ARSTECHNICA.COM

A telltale toilet reveals lost site shown in Bayeux Tapestry

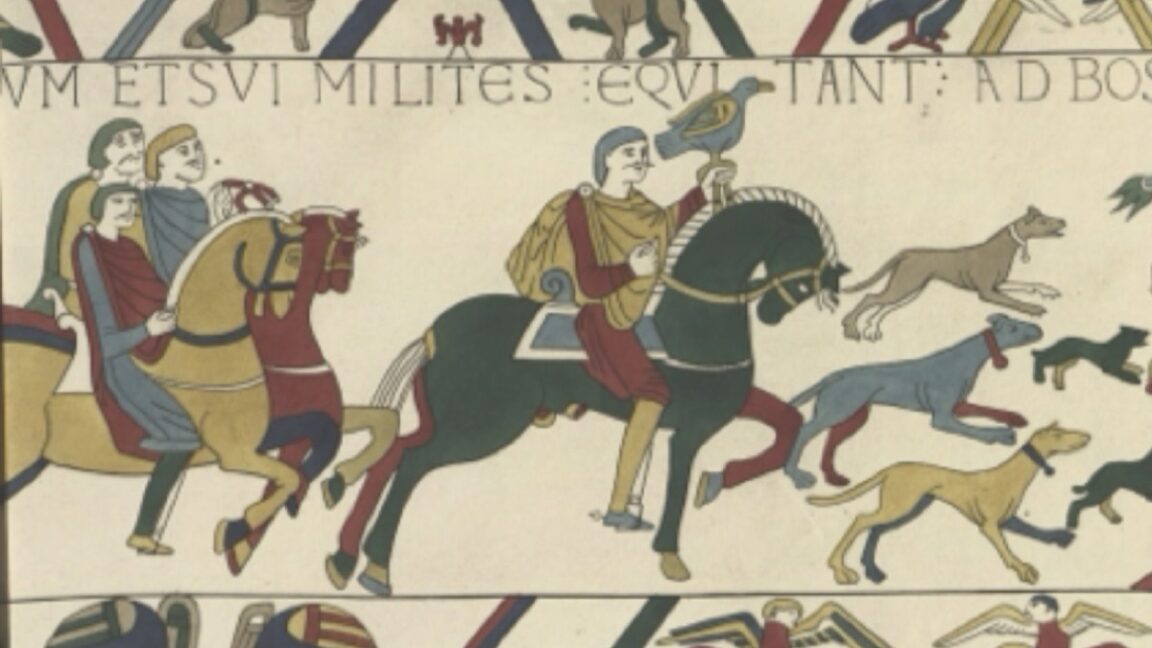

the telltale toilet A telltale toilet reveals lost site shown in Bayeux Tapestry A house in England is most likely the site of a lost residence of Harold II, the last Anglo-Saxon King of England. Jennifer Ouellette Jan 28, 2025 1:56 pm | 4 Credit: The Society of Antiquaries of London Credit: The Society of Antiquaries of London Story textSizeSmallStandardLargeWidth *StandardWideLinksStandardOrange* Subscribers only Learn moreThe Bayeux Tapestry famously depicts the events leading up to the 1066 Norman Conquest of England, in which William the Conqueror defeated Harold II, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, at the Battle of Hastings. Two scenes in particular show King Harold feasting in an extravagant hall in a village called Bosham. Archaeologists think they have now located the site of that feast, concluding that it was the king's own home, according to a new paper published in The Antiquaries Journal.The Norman Conquest saw a new ruling class supplant an English aristocracy that has left little in the way of physical remains, which makes the discovery at Bosham hugely significant," said co-author Oliver Creighton of the University of Exeter. "We have found an Anglo-Saxon show-home. The findings are part of an ongoing project called "Where Power Lies," intended to assess archaeological evidence for aristocratic centers across England from the pre-Norman period.Scholars believe the Bayeux Tapestry dates back to the 11th century and was likely created just a few years after the Battle of Hastings, mostly likely commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux (although there is still considerable debate over alternative theories). It's technically not a tapestry, since it's not woven but embroidered on linen using wool yarn of various colors. There are 58 individual scenes spanning 230 feet (nearly 70 meters) in length and 20 inches (50 cm) in height. Latin text provides context for the imagery. Among the historical events depicted is the appearance of what is now known as Halley's Comet, used here as a harbinger of the coming Norman invasion.Now housed in the Muse de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Normandy, France, the Bayeux Tapestry is considered a rare example of secular Romanesque art, similar in its narrative style to a cartoon strip. Indeed, cartoonist Scott McCloud used it as an example of this kind of sequential narrative in his 1994 book, Understanding Comics. Parts of the tapestry have been featured in the opening credits of several films as well as the S2 opening credits of House of the Dragon, which incorporated an animated sequence in embroidery inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry.Seats of power The Bayeux Tapestry, showing King Harold riding to Bosham, where he attends church and feasts in a hall, before departing for France. The Society of Antiquaries of London The Bayeux Tapestry, showing King Harold riding to Bosham, where he attends church and feasts in a hall, before departing for France. The Society of Antiquaries of London Part of the garden ruin at Bosham, confirmed as a medieval building by recent research. Newcastle University Part of the garden ruin at Bosham, confirmed as a medieval building by recent research. Newcastle University Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, looking east. Newcastle University Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, looking east. Newcastle University Part of the garden ruin at Bosham, confirmed as a medieval building by recent research. Newcastle University Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, looking east. Newcastle University According to Creighton and his co-authors, there has been quite a lot of research on castles, which dominated aristocratic sites in England after the Norman Conquest. That event "persists as a deep schism that continues to be seen as the watershed moment after which elites finally tapped into the European mainstream of castle construction," they wrote. The study of residences (or "lordly enclaves") has been more peripheral, yet the authors argue that up until 1066, aristocrats and rulers like King Harold invested heavily in residences, often co-located with churches and chapels.The "Where Power Lies" project employed a wide range of research methodologyincluding perusing old maps and records, a re-analysis of past excavations, geophysics, ground-penetrating radar (GPR), and photogrammatic modelingto define the signatures of such enclaves and map them into a single geographic information database (GIS). The project has identified seven such "lordly centers," two of which are discussed in the current paper: an early medieval enclosure at Hornby in North Yorkshire and Bosham in West Sussex.It has long been suspected that one particular manor house in Bosham (now a private residence) stands on the site of what was once King Harold's residence. Per the authors, the original residence was clearly connected with Holy Trinity Church just to the south, parts of which date back to the 11th century, as evidenced by the posthole remains of what was once a bridge or causeway. More evidence can be found in a structure known as the "garden ruin," little of which survives above groundand even that was heavily overgrown. GPR data showed buried features that would have been the eastern wall of King Harold's lordly enclave.The biggest clue was the discovery in 2006 of a latrine within the remains of a large timber building. Its significance was not recognized at the time, but archaeologists have since determined that high-status homes began integrating latrines in the 10th century, so the structure was most likely part of King Harold's residence. Co-author Duncan Wright of Newcastle University believes this "Anglo-Saxon en suite," along with all the other evidence, proves "beyond all reasonable doubt that we have here the location of Harold Godwinson's private power center, the one famously depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry."DOI: The Antiquaries Journal, 2025. 10.1017/S0003581524000350 (About DOIs).Jennifer OuelletteSenior WriterJennifer OuelletteSenior Writer Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban. 4 Comments