Mysterious Microbial Obelisks Colonize our Gut, Mouth, and Stool

www.discovermagazine.com

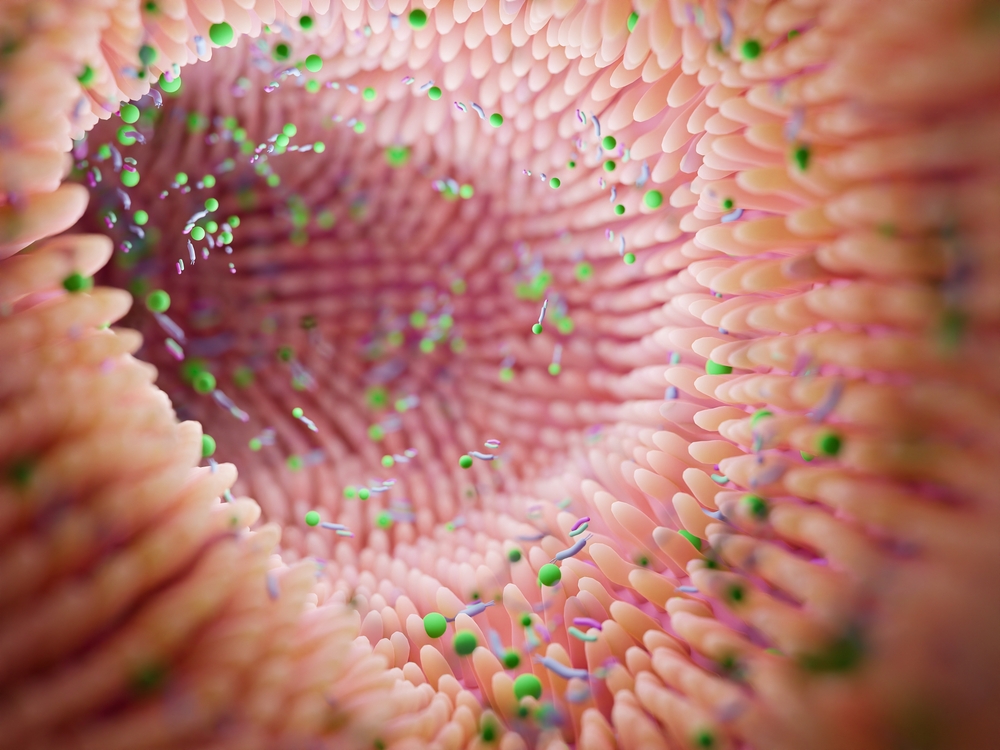

Researchers have discovered mysterious new microbes that colonize the microscopic world inside our mouths and digestive tracts.These obelisks, as they've been named, are minuscule bits of ribonucleic acid (RNA) that serve an unknown function, even though their presence could be widespread in the microbiome, according to a recent study published recently in Cell. Obelisks and ViroidsIts unclear exactly what obelisks are even the researchers who discovered them still know very little. Ivan Zheludev, a biochemist at Stanford University and the first author of the paper, and his colleagues, classify these obelisks as viroid-like RNAs. Viroids themselves are only found in plants, so far.Viroids are a group of noncoding sub viral RNAs that infect plant hosts, wrote the authors of a study published in PLOS Pathogens.They have circular RNA genomes and replicate autonomously without the help of a virus. Originally considered pathogenic, other viroid infections were found to be symptomless or latent.Outside of plants, the only other thing that even slightly resembles these obelisks are delta viruses such as the agents that cause Hepatitis D. In this disease, the microbes are considered a satellite sub virus because they require a helper virus to infect cells. Obelisks are somewhat like these because they are made of RNA.The Gut, Mouth, and StoolIn the recent study, Zheludev and his colleagues examined previously published raw data taken from humans around the world. They found these obelisks in the gut, mouths, and even in human stool, from people on different continents.Many of these obelisks only loosely resembled each other, so there are likely different types of obelisks.The research team examined one type of obelisk that had colonized bacteria found on human tooth enamel: Streptococcus sanguinis. Many, but not all the S. sanguinis bacteria contained RNA that was part of these obelisks.But just because the team found obelisks in S. sanguinis doesnt mean they are found in all bacteria, or that they are only found in bacteria.Indeed, there may be numerous biological niches (bacterial or otherwise) that could harbor obelisks, says Zheludev.What Does This do to the Human Body?Since researchers know so little about obelisks, its difficult to say whether they play any role in disease, or even beneficial roles in our microbiomes. In the case of the obelisks that colonize bacteria found on our tooth enamel, it may even be protective, though the researchers cant say for certain.Dedicated and detailed study will be needed to examine if any correlations between obelisks and human attributes can be identified, says Zheludev.In the paper, Zheludev and his colleagues still pose several open questions with regards to human health or fitness: How do obelisks affect their host, and are they largely a deleterious or beneficial element to harbor? And what impact, if any, does harboring an obelisk have on meta-host physiology, and is obelisk positivity predictive of human health states?More to ResearchEssentially, researchers have only just discovered that obelisks exist. What ecological function they play, the extent of where they are found, and even how they get around is largely unknown. As far as the latter question is concerned, its possible that they self-replicate, or that like the subviral satellite that causes Hepatitis D, obelisks may need a helper virus to get around.Zheludev notes that the researchers dont know how these things are related to each other, because they dont seem to fit into typical biological categories. Despite inferring phylogenetic estimations for the large obelisk family, we do not confidently know how obelisks are interrelated, he says. This is in part due to how obelisk genome topology violates the site independence assumption of typical phylogenetic tools.One thing that is clear is learning more about these obelisks could reveal more about the building blocks of life itself.Article SourcesOur writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:Joshua Rapp Learn is an award-winning D.C.-based science writer. An expat Albertan, he contributes to a number of science publications like National Geographic, The New York Times, The Guardian, New Scientist, Hakai, and others.

0 Reacties

·0 aandelen

·60 Views