3D-printed skin could make testing cosmetics on animals obsolete

www.popsci.com

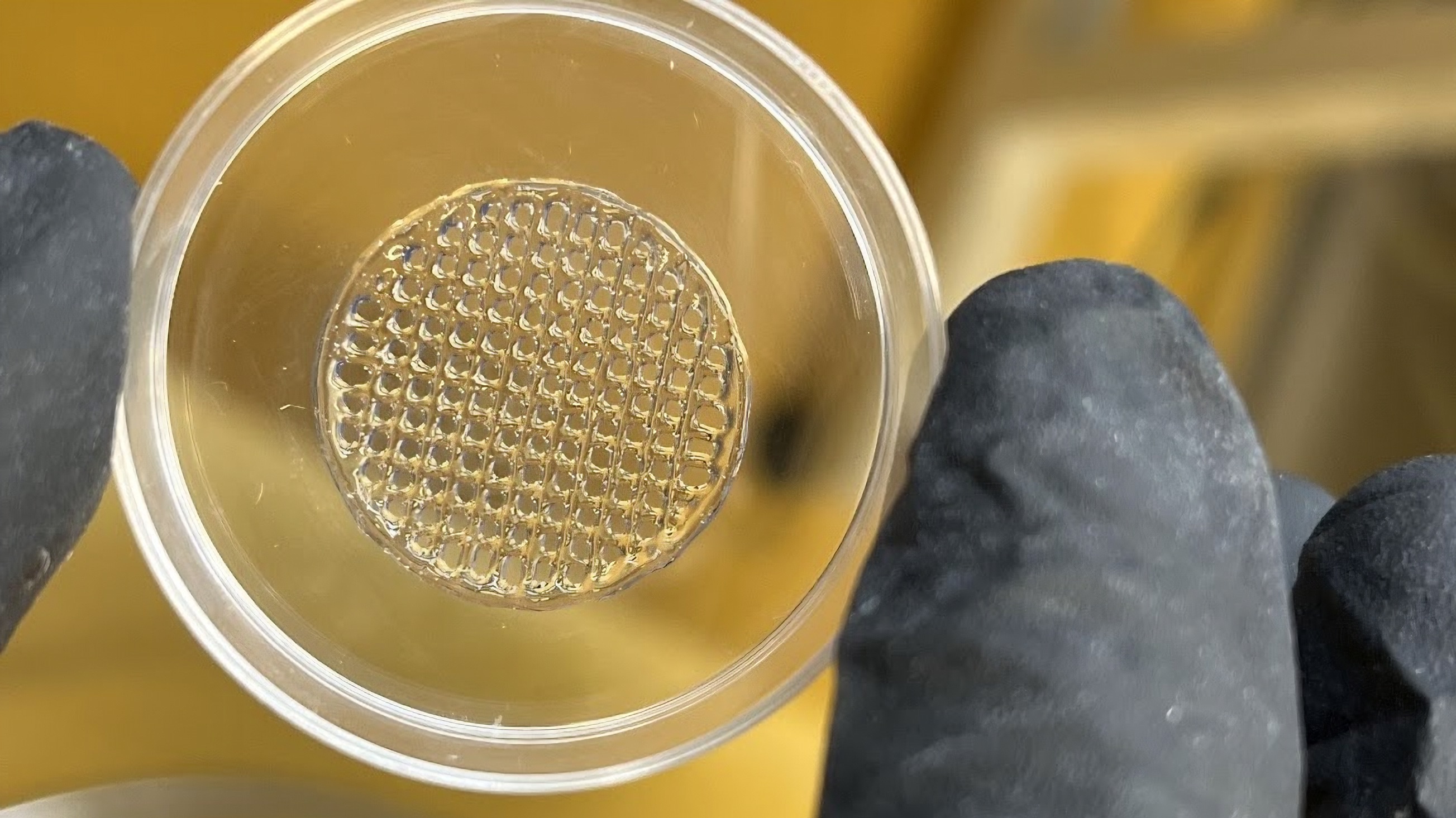

Researchers believe this 3D-printed structure will react to chemicals similarly to human skin.Credit: Manisha Sonthalia, Vellore Institute of Technology Chances are, you or someone you know has used a cosmetic product that was tested on animals. Though once a common practice, it has faced fierce backlash from animal welfare organizations, who argue that animal testing is unnecessarily cruel. At least 44 countries and 12 U.S. states have already passed legislation banning the practice, with some also prohibiting the sale of cosmetics tested on animals. At the same time, testing on animal cells can be particularly useful in determining whether microparticles found in creams, gels, and other common products might seep into human skin and potentially pose health risks.Researchers from Graz University of Technology and the Vellore Institute of Technology (VIT) in India are working on what they believe could be a compromiseoffering the reliability of animal testing without the suffering. Their proposed solution: artificial skin made of 3D-printed hydrogel layers held together by living human cells. Though still in the early stages of development, the researchers believe this bioengineered solution could mimic human skin accurately enough to one day help replace animals in cosmetic testing experiments. In theory, the same approach could also be expanded beyond cosmetics to applications such as drug testing and wound healing.Image: Manisha Sonthalia, Vellore Institute of Technology Building artificial skin with room to growThe researchers initially sought to create a skin imitation that could accurately mimic the three layers in human skin: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. Karin Stana Kleinschek, a researcher at the Institute of Chemistry and Technology of Biobased Systems, said in a statement that they ultimately chose hydrogel as the base for their artificial skin due to its high water content. According to the researchers, this high water concentration creates optimal conditions for integrating living human cells, allowing them to grow and multiply more effectively over a shorter period.A video demonstration of the process shows a 3D-printing machine globing on layers of hydrogel skin substitute onto a square surface. In another image, the hydrogel skin scaffold is arranged in a checkered pattern across a circular platform, resembling a Chex Mix-like design. In theory, these coin-sized constructs should react to cosmetics and other foreign substances in ways similar to human skin.The researchers are currently working toward a goal of keeping their bioengineered material viable for two to three weeks. Once they achieve that milestone, the artificial skin will be considered durable enough for cosmetic testing.All of this could be welcome news for opponents of animal testing. Though precise figures are difficult to pin down, the Humane World for Animalsa group advocating against the practice estimates that around 500,000 animals globally suffer or die each year due to cosmetic testing. Advocates argue that some of the most common procedures, such as applying potentially harmful chemicals directly to animals skin and eyes, are particularly inhumane. In most cases, test animals are euthanized after experiments. But the issue also extends far beyond cosmetics. An estimated 20 million animals die each year in the U.S. alone due to testing related to pharmaceutical drugs and medical research.Researches are 3D-printing everything from kidneys to blood vesselsThe crossroads between 3D-printing and bioengineering is already having an impact on the medical industry and will likely play a much larger role in the coming years. Scientists have experimented with 3D-printed human livers composed of real human cells with the idea that they could one day be used to address a shortage of viable organ donors. Theres signs that vision is well on its way to reality. Last year, a South Korean woman became the first person to benefit from a 3D-printed organ transplant after she received a printed windpipe following surgery to address thyroid cancer. More recently, researchers at Harvard developed 3D-printed blood vessels which they say could make manufacturing a wide range of implantable organs much more viable.

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·21 Views