The secret of good metaphors

uxdesign.cc

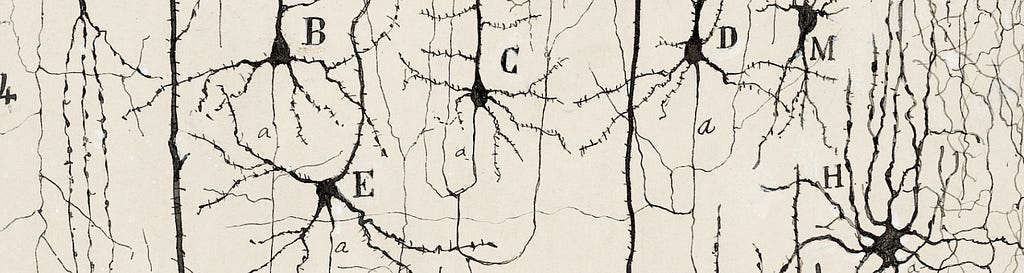

How do metaphors and analogies work, and what makes a good metaphor?Heres something that has always fascinated me: our understanding of the human body, particularly the brain and nervous system, has been profoundly shaped by the tools and technologies of each era. During the rise of mechanical craftsmanship, we began perceiving the body and brain as hydraulic systems (Descartes, 1600s) and intricate clockwork mechanisms of gears and springs (La Mettrie, 1700s). The industrial revolution brought new perspectives: the telegraph system with its information-carrying electrical wires transformed our view of the nervous system (Helmholtz, 1800s), while the steam engine, with its energy and pressure, became a model for understanding the brain (Freud, 1800s). Perhaps the most striking examples emerged in the 20th century with the rise of electronics and networks. The brain was first envisioned as a telephone exchange switchboard connecting signals (Sherrington, 1930s), and later conceptualized as a computer with input, output, processing and storage (Miller, Galanter & Pribram, 1960s). And this pattern continues: we now talk about the brain through comparisons to the internet and AI neural networks.Our bodies and brains are incredibly complex systems. To comprehend them, we naturally turn to what we already understandthe most sophisticated technologies of our timeand we do so through metaphors and analogies. As designers, we dedicate substantial time to crafting the perfect visual metaphors that make the novel and unexpected feel familiar and approachable. But how do metaphors and analogies work? And what makes a good metaphor?Why we love metaphorsAt its core, metaphors perform a simple yet profound function: they bridge the unfamiliar with the familiar. They connect what lies beyond our grasp to what we already know intimately. And what could be more intimate than our direct experience of the world? One of metaphors most powerful aspects is their ability to bring distant concepts within reach of our humanscale.Source: Eureka, Physics of Particles, Matter and theUniverseOur brains, shaped by millions of years of evolution, excel at perceiving and understanding the world at the scale of our bodies. Research has demonstrated that the further we go away from our human scale the less accurate our perception gets. From the microscopic scales of atoms and nano seconds to the macroscopic scales of galaxies and millions of years, everything outside of our human experience seems complex, abstract, ungraspable. In response, we instinctively map these complex and abstract concepts onto embodied experiences. We are able to think about how time passes via our implicit understanding of how we and other objects move through space. We are able to think about degree of familiarity and intimacy in relationships in terms of physical proximity. Metaphors translate abstract ideas into perceptions. They turn what we can think into what we canfeel.Paper, touch andparrotsLets look at a concrete example. How do you make a complex machine accessible to everyone? In computing, the answer has always been: find the right metaphor.In the early days, computers were complex calculators that only specialists could operate, with users submitting punch cards and waiting hours for results. The breakthrough came in 1970 when Xeroxa photocopier companyestablished PARC, a research center dedicated to explore the paperless future, and tasked it with an ambitious mission: making computers accessible to everyone, even children.The team found their answer in a simple metaphor: paper. They noticed how naturally office workers handled documentsmoving them, stacking them, filing them away. This observation became the foundation for the modern computer interface. They created visual representations of familiar items: a desktop surface, folders, a trash can, files you can pick up and move, and overlapping windows that mimicked papers on a desk. Drawing from research on how children learn through physical manipulation, they designed an interface that felt as natural as arranging items on a desk. They recognized the power of metaphors to rewire ourbrain.The paper metaphor creates clear affordances: when you see a folder, you know you can put things in it; when you see a trash can, you know you can throw things away; when you see a window, you know you can move it around. The metaphor didnt explain the computerit made it immediately clear how to use it. And ironically, paper became the primary metaphor for the paperless world.Xerox Alto, the very first computer using the paper metaphor. Screenshot of Smalltalk GUI, copyrighted 1980. Courtesy ofPARC.Today, as Dan Saffer writes: no one addresses his computer without some metaphoric mediation. This is still true in smartphones, where weve developed a new language of interaction: we pull to refresh, swipe to dismiss, pinch to zoom. The evolution of these metaphors mirrors how our relationship with technology has changed. Weve moved from the paper metaphor to a physics inspired interaction model.This shift from professional to physical metaphors parallels computings journey from office tools to personal devices. While desktop computers still use the paper metaphor, smartphones have adopted a language stripped of most cultural or professional context. By embracing simple physical metaphors, smartphones achieved something remarkable: they made computing accessible to a much wider audience. This suggests how universal metaphors, when well chosen, can help make complex systems accessible.Today, we face this challenge with Generative AI and Large Language Modelssome of the most abstract and complex technologies of our time. Confronted with these new tools, we instinctively reach for familiar frameworks: some define LLMs as sophisticated copying machines (stochastic parrots or blurry JPEG of the web), others envision them as crowds, inscrutable gods, aliens, or even food. These metaphors help bring seemingly magical technologies within our grasp, but each offers a different way of understanding them. When we see AI as a copying machine, we focus on its limitations; when we see it as a crowd, we think about emergence; when we frame it as an alien intelligence, we contemplate its otherness. As Sean Trott observes: our choice of framing is exerting a subtle influence on the direction of our thought.What is the right metaphor?To understand computers, smartphones or LLMs we need the right metaphors. As Steven Jay Gould writes: We often think naively that missing data are the primary impediment to intellectual progress, just find the right fact and all the problems will dissipate, but barriers are often deeper and more abstract than thought. We must have access to the right metaphors, not only to the requisite information. Revolutionary thinkers are not, primarily, gatherers of facts but weavers of new intellectual structures. Beyond technical specifications and capabilities, its the metaphors we choose that will determine how we understand and use these technologies.However, some metaphors we assume to be universal are actually deeply cultural. Lets look at time. English speakers conceptualize time spatially with the past behind us and the future ahead. But Aymara speakers from the Andes use a completely different framework based on visibility rather than direction of movement. For them, The past, visible, thus stands in front of the speaker, while the future, unseeable, looms behind. Their gestures match this perspective: they point forward when discussing the past and backward for thefuture.Other cultures use entirely different spatial metaphors. Yupno speakers in New Guinea conceptualize time in relation to the mountains around them: the future flows uphill while the past flows downhill. Perhaps most surprisingly, researchers found that Tupi-Kawahb speakers in Brazil appear to organize time without using spatial metaphors at all, challenging the assumption that time-space mapping is universal.These examples reveal that metaphors we assume to be universal are often deeply cultural. When creating new metaphors, we should question our assumptions about whats intuitive or universal, recognizing that different metaphors might serve different communities better.Finite and infinite metaphorsLets go back to our brain metaphors. In the late 1800s, while many scientists were embracing mechanical and electrical metaphors for the nervous system, the Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramn y Cajal proposed a radically different vision. Having grown up in the Spanish countryside, he saw the brain not as a fixed machine but as a living gardenneurons were trees that could grow and branch, axons were climbing vines, and dendrites were delicate flowers blooming in the cerebral forest. This wasnt just poetic language. Cajal actively rejected the dominant telegraph metaphor of his time, arguing that a rigid network of wires contradicted what he observed: the brains remarkable ability to change and adapt. Its garden metaphor captured something fundamental that mechanical metaphors couldnt: the brains plasticity, its capacity for growth and transformation.Purkinje cell drawn by Cajal from the human cerebellum at the back of the head, which regulates balance for walking and standing. Courtesy of Cajal Institute, Cajal Legacy, Spanish National ResearchCouncilThe brain is neither truly a garden nor a machine (whatever the most advanced machine of our time is). But while the machine metaphor attempts to map a complex unknown (the brain) to a complex known (the machine), the garden metaphor shifts entirely our vision of what a brain is, and I would argue that it also shifts our vision of what a garden is. This gives us another insight into what makes a good metaphor: they dont just map one object to another but rather shift our perspectives on bothobjects.James P. Carse develop this idea in the fascinating Finite and Infinite Games: It is not the role of metaphor to draw our sight to what is there, but to draw our vision toward what is not there and, indeed, cannot be anywhere. Metaphor is horizontal, reminding us that it is ones vision that is limited, and not what one is viewing. This shift in perspective is the reason why some metaphors are so powerful.We need metaphors to expand our thinking, to look at the world in new ways. Much like scientific models, I see metaphors as frameworks through which we perceive and analyze the world. Some metaphors might be models yet to emerge, offering glimpses of new ways to structure our understanding.In conclusion, we often think we use metaphors to explain ideas, but I believe good metaphors dont explain but rather transform how our minds engage with ideas, opening entirely new ways of thinking. When crafting metaphors or communicating complex ideas, our role isnt really to explain what exists, but to cultivate spaces where new understanding canbloom.This text is part of a series reflecting on my practice as a designer working in science communication. You can find my work and get in touch here: https://www.louischarron.io/SourcesFinite and Infinite GamesJames PCarseMetaphors we live byGeorge Lakoff, MarkJohnsenShortcutJohnPollackThe role of metaphor in communication and thoughtPaul H. Thibodeau, Teenie Matlock, Stephen J. Flusberghttps://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/lnc3.12327Of Microscopes and Metaphors: visual analogy as a scientific toolMatteo Farinellahttps://matteofarinella.com/Of-Microscopes-and-MetaphorsA History of the GUIJeremy Reimerhttps://arstechnica.com/features/2005/05/gui/The Father of Modern Neuroscience Discovered the Basic Unit of the Nervous SystemBenjamin Ehrlichhttps://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-father-of-modern-neuroscience-discovered-the-basic-unit-of-the-nervous-system/How much does our language shape our thinking?Manvir Singhhttps://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/12/30/how-much-does-our-language-shape-our-thinkingThe secret of good metaphors was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

0 Reacties

·0 aandelen

·19 Views