MITs new biofabrication technique for multi-directional artificial muscle tissue and 3D printing an eye

3dprintingindustry.com

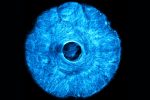

Researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed a new way to grow artificial muscle tissue that contracts in multiple directions, mimicking the movement of natural muscles more closely than ever before.Published in Biomaterials Science, this technique introduces a microtopographical stamping method that precisely controls how muscle fibers form and align. With potential applications in biohybrid robotics, regenerative medicine, and muscle disease research, the findings could help bridge the gap between engineered and biological tissue.At the center of the research is Simple Templating of Actuators via Micro-topographical Patterning (STAMP), a fabrication process designed to shape muscle growth with microscopic precision.Instead of relying on traditional, complex fabrication methods, the team turned to a surprisingly simple approach, using a 3D printed stamp to create structured grooves in a soft hydrogel. These grooves guide muscle cells as they grow, ensuring they align into functional fibers that can contract in multiple orientations.The study was led by Ritu Raman, the Eugene Bell Career Development Professor of Tissue Engineering at MITs Department of Mechanical Engineering. Funding for the study was provided by the U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR), the U.S. Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).MIT engineers grew an artificial, muscle-powered structure that pulls both concentrically and radially, much like how the iris in the human eye acts to dilate and constrict the pupil. Image via MIT.Artificial iris shows controlled muscle contractionsTo put the method to the test, the researchers created an artificial iris, a biohybrid actuator designed to replicate the way a human eyes pupil expands and contracts.The structure featured two distinct muscle fiber arrangements: one forming concentric circles, the other radiating outward. Both worked together to produce controlled contractions in response to light stimulation, demonstrating a level of coordination rarely seen in engineered muscle tissue.Natural muscle fibers dont grow in perfect straight lines. In the body, their orientations vary, allowing for a wide range of movement. Artificial muscle designs, however, have traditionally been limited to pulling in a single direction.That limitation made it difficult to develop biohybrid actuators capable of complex, multi-axis motion. With STAMP, muscle growth can now be directed in more intricate patterns, bringing artificial tissue a step closer to functioning like its biological counterpart.Accessibility was a key factor in developing the stamping process. Using high-resolution 3D printing, the team fabricated stamps with microscopic grooves that matched the dimensions of individual muscle cells.A protein coating on the stamp ensured clean imprinting onto the hydrogel without damaging the material. Once pressed into place, the stamp created a precise blueprint for muscle fibers to follow. The result was a structured tissue network that maintained its function over extended periods.In addition, computational modeling played a crucial role in validating the technique. Simulations predicted that muscle fibers grown with the STAMP method would contract in a coordinated, multi-directional manner, a prediction that was confirmed through experimental testing.The artificial iris performed as expected, demonstrating the ability to control pupil constriction in a way that closely resembled natural function. While the study focused on skeletal muscle, the method isnt limited to one cell type. Researchers believe it could be adapted for neurons, heart muscle cells, and other tissues to create precisely structured bioengineered materials.Looking ahead, the team sees applications beyond medicine. Muscle-based actuators could provide energy-efficient alternatives to rigid mechanical components in soft robotics, particularly in environments where flexibility is crucial. The ability to create multi-degree-of-freedom (multi-DOF) movement could make biohybrid robots more adaptable and dynamic.The researchers developed a new stamping approach. First, they 3D printed a small, handheld stamp (top images) patterned with microscopic grooves, each as small as a single cell. Then they pressed the stamp into a soft hydrogel and seeded the resulting grooves with real muscle cells. The cells grew along these grooves within the hydrogel, forming fibers (bottom image). Image via MIT.3D printing advances in artificial muscleAway from MIT, Researchers at Northwestern University developed a soft, flexible actuator that allowed robots to mimic human muscle movement through expansion and contraction. Led by Professor Samuel Truby, the device was tested in a worm-like soft robot and an artificial bicep, which successfully lifted 500 grams 5,000 times without failure.Made from rubber and thermoplastic polyurethane, the actuator was low-cost and adaptable, addressing safety and flexibility challenges in robotics. Published in Advanced Intelligent Systems, the study demonstrated potential applications in human-centric environments, offering a cheaper alternative to rigid actuators traditionally used in robotic systems.Three years ago, researchers at the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT) developed a robotic hand that used SLA 3D printed artificial muscles to grip objects with human-like efficiency. This hand was powered by GeometRy-based Actuators that Contract and Elongate (GRACEs), made from a pleated resin membrane that stretched and contracted like biological muscles.An 8-gram actuator lifted 8 kilograms, demonstrating its strength and flexibility. The team connected 18 actuators to enable human-like finger and wrist movements, proving that functional artificial muscles could be 3D printed in a single step, simplifying the fabrication of soft robotic systems.What3D printing trendsshould you watch out for in 2025?How is thefuture of 3D printingshaping up?To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, dont forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter, or like our page on Facebook.While youre here, why not subscribe to our Youtube channel? Featuring discussion, debriefs, video shorts, and webinar replays.Featured image shows MIT engineers grew an artificial, muscle-powered structure that pulls both concentrically and radially, much like how the iris in the human eye acts to dilate and constrict the pupil. Image via MIT.Ada ShaikhnagWith a background in journalism, Ada has a keen interest in frontier technology and its application in the wider world. Ada reports on aspects of 3D printing ranging from aerospace and automotive to medical and dental.

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·14 Views