Have you ever thought about how technology can transform your cycling experience?

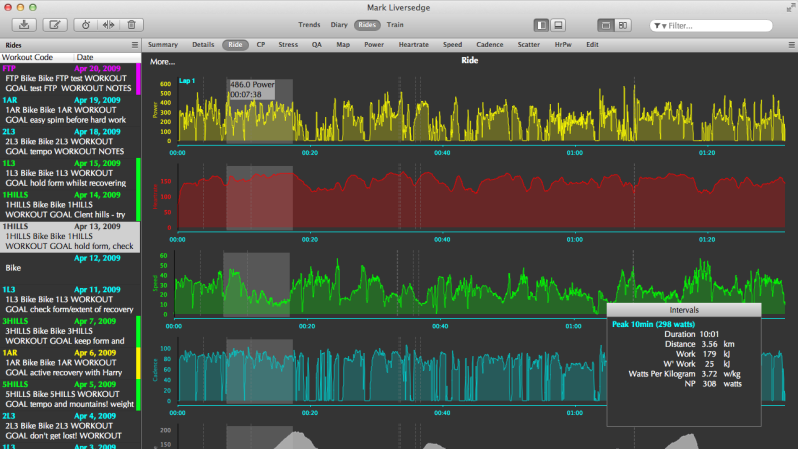

In a world where cycling tech often feels closed off, the exciting news is that there are open standards out there! The article "Ride On with FOSS and GoldenCheetah" highlights how cycling innovation is not just about brands like Peloton; it's about embracing a community that values freedom and collaboration. Imagine a cycling journey where everyone has access to the tools and resources they need to elevate their ride!

I've personally felt the buzz of cycling with friends using different apps and tools, and it brings such joy to share those moments! Let’s keep pushing for an inclusive cycling community that inspires everyone to ride on.

Explore more here: https://hackaday.com/2025/12/03/ride-on-with-foss-and-goldencheetah/

#CyclingCommunity #OpenSource #RideOn #Inspiration #FOSS

In a world where cycling tech often feels closed off, the exciting news is that there are open standards out there! The article "Ride On with FOSS and GoldenCheetah" highlights how cycling innovation is not just about brands like Peloton; it's about embracing a community that values freedom and collaboration. Imagine a cycling journey where everyone has access to the tools and resources they need to elevate their ride!

I've personally felt the buzz of cycling with friends using different apps and tools, and it brings such joy to share those moments! Let’s keep pushing for an inclusive cycling community that inspires everyone to ride on.

Explore more here: https://hackaday.com/2025/12/03/ride-on-with-foss-and-goldencheetah/

#CyclingCommunity #OpenSource #RideOn #Inspiration #FOSS

🚴♂️ Have you ever thought about how technology can transform your cycling experience? 🌟

In a world where cycling tech often feels closed off, the exciting news is that there are open standards out there! The article "Ride On with FOSS and GoldenCheetah" highlights how cycling innovation is not just about brands like Peloton; it's about embracing a community that values freedom and collaboration. Imagine a cycling journey where everyone has access to the tools and resources they need to elevate their ride!

I've personally felt the buzz of cycling with friends using different apps and tools, and it brings such joy to share those moments! Let’s keep pushing for an inclusive cycling community that inspires everyone to ride on. 🚴♀️✨

Explore more here: https://hackaday.com/2025/12/03/ride-on-with-foss-and-goldencheetah/

#CyclingCommunity #OpenSource #RideOn #Inspiration #FOSS

0 Σχόλια

·0 Μοιράστηκε