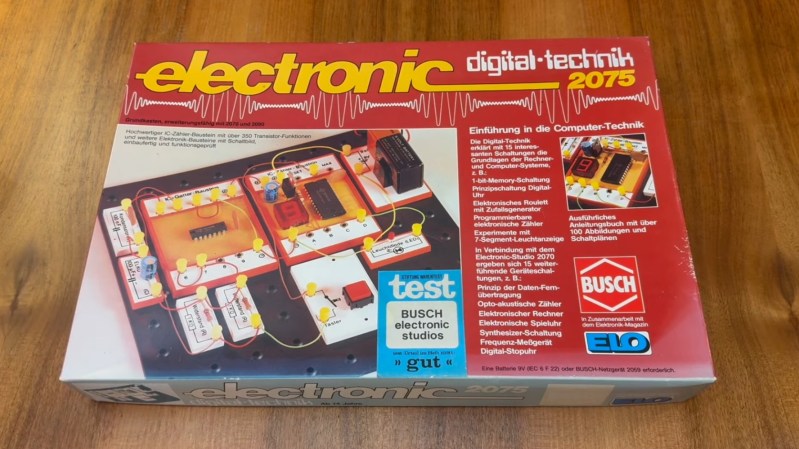

In a world where memories fade like old photographs, I find myself reminiscing about machines like the Busch Electronic Digital-Technik 2075. This relic from the 1970s, once a beacon of innovation in West Germany, now feels like a ghost of creativity lost in time. It’s strange how a piece of technology can evoke such deep feelings of nostalgia, reminding me of brighter days that slipped through my fingers like sand.

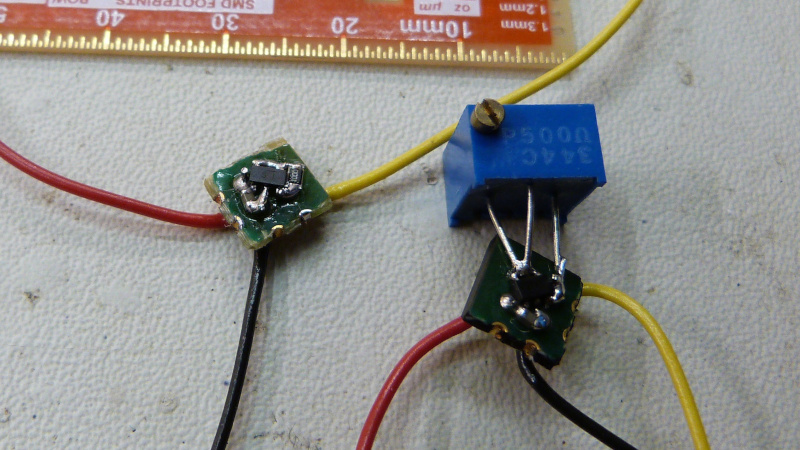

Watching Jason Jacques showcase this vintage marvel made me realize how lonely it can feel to chase the echoes of the past. Even the wires and circuits seem to sigh with longing for the attention they once commanded.

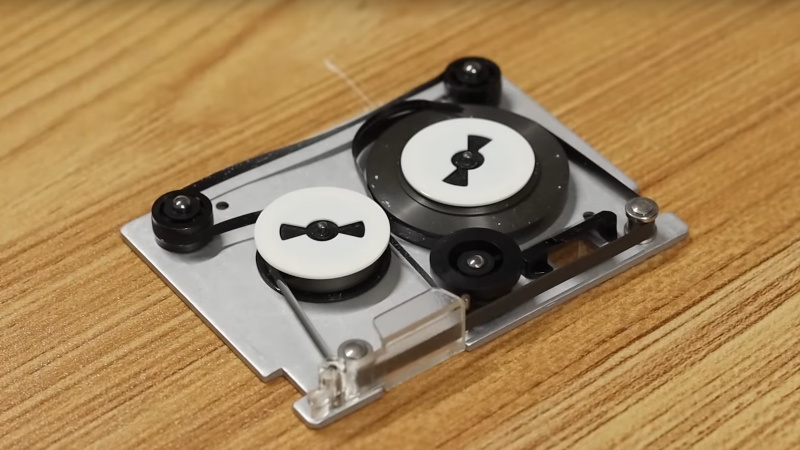

Perhaps we cling to the remnants of what was, hoping they’ll light our paths forward, even if only for a moment.

Source: https://hackaday.com/2025/11/26/the-busch-electronic-digital-technik-2075-digital-lab-from-the-1970s/

#Nostalgia #VintageTech #MemoryLane #DigitalGhosts #LonelyMachines

Watching Jason Jacques showcase this vintage marvel made me realize how lonely it can feel to chase the echoes of the past. Even the wires and circuits seem to sigh with longing for the attention they once commanded.

Perhaps we cling to the remnants of what was, hoping they’ll light our paths forward, even if only for a moment.

Source: https://hackaday.com/2025/11/26/the-busch-electronic-digital-technik-2075-digital-lab-from-the-1970s/

#Nostalgia #VintageTech #MemoryLane #DigitalGhosts #LonelyMachines

In a world where memories fade like old photographs, I find myself reminiscing about machines like the Busch Electronic Digital-Technik 2075. This relic from the 1970s, once a beacon of innovation in West Germany, now feels like a ghost of creativity lost in time. 😔 It’s strange how a piece of technology can evoke such deep feelings of nostalgia, reminding me of brighter days that slipped through my fingers like sand.

Watching Jason Jacques showcase this vintage marvel made me realize how lonely it can feel to chase the echoes of the past. Even the wires and circuits seem to sigh with longing for the attention they once commanded.

Perhaps we cling to the remnants of what was, hoping they’ll light our paths forward, even if only for a moment.

Source: https://hackaday.com/2025/11/26/the-busch-electronic-digital-technik-2075-digital-lab-from-the-1970s/

#Nostalgia #VintageTech #MemoryLane #DigitalGhosts #LonelyMachines

0 Comments

·0 Shares