WWW.SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

Humans Have Seen Only 0.001 Percent of the World's Deep Seas, Leaving Most of the Planet a Vast Mystery

Humans Have Seen Only 0.001 Percent of the World’s Deep Seas, Leaving Most of the Planet a Vast Mystery

Researchers argue that expanding deep-sea exploration is vital to understanding and managing these marine habitats

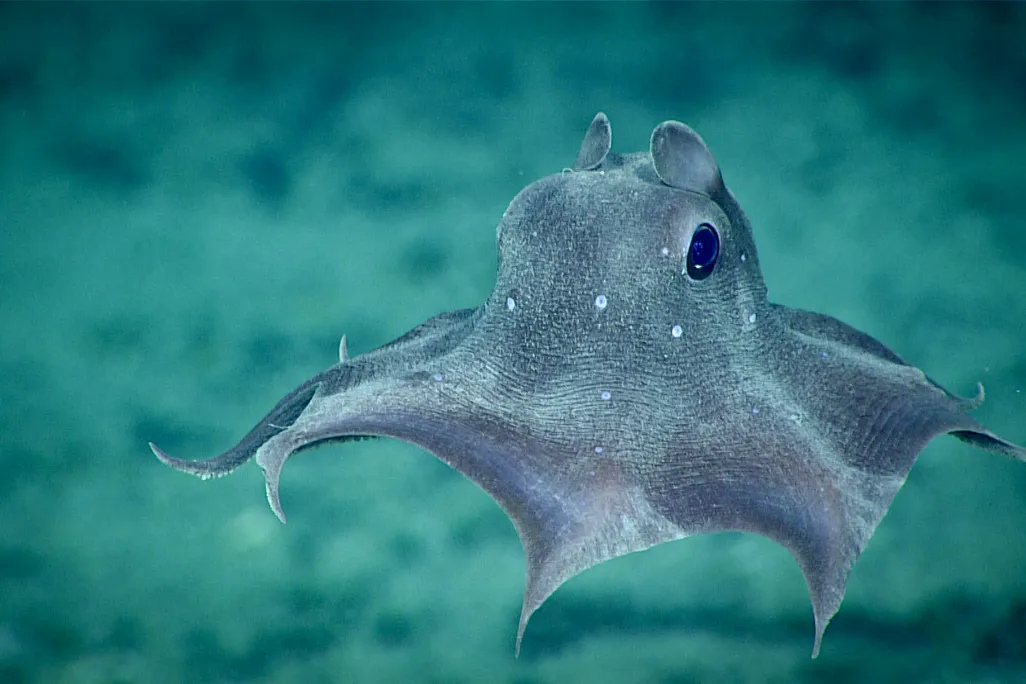

Dumbo octopuses, like the Opisthoteuthis agassizii seen here during a 2019 dive, are the deepest-living group of octopuses known.

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration

Humans have been exploring the deep seas, which make up 66 percent of our planet’s surface, for decades. But a new study reveals just how far we have left to go in understanding the mysterious seascape.

Researchers from the nonprofit Ocean Discovery League estimate scientists have directly observed less than 0.001 percent of the Earth’s deep seafloor—totaling an area that’s approximately equivalent to the size of Rhode Island. That means 99.999 percent of the ocean floor remains unexplored. Their work is detailed in a new study published last week in the journal Science Advances.

The deep ocean describes regions more than 656 feet below the surface of the water. While these marine areas might feel inconsequential to daily life, they’re critical to environmental processes such as oxygen production and climate regulation, and they host entire ecosystems.

It was only in 1977 that researchers discovered hydrothermal vents. “Now we know that you can have entire ecosystems that originate in darkness and feed off this hot, mineral-rich water coming up out of the seafloor,” says lead study author Katy Croff Bell to New Scientist’s Madeleine Cuff.

The problem facing this field, however, is that deep sea exploration is expensive and laborious. Bell tells the New York Times’ Rebecca Dzombak that exploring 0.39 square miles of deep seafloor can cost between $2 million and $20 million. And “when you’re down there with a remotely operated vehicle or other sort of deep-submergence vehicle, you can only see a very tiny bit of the deep-sea floor at any one time,” she tells NPR’s Nell Greenfieldboyce. Four or five years ago, she began to ask: “Well, how much have we actually seen?”

Deep-sea diving activity has been concentrated in a small number of locations, including Monterey Bay and Hawaii in the United States, Suruga and Sagami Bays in Japan, and New Zealand.

Ocean Discovery League

To answer this question, Bell and her colleagues collected records from around 44,000 deep-sea dives in the waters of 120 different countries since 1958. Their analysis revealed humans had observed an incredibly miniscule amount of the deep seafloor. Even when taking into account that some dive records aren’t public, their estimates remain at less than 0.01 percent. To make matters worse, the visuals captured before 1980—which add up to almost 30 percent of all visual observations—are mostly poor-quality, black-and-white images.

“As we face accelerated threats to the deep ocean—from climate change to potential mining and resource exploitation—this limited exploration of such a vast region becomes a critical problem for both science and policy,” Bell explains in a statement.

Additionally, more than 65 percent of the visual observations were conducted within 200 nautical miles of the United States, New Zealand and Japan. These three countries, along with France and Germany, are behind 97 percent of all deep-sea submergence observations.

These limitations are “problematic when attempting to characterize, understand and manage a global ocean,” study co-author Susan Poulton tells Gizmodo’s Isaac Schultz. “Imagine trying to tell the story of critical environments like the African savanna or the Amazon rainforest using only satellite imagery and DNA samples without ever seeing what lived there.”

The concentration of known deep-sea dives with visual observations in exclusive economic zones in the United States

Ocean Discovery League

The researchers also revealed that certain deep-sea topographical features, like canyons and ridges, have attracted much more scientific attention than abyssal plains and seamounts. Their work was published less than two weeks after President Trump signed an executive order to accelerate the exploitation of deep-sea resources, such as through mining.

Ultimately, the study appeals for more extensive exploration of the deep oceans and the identification of target areas for future research that will offer a more representative view into the global ocean floor. Scientists suggest supporting the development of affordable deep-sea tools to increase research access in low- and middle-income countries.

“If I were a billionaire philanthropist and I wanted to make a real dent in exploring the ocean,” Jon Copley, a marine biologist at the University of Southampton in England who wasn’t involved in the study, tells NPR, “then rather than building a kind of superyacht research ship, I would fully back the development and growth of these kinds of low-cost platforms.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.