Curiosity rover finds key ingredient for past life on Mars

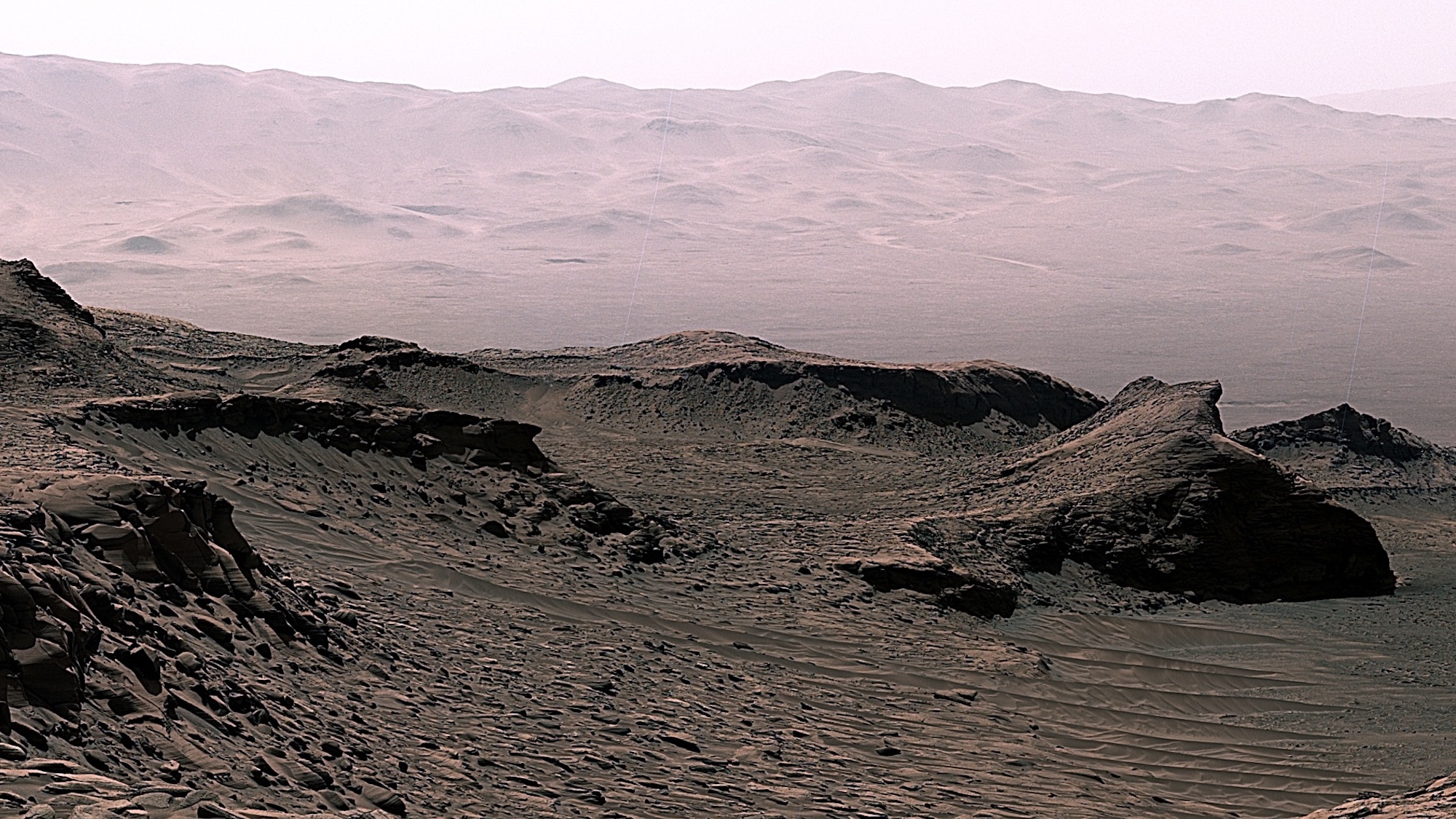

A photomosaic taken by the Curiosity Rover on April 30, 2023 at the Ubajara drill site in Gale Crater, Mars. Rock powder samples drilled here contained substantial amounts of siderite (an iron carbonate mineral). The siderite played a role in ancient carbon cycling processes that impacted conditions at the planet’s surface. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

New samples collected and analyzed by NASA’s Curiosity rover are pushing researchers closer than ever to finding out if Mars was once truly capable of supporting life. According to a paper published on April 18 in Nature, ancient geologic samples indicate the Red Planet at one time featured a carbon cycle—an atmospheric condition that’s necessary for sustaining liquid water on the Martian surface. Taken together with previous evidence pointing to the existence of dried rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans, it’s looking increasingly likely that Earth’s neighbor featured at least some form of life in its distant past.

As with all of Curiosity’s previous work, these latest discoveries come from inside the 96-mile-wide Gale Crater. Located about 4.5 degrees south of the Martian equator, Gale Crater formed following an asteroid or comet strike roughly 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago. At one time, it likely hosted a large, beach-rimmed lake. Curiosity has traveled over 21 miles from its landing site since 2012, and has obtained multiple drill site samples from layers of Martian sediment beneath it. One of the mission’s long term goals has been digging deep enough into the geological layers so that researchers can peer as far back into the planet’s history as possible. Recently, Curiosity achieved just that at three sulfate-rich drill sites located on Gale Crater’s Mount Sharp.

In those drill sites, Curiosity detected deposits containing an iron carbonate material called siderite. According to Ben Tutolo, a University of Calgary associate professor of Earth, Energy, and Environment Studies as well as a NASA Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover team, the data marks a major moment in the search for extraterrestrial life.

“The discovery of large carbon deposits in Gale Crater represents both a surprising and important breakthrough in our understanding of the geologic and atmospheric evolution of Mars,” Tutolo said in a statement. “The abundance of highly soluble salts in these rocks and similar deposits mapped over much of Mars has been used as evidence of the ‘great drying” of Mars during its dramatic shift from a warm and wet early Mars to its current, cold and dry state.”

Previously, experts learned the ancient Martian atmosphere was rich in carbon dioxide (CO2), but lacked enough evidence of sedimentary carbonate materials. These materials would suggest that Mars once included enough carbon dioxide in its atmosphere to support not just ice, but liquid water. This past era on the planet now seems far more likely, thanks to Curiosity’s latest findings. Over time, however, solar wind and radiation likely siphoned away the Martian atmosphere, gradually thinning it to the point where carbon dioxide began transforming into rock.

“The broader implications are [that] the planet was habitable up until this time, but then, as the CO2 that had been warming the planet started to precipitate as siderite, it likely impacted Mars’ ability to stay warm,” Tutolo explained.

Moving forward, the team hopes to further study additional sulfate-rich regions of Mars to reinforce their latest findings. Doing so will also help them gain a better understanding of the planet—and any past residents. In the meantime, exploring these Martian mechanisms can help scientists better understand similar processes here on Earth.

“The most remarkable thing about Earth is that it’s habitable and it has been for at least four billion years. Something happened to Mars that didn’t happen to Earth,” said Tutolo, before offering a word of caution:

“Studying the collapse of Mars’ warm and wet early days also tells us that habitability is a very fragile thing.”