Ancient funerals may have included a ritual feast on a giant bird

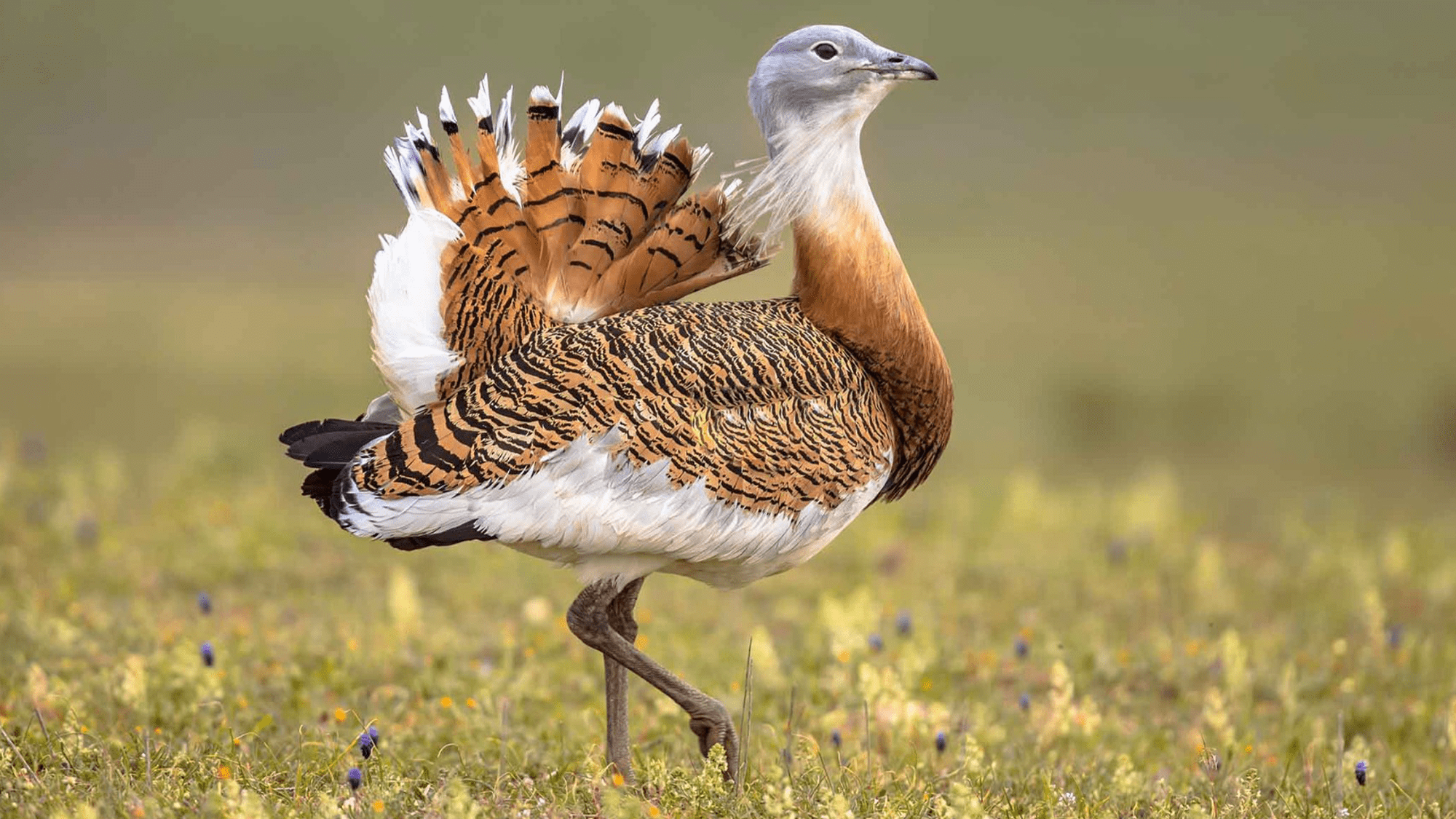

Great bustards are among the largest flying animals in the world. They are widely distributed across much of Eurasia, although their populations are highly fragmented. CREDIT: ©Rudmer Zwerver.

Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

Ancient humans living about 15,000 years ago in present day Morocco may have ritualistically feasted on some of the world’s largest birds as they buried their dead. The butchered bones of great bustards (Otis tarda) that were recently discovered in one of the African continent’s oldest cemeteries hint that these avians were culturally significant at the time. The findings are detailed in a study recently published in the journal IBIS.

Into the Pigeon cave

Roughly 14,700 years ago, a group of people were living and burning their dead in a cave located in what is now Morocco. Called Taforalt cave, or Grotte des Pigeons, this site contains graves of over 30 ancient humans. During this time, mammoths were still grazing the northern steppes and sheep would not be domesticated for another 5,000 years or so.

This group was beginning a transition between a semi-nomadic and a more settled life. Studying the other objects found within their graves offers scientists an insight into their daily lives and culture as a community.

Additionally, the environmental conditions in the cave preserved the bones, tools, and a huge range of biological material. Having access to this kind of DNA evidence allows for researchers to build a more detailed picture of their lives. Earlier work found that they were burning and consuming the medicinal plant Ephedra, along with other foods such as juniper and acorns.

Recent findings suggest their death rituals included the great bustard. Bustards are among the largest flying animals on the planet, with males regularly weighing in at about 44 pounds. Bustards still exist today, but they were once more widespread across Europe, Asia, and parts of north Africa. The new evidence found in this cave confirms that the birds have a long history on the African continent–and have long been valued by humans.

“We see a strong cultural association with the great bustard because the people are not only depositing them in burials, but there’s also evidence that they were eating them as well,” Joanne Cooper, a study co-author and senior curator of the avian anatomical collections at the Natural History Museum in London, said in a statement. “We believe that was part of the funeral rites. It seems to be a feasting set up, which is a very specific type of ritual eating.”

An ancient ritual feast

The bones of butchered and cooked animals have been found in the most high-status graves. Some hold the skulls of wild sheep, but one specific burial has the breastbone, a great bustard with cut marks. The team believes that this is evidence of a meal similar to the turkey eaten on Thanksgiving Day or Christmas now.

The repeated presence of great bustard remains suggests that the avians were culturally significant. It would have taken a great deal of valuable time and effort to catch and prepare the animals, which suggests ritual feasting over routine behavior.

Bones of great bustards found in the graves of the ancient people show cut marks and evidence of butchery. CREDIT: © Natural History Museum.

“This is a communal behaviour that involves special foods that people have to go out of their way for that is then consumed in some kind of special context,” says Cooper. “The habitat for the great bustard isn’t really the kind of the mountainous area around the cave in which the remains are found. They would have had to trek down to the plains to catch the bustards, carry them back up to the cave, prepare them, cook them and eat them. The special context is that they’re associated with these burials.”

Life among the big birds

Great bustards are typically found in open grasslands and farmland, requiring large areas of undisturbed land for breeding and living. Their breeding typically occurs in March, when males will reveal themselves to females. They compete for female attention with elaborate displays and violent fights in an area known as a lek.

They were already naturally vulnerable to human disturbance because they need so much space, but have also been hunted for both food and sport. This hunting and habitat destruction has significantly fragmented their population.

The only population seen in Africa today is in Morocco, where the species is considered critically endangered. This group is closely related to a population in Spain, but also genetically distinct. Still, there has been some debate among biologists about how long great bustards had lived in north Africa. In northwestern Morocco, about 70 birds live in two small areas, but this new evidence indicates that their presence goes back generations.

The team hopes that the discovery showing the ancient human connection to great bustards spurs more conservation efforts to keep this population from going extinct.