Elon Musk's 'Fork in the Road' Is Really a Dead End

www.scientificamerican.com

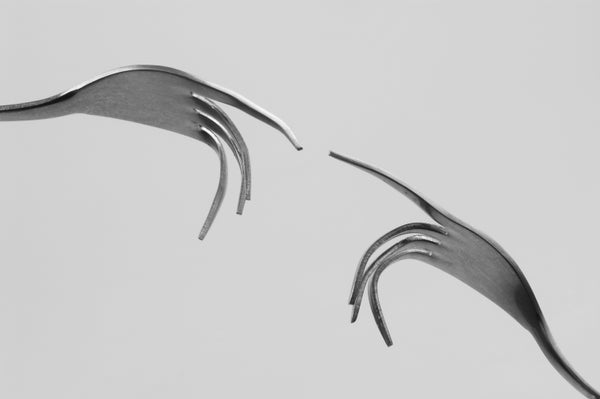

OpinionFebruary 6, 20255 min readWhy Elon Musk's 'Fork in the Road' Is Really a Dead EndElon Musks Fork in the Road isnt just a sculptureits a monument to the tech worlds obsession with civilizational survival, which has its roots in the search for extraterrestrial intelligenceBy Rebecca Charbonneau edited by Dan VerganoUnlike the Sistine Chapel-esque utensils in this stock photo, Elon Musk's Fork in the Road seems more about deliberately misreading history than gaining any sort of divine inspiration. Lebazele/Getty ImagesOn December 7, 2024, Elon Musk shared an image of artwork he had commissioned for Tesla HQ titled A Fork in the Road. A colossal piece of flatware planted at the intersection of three roads, it is not subtleit is, quite literally, a fork in the road.The sculpture returned to headlines less than two months later when the Trump administration sent out an e-mail with the subject line Fork in the Road, echoing an earlier e-mail Musk had sent to Twitter employees with the same title, both urging mass resignations. News reports suggest that Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) were behind the phrases resurgence.The fork in the road theme hints at a trend in the tech industry: a preoccupation with existential threats, which finds resonance in cold warera ideas. In this simplistic binary, the future of humanity can only follow two starkly divergent paths: one notionally leading to nearly limitless prosperity on Earth and beyond, the other leading nowhere besides the collapse of our global civilization and ultimately human extinction. Proponents of this survivalist mindset see it as justifying particular programs of technological escalation at any cost, framing the future as a desperate race against catastrophe rather than a space for multiple thriving possibilities.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.This existential anxiety bubbled to the surface in his December 7 post, when Musk captioned the photo of the sculpture with a cryptic statement: Had to make sure that civilization took the path most likely to pass the Fermi Great Filters.Musks reference to the Fermi Great Filters combines two distinct but related ideas that have become popular in technology circles: the Fermi paradox and the concept of existential filters. The paradox originated in 1950, during a lunchtime conversation at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Enrico Fermi, a prominent nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, and his colleagues were discussing UFOs, perhaps prompted by the 1947 flying disc craze that had shaken the country just a few years earlier. Given the vast number of potentially habitable planets and myriad plausible methods for interstellar communication or travel, they wondered why humans hadnt yet encountered evidence of alien civilizations. Fermi famously summed up the dilemma in a single question: Where is everybody?The apocryphal story has transformed into a popular thought experiment. A common explanation for the apparent absence of extraterrestrial neighbors is what economist Robin Hanson termed the Great Filterthe idea that there exists a major obstacle preventing civilizations from reaching a stage at which they have the capability to send messages or crewed voyages to other star systems. The Great Filter may lie behind us, meaning life on Earth already beat the odds in overcoming some catastrophe, allowing our civilization to develop. Or else we might yet face some challenge thats hard to survive. Though the term itself is fairly new, it builds on cold warera concepts, particularly those tied to the Kardashev scalea framework developed in the 1960s that speculated on how extraterrestrial civilizations might progress.The Kardashev scale has become a key influence on some technologists. Proposed in 1964 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev, the scale classifies extraterrestrial civilizations based on their energy use: Type I civilizations harness all the energy available on their home planet; Type II civilizations capture the total energy output of their star; and Type III civilizations command energy on the scale of their entire galaxy. Musk has cited the Kardashev scale on X over a dozen times in the past year, often framing humanitys progress in terms of ascending it (He once wrote: Any self-respecting civilization should at least reach Kardashev Type II.). Originally a thought experiment, the scale is now often treated as a literal roadmapimplying a desirable, even inevitable, trajectory toward greater energy consumption and interstellar expansion.The cold war, which gave us both the Fermi paradox and the Kardashev scale, was defined by existential anxiety. Nuclear weapons ushered in the possibility of humanitys rapid self-destruction, and scientists were acutely aware of their enabling role in our species potential demise. This fear deeply influenced early SETI scientists, shaping their ideas about the civilizations they hoped to find in the galaxy. Often their imagined civilizations mirrored their own anxieties and aspirations.The Kardashev scales focus on energy consumption as the primary metric of advancement reflects a distinctly 20th-century worldview, one shaped by multiple overlapping technological revolutions. Kardashev developed his scale as part of a broader exploration of what extraterrestrial supercivilizations might look likecivilizations not unlike what in some appraisals the Soviet Union aspired to become, with its spacefaring ambitions, imperial reach and technological might. The scale was designed as a tool to help SETI scientists imagine the kinds of artificial signals such civilizations might produce. Kardashev was not an oracle or a prophet; he was a 30-year-old astronomer living behind the iron curtain, grappling with the possibilities of a future that, for him, seemed shaped by a heady blend of hope and fear.Existential anxiety has now also become pervasive in the tech world. It drives tech billionaires to invest in space programs, advocate for pronatalist policies to counter a feared population collapse, and promote multiplanetary settlement as an escape from climate change and other earthly woes. But while concerns about potential catastrophe are not without merit (though we have left the cold war behind us, there is no shortage of existential dilemmas facing our civilization), there is something reductive about framing the future in such all-or-nothing terms.Instead, we should be deeply skeptical of narratives that present civilizational progression as a one-way patha single road leading inevitably toward a predefined notion of progress, with all deviations resulting in doom. Is humanity really on the brink of either unprecedented flourishing or imminent doom, or is this just another iteration of an age-old tendency to view the present moment as uniquely dire? The Kardashev scale and the Great Filter are fascinating ideas that prompt us to consider the trajectory of civilizationshow they might harness energy, navigate existential risks and potentially reach beyond their home planets. But when they are treated as fixed, predictive frameworks, we risk reducing the complexity of human and extraterrestrial futures to a crude caricature of progress.But even if you accept a prescriptive interpretation of these cold warera ideas, why assume Musk and other tech-impresarios hold the key to becoming a Type II civilizationor avoiding the Great Filter? If we take the fork in the road at face value, what justifies the belief that they are the ones with the solution? Could they not equally be part of the problem, accelerating the very conditionsoligarchic control, systemic inequality and environmental degradationthat could lead to existential catastrophe? The irony is that their speculative ethos, when turned back on itself, reveals its own contradictions: a worldview that claims to safeguard humanitys future could just as easily be entrenching the very power structures that threaten it.That the uncritical embrace of cold war SETI theories is now justifying aggressive changes to the U.S. government and its workforce underscores their pervasive influence, but it also highlights their limitations. By framing humanitys challenges as simple engineering problems rather than complex systemic ones, technologists position themselves as decisive architects of our future, crafting grand visions that sidestep the messier, necessary work of social, political and collaborative change.The real fork in the road is not between survival and extinction, but between repeating the patterns of the past and embracing a richer vision of progressone that acknowledges multiple paths and possibilities, and rejects the notion that our fate must rest solely in the hands of tech billionaires.This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·44 Views