See Flannery O'Connor's Little-Known Visual Artworks That Had Been Collecting Dust in Storage

See Flannery O’Connor’s Little-Known Visual Artworks That Had Been Collecting Dust in Storage

From childhood cartoons to thoughtful self-portraits, the acclaimed Southern writer was always a keen observer of her surroundings

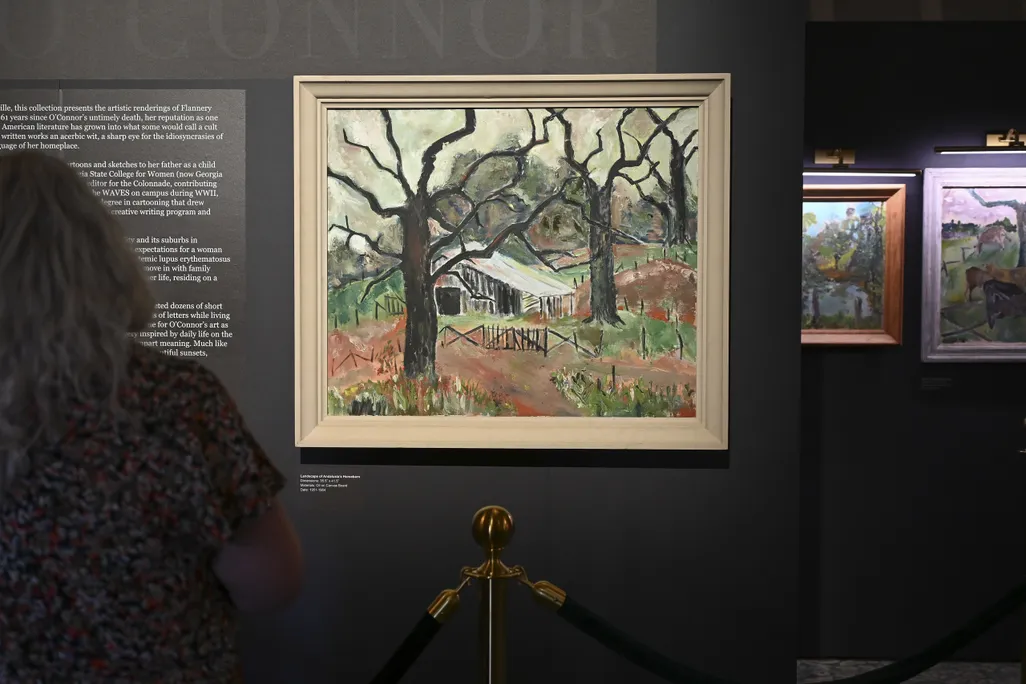

Many of O'Connor's artworks drew on the rural Southern surroudings of her family farm in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Georgia College & State University

“Any discipline can help your writing: logic, mathematics, theology, and of course and particularly drawing,” Flannery O’Connor wrote in an essay titled “The Nature and Aim of Fiction.” “Anything that helps you to see, anything that makes you look. The writer should never be ashamed of staring. There is nothing that doesn’t require his attention.”

As a writer, O’Connor took her own advice to heart. Across dozens of short stories and two novels published before her early death from lupus at age 39, she “refused to seek success by generating nostalgia for a mythologized past, instead sketching masterful portraits of the people she observed around her, in all their flaws and contradictions,” writes Smithsonian magazine’s Ellen Wexler.

But O’Connor didn’t just sketch people with her words. Long before she attended the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop or the Yaddo writers’ retreat in upstate New York, she drew cartoons and caricatures for her high school and college newspapers. Even as her writing career progressed, she never ceased turning her intense gaze toward visual art, from oil paintings to linoleum-block prints.

In celebration of her 100th birthday on March 25, 2025, Georgia College & State University, O’Connor’s alma mater, gathered 70 rare visual artworks from throughout her life for an exhibition called “Hidden Treasures” at Andalusia, the farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she spent the last 14 years of her life.

A cartoon from O'Connor's college days

Georgia College & State University

“Scholars continue to study Flannery, to research her, and to use her as a model in creative writing programs,” Katie Simon, a literary scholar and the interim executive director of the Flannery O’Connor Institute for the Humanities at GCSU, says in a statement. “She’s taught as an example of literature—but scholars are starting to look at her as a visual artist, as well. These paintings reveal that she never stopped creating visual art until her death.”

Many of the pieces in the exhibition are on public view for the first time. Although scholars and O’Connor fans were aware of her artworks, only “her family knew exactly where they were, which was a storage unit in town—storage unit behind the Cook Out,” a fast-food restaurant chain, as Andalusia curator Cassie Munnell tells Devon Zwald of Georgia Public Broadcasting.

Stashing O’Connor’s paintings, prints and drawings away in an obscure storage unit was no accident, however. The writer’s mother, Regina Cline O’Connor, and early trustees of her estate “weren’t sure if she would be rightly recognized as what she is: one of the greatest short story writers,” Farrell O’Gorman, a new trustee of the O’Connor estate, explains to the New York Times’ Walker Mimms. “I think they were worried that the paintings might somehow distract from her achievements as a writer.”

Born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1925, O’Connor grew up in Milledgeville and graduated from GCSU. While she prepared for a writing career up north, she was forced back to Andalusia in 1950, when she started developing symptoms of lupus.

The autoimmune disease meant that when O’Connor, a devout Catholic, wasn’t going to mass or tending to her peafowl, she spent much of her time on the first floor of the farmhouse—a state of immobility and isolation that honed her creative talents in prose and paint.

O'Connor's depiction of her mother, dressed in green, at Andalusia Farm

Anna Gay Leavitt / Georgia College & State University

One of the first paintings O’Connor created after her diagnosis was a self-portrait. She’s wearing a halo-like straw hat and holding a pheasant. Both O’Connor and the bird stare directly at the viewer.

“You know, I think it’s hilarious,” Simon tells GPB. “She’s like, ‘Look at me, American Gothic. I’m sick. I was forced to come back to Milledgeville. But I’m a saint.’ … I think you can read this on so many levels.”

Many of O’Connor’s works from the Andalusia period reflect her rural surroundings, with colorful paintings of fowl, flowers and farmhouses. But she never let her attentive eye stray too far from the people around her, whom she would explore in various media—from satirical cartoons of fellow students to sensitive portraits of a Black woman, likely a farm worker, crocheting.

Rather than detracting from O’Connor’s sharp prose, these artworks “complement and expand” what we know about her creative sensibilities, Munnell tells Artnet’s Min Chen. “You can see the ways that her ideas and the way she described people carried over. Her fiction is often quite dramatic and her characters are often described in these big, bold ways. This carries over in how she painted.”

“Hidden Treasures” is on view at the Andalusia Interpretive Center in Milledgeville, Georgia, through the summer.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

#see #flannery #o039connor039s #littleknown #visualSee Flannery O'Connor's Little-Known Visual Artworks That Had Been Collecting Dust in Storage

See Flannery O’Connor’s Little-Known Visual Artworks That Had Been Collecting Dust in Storage

From childhood cartoons to thoughtful self-portraits, the acclaimed Southern writer was always a keen observer of her surroundings

Many of O'Connor's artworks drew on the rural Southern surroudings of her family farm in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Georgia College & State University

“Any discipline can help your writing: logic, mathematics, theology, and of course and particularly drawing,” Flannery O’Connor wrote in an essay titled “The Nature and Aim of Fiction.” “Anything that helps you to see, anything that makes you look. The writer should never be ashamed of staring. There is nothing that doesn’t require his attention.”

As a writer, O’Connor took her own advice to heart. Across dozens of short stories and two novels published before her early death from lupus at age 39, she “refused to seek success by generating nostalgia for a mythologized past, instead sketching masterful portraits of the people she observed around her, in all their flaws and contradictions,” writes Smithsonian magazine’s Ellen Wexler.

But O’Connor didn’t just sketch people with her words. Long before she attended the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop or the Yaddo writers’ retreat in upstate New York, she drew cartoons and caricatures for her high school and college newspapers. Even as her writing career progressed, she never ceased turning her intense gaze toward visual art, from oil paintings to linoleum-block prints.

In celebration of her 100th birthday on March 25, 2025, Georgia College & State University, O’Connor’s alma mater, gathered 70 rare visual artworks from throughout her life for an exhibition called “Hidden Treasures” at Andalusia, the farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she spent the last 14 years of her life.

A cartoon from O'Connor's college days

Georgia College & State University

“Scholars continue to study Flannery, to research her, and to use her as a model in creative writing programs,” Katie Simon, a literary scholar and the interim executive director of the Flannery O’Connor Institute for the Humanities at GCSU, says in a statement. “She’s taught as an example of literature—but scholars are starting to look at her as a visual artist, as well. These paintings reveal that she never stopped creating visual art until her death.”

Many of the pieces in the exhibition are on public view for the first time. Although scholars and O’Connor fans were aware of her artworks, only “her family knew exactly where they were, which was a storage unit in town—storage unit behind the Cook Out,” a fast-food restaurant chain, as Andalusia curator Cassie Munnell tells Devon Zwald of Georgia Public Broadcasting.

Stashing O’Connor’s paintings, prints and drawings away in an obscure storage unit was no accident, however. The writer’s mother, Regina Cline O’Connor, and early trustees of her estate “weren’t sure if she would be rightly recognized as what she is: one of the greatest short story writers,” Farrell O’Gorman, a new trustee of the O’Connor estate, explains to the New York Times’ Walker Mimms. “I think they were worried that the paintings might somehow distract from her achievements as a writer.”

Born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1925, O’Connor grew up in Milledgeville and graduated from GCSU. While she prepared for a writing career up north, she was forced back to Andalusia in 1950, when she started developing symptoms of lupus.

The autoimmune disease meant that when O’Connor, a devout Catholic, wasn’t going to mass or tending to her peafowl, she spent much of her time on the first floor of the farmhouse—a state of immobility and isolation that honed her creative talents in prose and paint.

O'Connor's depiction of her mother, dressed in green, at Andalusia Farm

Anna Gay Leavitt / Georgia College & State University

One of the first paintings O’Connor created after her diagnosis was a self-portrait. She’s wearing a halo-like straw hat and holding a pheasant. Both O’Connor and the bird stare directly at the viewer.

“You know, I think it’s hilarious,” Simon tells GPB. “She’s like, ‘Look at me, American Gothic. I’m sick. I was forced to come back to Milledgeville. But I’m a saint.’ … I think you can read this on so many levels.”

Many of O’Connor’s works from the Andalusia period reflect her rural surroundings, with colorful paintings of fowl, flowers and farmhouses. But she never let her attentive eye stray too far from the people around her, whom she would explore in various media—from satirical cartoons of fellow students to sensitive portraits of a Black woman, likely a farm worker, crocheting.

Rather than detracting from O’Connor’s sharp prose, these artworks “complement and expand” what we know about her creative sensibilities, Munnell tells Artnet’s Min Chen. “You can see the ways that her ideas and the way she described people carried over. Her fiction is often quite dramatic and her characters are often described in these big, bold ways. This carries over in how she painted.”

“Hidden Treasures” is on view at the Andalusia Interpretive Center in Milledgeville, Georgia, through the summer.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

#see #flannery #o039connor039s #littleknown #visual