WWW.POPSCI.COM

From Tin Cans to AI: How a century of deep-sea filmmaking revolutionized ocean exploration

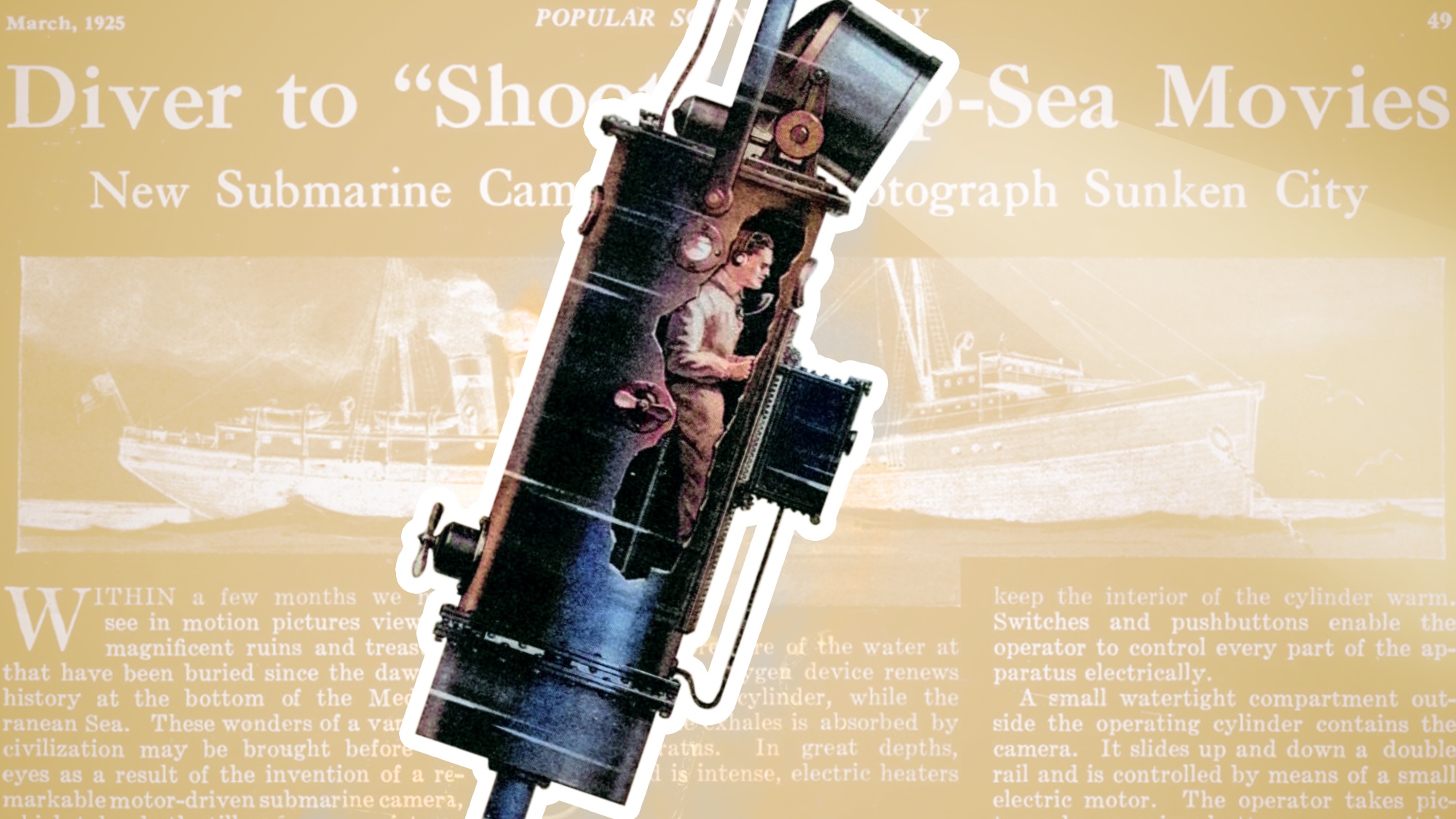

When Hans Hartman, a civil engineer, attempted to film the ocean depths in 1917, he pioneered what would become the first deep-sea ROV, or remotely operated vehicle. During an era of silent movies and wartime U-boats, Hartmans ambitious inventiona 1,500-pound electric, submarine cameracould be lowered to a depth of 1,000 feet to capture images of sunken ships and submerged treasures. Despite featuring a gyroscope for stability, a motorized propeller for controlled rotation, and an innovative light source, as Popular Science explained, it had a serious limitation: The hulking apparatus had to be operated blindly from a ships deck, which meant it was impossible for the cameras operator to see what they were filming until the footage was viewed later.Undeterred, Hartman pushed further. In 1925, Popular Science showcased his next breakthrougha cylindrical apparatus (seen above) attached to a ship by a cable, housing a submersible, motor-driven camera, as well as enough room for a person who could control the camera, or communicate with crew members nearby to aid with various underwater missions, such as salvaging. The vertical, tin-can-like submarine, equipped with porthole windows and a powerful spotlight, allowed the operator to go down into the water with a camera and photograph whatever he chooses. While Hartman initially set his sights on a sunken Roman city in the Mediterranean, his motion-picture-taking craft could reach depths of 2,000 feet to film marine life with unprecedented clarity. A century ago, Hartmans innovations established the foundation for a field that would evolve from cumbersome surface-controlled contraptions to todays sophisticated AI-powered autonomous submersibles.The March 2025 issue of Popular Science featured a story on the lengths moviemakers went to film underwater. Image: Popular Science Hartmans contributions came at a time of rapid transformation in photography, motion pictures, and ocean exploration. Though Thomas Edison had patented his Kinetoscope more than two decades earlier, motion-picture technologiessuch as the 35mm film and cabinet-size cameras used for filmingremained finicky and unreliable, forcing early filmmakers to shoot in controlled studio environments. It would be roughly a decade after Edisons 1891 invention before outdoor scenes became possible, like the famous footage of the Wright Brothers first flight.As motion-picture technology progressed, parallel developments in submarine warfare technology, industrial shipping expansion, and a growing interest in marine archaeology created demand for more effective ways to document the oceans depths.Jacques Cousteau emerged as perhaps the most influential 20th-century figure in deep-sea exploration and underwater filmmaking. In the 1940s, Cousteaus co-invention of the Aqualung (SCUBA) revolutionized diving and underwater exploration. His 1959 Diving Saucernicknamed Denisecould carry a crew of two and dive as deep as 350 meters, remaining submerged for up to five hours. Cousteau and his team captured spellbinding footage that culminated in the landmark documentary series The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau (19681976).Jacques Cousteau pictured in Nice, France in April 1964 explaining how five men will spend the night underwater in this new housing. Image: UPI photo via Getty Images BettmannBuilding on Cousteaus legacy and the public fascination hed created for marine life, shipwrecks, and ancient ruins, filmmakers continued to dive deeper. Haunting images of the Titanic first made headlines in 1985 when Woods Hole Oceanographic Institutions ROV, Argo, equipped with high-resolution cameras and sonar, located the wreck at a staggering depth of 12,500 feet.In the 21st century, whats an otherworldly conquest without billionaires vying to be first? The Titanics ghostly allure has drawn numerous ultra-wealthy, deep-sea enthusiasts to its resting place in privately owned submarines, including the tragic implosion in 2023 of OceanGates Titan submersible. Following the 1997 release of his blockbuster film, Titanic, deep-pocketed filmmaker James Cameron returned to the shipwrecks site numerous times, employing self-designed, innovative ROVs to explore the ships interior. His 2003 documentary Ghosts of the Abyss revealed the wrecks incredibly well-preserved remains.In 2012, Cameron set a record for the deepest solo dive when he used his personal vessel, the Deepsea Challenger, to explore and film the Mariana Trench at nearly 36,000 feet, about seven miles down. Spying the ocean floor through 9-1/2 inches of glass, his expedition produced some of the most detailed footage ever recorded of Earths deepest oceanic trench. With ongoing marine research in the works, Camerons fascination with the deep has yielded a new expedition series, OceanXplorers, whose first season debuted in 2024Cousteau redux?Todays deep-sea filmmaking frontier increasingly belongs to AI-driven, autonomous submersibles. What began in 1917 with Hartmans tethered ROV has evolved into sophisticated AUVs, or autonomous underwater vehicles, like those operated by Schmidt Ocean Institute. From sidling up to underwater volcanoes to exploring hydrothermal vent fields, these underwater robots are the 21st centurys deep-sea filmmakers, conducting unmanned missions to film and collect critical marine data. Such technological leaps have elevated deep-sea documentary filmmaking to extraordinary heightsor depthswith documentaries like BBCs Blue Planet (2001) and Blue Planet II (2017), establishing new standards for underwater cinematography.Researchers and filmmakers now deploy self-operating sail drones with high-resolution cameras and real-time streaming capabilities, enabling continuous monitoring of deep-sea ecosystems that supports both marine conservation and scientific discovery.Among todays chief innovators, marine ecologist and filmmaker David Gruber stands out for his groundbreaking work with biofluorescent imaging, which has revealed how various marine species emit light in ways previously invisible to the human eye. His remarkable footage has been featured in major scientific studies and documentaries.From Hartmans pioneering electric cameras to todays AI-controlled AUVs, deep-sea filmmaking has come a long way in a century. What began as an experimental tool for documenting shipwrecks and uncovering ancient treasures has evolved into a vital means of exploring Earths final frontierthe vast and mysterious ocean that envelops more than 70 percent of its surface, gave birth to life, and gives our planet its distinctive blue hue among the cosmos.

0 Comments

0 Shares