of the shipwrecks, they were first documented in the 1970s, per the Tico Times. After archaeology students from East Carolina University discovered the Flensburg bricks in 2015, the shipwrecks sparked renewed academic interest.

“It’s been a long process, and I’ve come close to giving up along the way, but this is undoubtedly the craziest archaeological excavation I’ve yet been part of,” Andreas Kallmeyer Bloch, a marine archaeologist and curator at the Danish National Museum, says in the statement.

The discovery offers significant insight into both Danish and Costa Rican history—as well as the stories of slavery that entangle them.

The Fridericus Quartus and Christianus Quintus departed Copenhagen in December 1708. They stopped in Ghana, where they picked up hundreds of enslaved Africans and began sailing across the Atlantic Ocean to the island of St. Thomas.

A “horrible” navigational error led the ships far past their destination and into shallow waters off Costa Rica, where they ran aground on reefs, as Bloch tells CNN’s Amarachi Orie.

By some accounts, mutiny swelled among the ships’ crews. One ship caught fire, and the other was likewise abandoned when its anchor cable was cut. Of the nearly 700 enslaved Africans whom the Danish brought to Costa Rica, roughly 100 were recaptured and sent to work on cacao plantations in nearby Matina, per the Tico Times.

Marine archaeologist David Gregory documents and samples Flensburg bricks.

John Fhær Engedal Nissen / The National Museum of Denmark

These new findings suggest that nearly 600 Africans were left on the beaches of Costa Rica, contributing to an Afro-Costa Rican population in the region “100 years before it was registered in official history,” Maria Suarez Toro, a journalist, activist and founder of the underwater archaeology-focused Ambassadors of the Sea Community Diving Center, tells CNN.

The archaeologists hope their research can provide the local population with a more comprehensive understanding of their heritage, which has long been obscured by the tragedies of the slave trade.

For instance, Celia Ortiz, a resident of Cartago, Costa Rica, can trace her ancestry back to Miguel Maroto, one of the enslaved men aboard the Danish ships, according to CNN. For Ortiz and her 103-year-old mother, learning the true history of their ancestry “brought new light to our lives.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.