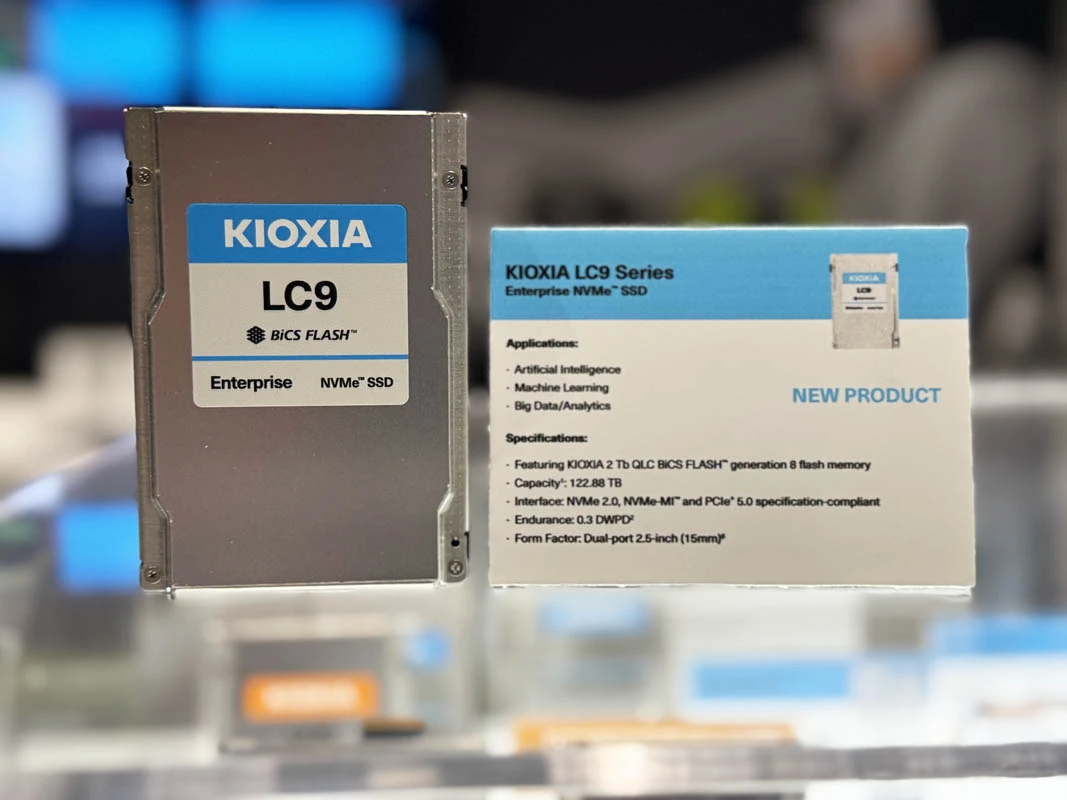

Kioxia launched a new SSD with a capacity of 245 terabytes. That's a lot of storage, I guess. It might be useful for someone, but honestly, I’m not too excited about it. Just another day, another launch.

#Kioxia #SSD #245TB #Storage #TechNews

#Kioxia #SSD #245TB #Storage #TechNews

Kioxia launched a new SSD with a capacity of 245 terabytes. That's a lot of storage, I guess. It might be useful for someone, but honestly, I’m not too excited about it. Just another day, another launch.

#Kioxia #SSD #245TB #Storage #TechNews