arstechnica.com

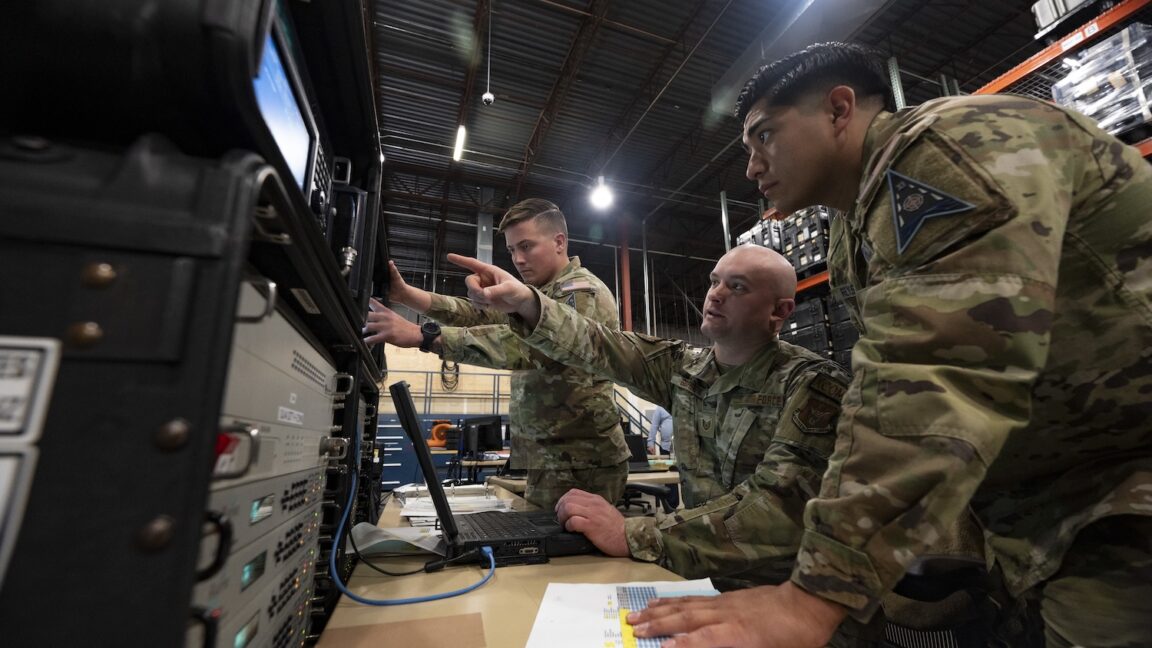

A cutting critique The ax has become an important part of the Space Forces arsenal "Ive terminated 11 major contracts in less than three years." Stephen Clark Mar 20, 2025 8:02 pm | 5 Space Force and Air Force crewmen manage the 25th Space Range Squadrons closed loop range environment during a test of the Remote Modular Terminal (RMT) in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on April 4, 2024. RMT is one a handful of unclassified programs managed by the Space Rapid Capabilities Office. Credit: US Air Force/Capt. Charles Rivezzo Space Force and Air Force crewmen manage the 25th Space Range Squadrons closed loop range environment during a test of the Remote Modular Terminal (RMT) in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on April 4, 2024. RMT is one a handful of unclassified programs managed by the Space Rapid Capabilities Office. Credit: US Air Force/Capt. Charles Rivezzo Story textSizeSmallStandardLargeWidth *StandardWideLinksStandardOrange* Subscribers only Learn moreALBUQUERQUE, New MexicoFor decades, America's big defense contractors have known they can count on a steady flow of business from the Pentagon. You win some, and you lose some. But don't fret. Inevitably, there's a new opportunity to get money from the world's largest military.This paradigm is shifting with the launch of a wave of startups eager to deliver software, missiles, drones, satellites, and other services. It's no surprise that the US military is often the core market for these companies.Since its establishment more than five years ago, the Space Force inherited many of the old ways of doing business ensconced at the Pentagon since World War II. Over the last half-century, numerous defense contractors merged and acquired one another, often escaping scrutiny by promising efficiencies that will result in savings for US taxpayers. Those efficiencies rarely materialized.A fresh set of eyesThe newest military service wants to chart a new path in how the Pentagon buys weapons and services. Over the last decade, military officials have chartered organizations nationwide to seek new technologies that could give US forces the edge over potential adversaries like China and Russia. These include outfits like the Defense Innovation Unit, the Space Development Agency, and an organization named Space Safari.One of these new enterprises is called the Space Rapid Capabilities Office (Space RCO). Headquartered at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the office is "charged with rapidly delivering first-of-their-kind operational space capabilities that protect space assets and defend joint forces from space-enabled attack," according to a Space Force fact sheet. "The office is organizationally optimized to deliver space systems on operationally relevant timelines, with the right authorities, structure, and talent required to do so."Kelly Hammett, director of Space RCO, summed it up this way: "We're supposed to deliver the 'first of' capabilities that are operationally useful on an accelerated timeline. That's been very difficult to do. Space acquisition is a hard business for physics reasons, but also for security reasons, for tech-based reasons, supply chain reasons, all kinds of things."My experience in the last three years as a director of Space RCO is, both internal to our portfolio and across the greater space enterprise, we've done a pretty miserable job of delivering, on shorter timelines, the capabilities that we want," he said. Kelly Hammett, director of Space RCO since 2022. Credit: US Air Force Earlier this month, Ars attended a Space RCO "pitch day" in Albuquerque. where government officials listened to briefings from 10 companies on how they propose helping future military satellites detect threats against them and potentially escape danger during a war that could extend to or start in space. Space RCO used the event to learn what cutting-edge technologies private space companies are already working on. The companies involved were Active Vigilance, Turion Space, Digantara, Anduril, Geost, Impulse Space, Raptor Dynamix, True Anomaly, TRL11, and BlackVe.Officials told Ars this was the first time a journalist has attended one of these Space RCO events. We'll have another report Friday detailing why the Space Force thinks it needs these capabilities and what the companies proposed. It was an enlightening affair because the government has long kept much of what the Space Force and Space RCO do under wraps."Most of what we do is highly classified," Hammett said. "We are getting to the point where we are now delivering systems and capabilities, and my ability to talk about some of those things is being restricted a little bit more due to operational security considerations."So, don't expect an answer to what Satellite X is doing in space right now. However, as Ars has previously reported, the Space Force is getting more comfortable talking about plans for protecting its satellites in orbit, and potentially attacking other spacecraft owned by adversaries. Space assets are already part of the military's surveillance network, providing early warning, navigation, and secure communications to US and allied forces since the dawn of the Space Age. These are all robotic platforms. The Space Force doesn't have its own cadre of astronauts.Out in the openWhat's new is it's now more fashionable to discuss the prospect of space warfare in public, a rhetorical shift that seemed to take off last year. That doesn't mean the Space Force is ready to give up the goods. Space RCO's budget is classified, and it has disclosed only a handful of its programs, such as a new cloud-based architecture to command and control of military satellites, and an effort to develop portable ground terminals with commercial technology to jam enemy satellite signals.Space RCO is modeled on the Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office, whose programs include the X-37B spaceplane and the B-21 Raider strategic bomber. Anduril Industries, founded in 2017, will soon add space missions to its existing portfolio of missiles and drones. Credit: Stephen Clark/Ars Technica "A lot of what I do is not disclosable in the public until we make a shift, which the department is in process of," Hammett said. "We'll take the lead from this administration. ... We're, as a department and as a service, working through how can we talk about more of this stuff more publicly. But we don't have all that guidance in effect. So that can hamstring some of the conversations."The Space Force's greater openness and an appetite for cost-cutting are combining to imperil the grip of the nation's major defense contractors. If programs aren't as secret, space companies don't need the highest security clearances to bid on contracts. And many of these startups are backed by wealthy founders or venture capital.The question Hammett asks today is: Why should the government pay for something billionaires are already funding?While SpaceX led the way in revolutionizing the commercial launch business, a new wave of companies is vying to supply the military with missiles, interceptors, surveillance data, and, as Ars learned at the recent Space RCO pitch day, sensors, propulsion, and space-based AI to shield satellites from attack.Unafraid of the bladeThe 10 companies that participated in the recent pitch day are relative newcomers to the space industry. All but one are under eight years old, and most have fewer than 200 employees.In preparation for the event, Hammett said his office culled a list of 62 interested companies down to 10. The initial list included small firms and traditional military contractors, often called "defense primes" in the arcane world of government acquisition. While Hammett didn't name those companies, chances are you've heard of them. For reference, the Pentagon's five largest contractors are Lockheed Martin, RTX (formerly Raytheon), Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, and Boeing."All those traditional primes opted out of this event, every single one," Hammett said. "We're cultivating an A-team who's willing to work with us, who's hungry, who wants to bring affordability and speed, and it's not the existing industry base."Hammett's office didn't set out to banish the big defense contractors. Simply put, he said they haven't performed or aren't interested in going in the direction Space RCO wants to go.Ive terminated 11 major contracts in less than three years," Hammett said. "Eighty-five percent of those were with traditional defense primes." Most of these programs are classified, so it doesn't become news when a contract is canceled."We try to fix the programs," Hammett said. "We work with the performers, but if they can't get right, and if we have program baselines where they're now exceeding it by 100 percent in cost or schedule ... we're going to fire them and start again."At the same time, venture-backed companies seem to emerge every day from the ether of Silicon Valley or one of the nation's other tech corridors."There's a lot of opportunity to bring other performers into the portfolio, but there are lots of barriers," Hammett said. One of those barriers is leadership at many startups don't have a security clearance. Many small companies don't use the certified accounting systems the government usually requires for federal contracts."You have to be willing to modify your approach, your acquisition strategies, those types of things, so I have directed my team to open the aperture, to find the A-team, wherever the A-team lives, because it doesn't seem to be in our current portfolio," Hammett said. The Space Force has launched three generations of GPS satellites capable of broadcasting a jam-resistant military-grade navigation signal, but ground system delays have kept US forces from fully adopting it. This image shows a GPS III satellite at Lockheed Martin. Credit: Lockheed Martin There's still a place for the Pentagon's incumbent contractors, according to Hammett. Small companies like the ones at Space RCO's pitch lack the national, or even global, footprint to execute the military's most expensive programs."We're trying to build the first of something new, different, at a price point that we can accept," Hammett said. "That's what these types of companies are trying to do. And we're not having to pay the lions share of the cost for that because VC [venture capital] firms and others are kick-starting them."Executives at Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and other traditional defense companies have become warier of bidding on government programs, especially fixed-price contracts where financial risk is transferred from the government to the contractor.The CEO of L3Harris, another established defense contractor, said in 2023 that his company has also declined to bid on fixed-price development contracts. L3Harris leads development of a software system called ATLAS to manage data from a network of sensors tracking rocket launches and objects in orbit. The program is over budget and was supposed to be ready for action in 2022, but it still isn't operational.RTX is in charge of another troubled military space program. The Next-Generation Operational Control System, known as OCX, is designed to allow military forces, including airplanes, ships, and ground vehicles, to access a jam-resistant GPS signal that satellites have been beaming from space since 2005. Twenty years later, the military's weapons systems still haven't widely adopted this M-code signal because of OCX delays."Our traditional defense primes are not doing well," Hammett said. "These programs have sucked for about 12 or 15 years, and they just keep getting more money and more time. We cant do that. The leadership is finally taking action."Running leanThe Defense Department formed Space RCO in 2018 to replace an office called Operationally Responsive Space (ORS), which launched a handful of relatively low-cost missions to demonstrate how launch, reconnaissance, and communications tech could be responsive to real-time tactical military needs. In many ways, ORS was ahead of its time. Its missions focused on supporting US forces on the ground, in the air, or at sea. Now, the military applies many of the tenets ORS started pursuing nearly 20 years ago, with an eye toward applying them to combat in space.Space RCO is a lean operation, with around 50 civilian officials, 20 uniformed military employees, and roughly 200 contractors under Hammett's command. He said the Trump administration's efforts to cut the federal workforce could have a disproportionate impact on small organizations like Space RCO. Hammett said his office hasn't yet lost any probationary employeesas many federal agencies havebut a handful of Space RCO employees took the Trump administration's offer for deferred resignation. These workers were among the 21,000 civilians at the Defense Department who volunteered for the program. Pentagon officials seek to slash 5 to 8 percent of the department's overall civilian workforce."Most of my government workforce are federal civilians, and its having an effect," Hammett said. "Im losing people, and I cannot hire people back because were under a hiring freeze."The Space Force's annual budget last year was approximately $29 billion, about 3.5 percent of the Pentagon's overall budget. Frank Kendall, secretary of the Air Force under President Biden, said last year that the Space Force's budget is "going to need to double or triple over time" to fund everything the military needs to do in space.The Trump administration has not released its budget request for fiscal year 2026, but Washington is bracing for cuts. The Pentagon's enormous budget is not likely to be spared. "Our job is to take the resources we get and build the best Space Force we can," said Gen. Chance Saltzman, the top general in the Space Force.Although most of the details are classified, Hammett contends that Space RCO punches above its weight."I have ...billion-dollar programs that are run by seven people," Hammett said. "If you go you go to the rest of the DOD, you'll have a program office of 500 people to run one of those programs. Were very lean, and we are therefore inordinately impacted when we lose one, two, or three people, and we cant backfill."Stephen ClarkSpace ReporterStephen ClarkSpace Reporter Stephen Clark is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the worlds space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet. 5 Comments