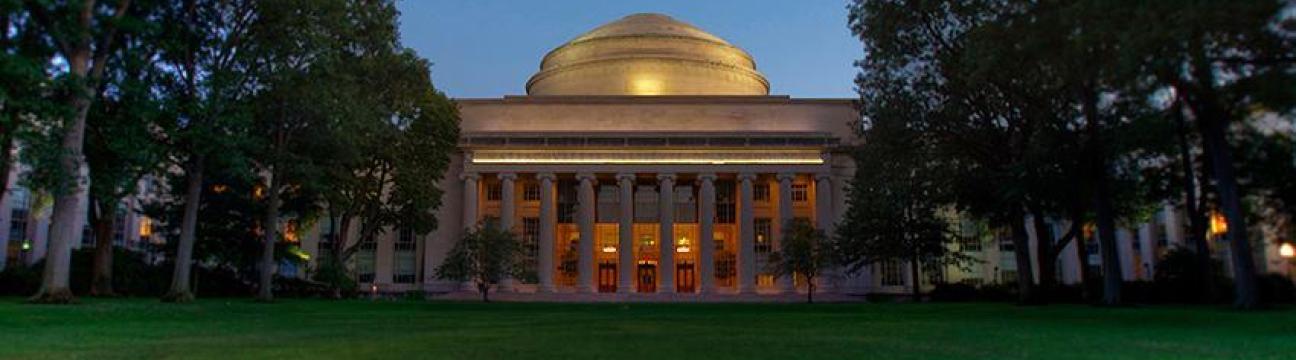

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a world leader in research and education.

192 people like this

0 Posts

0 Photos

0 Videos