This mantis shrimp-inspired robotic arm can crack an egg

arstechnica.com

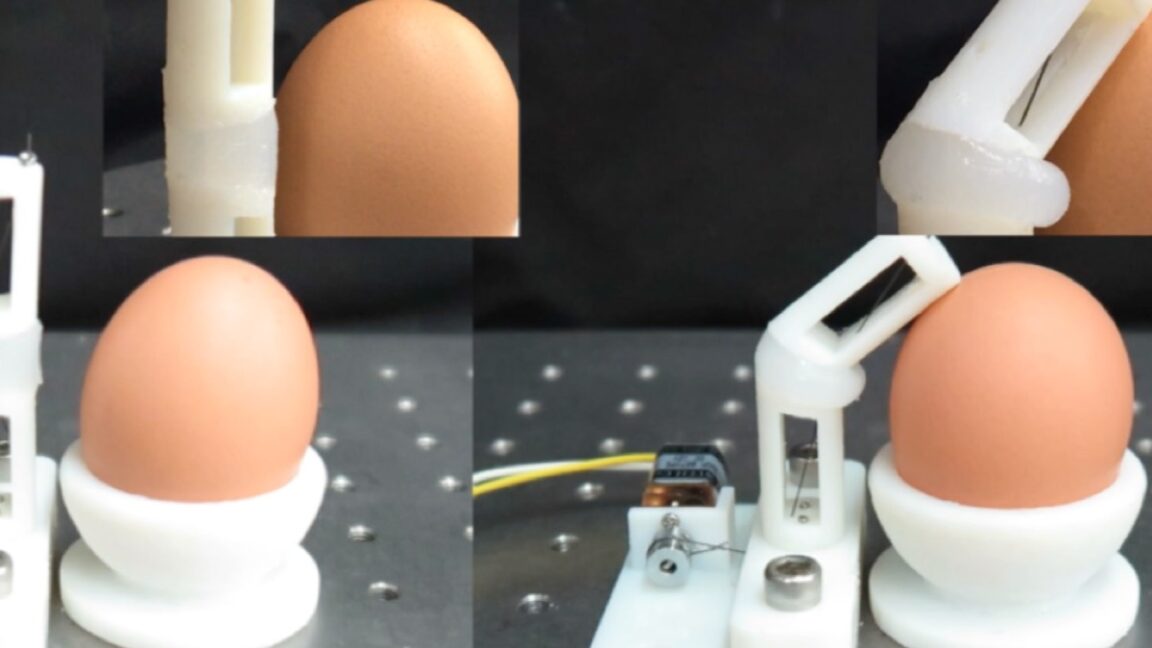

packing a punch This mantis shrimp-inspired robotic arm can crack an egg Device can grab like a hand, crawl across the floor, or jump high, just by pulling on a simple muscle. Jennifer Ouellette Jan 29, 2025 2:00 pm | 4 Credit: Seoul National University Credit: Seoul National University Story textSizeSmallStandardLargeWidth *StandardWideLinksStandardOrange* Subscribers only Learn more An egg-cracking beam relies on a hyperelastic torque reversal mechanism similar to that used by mantis shrimp and jumping fleas. Credit: Seoul National University. We usually think of robots as being made out of hard, rigid materials, but soft robotics seeks to build robotic devices out of more flexible materials that mimic the properties of those found in living animals. Case in point: Korean engineers have built soft robots capable of rapid and powerful joint movements by employing the same mechanism that gives the mantis shrimp such a powerful punch, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Robotics.As we've reported previously,mantis shrimp come in many different varieties; there are some 450 known species. But they can generally be grouped into two types: those that stab their prey with spear-like appendages ("spearers") and those that smash their prey ("smashers") with large, rounded, and hammer-like claws ("raptorial appendages"). Those strikes are so fast (as much as 23 meters per second, or 51 mph) and powerful, they often produce cavitation bubbles in the water, creating a shock wave that can serve as a follow-up strike, stunning and sometimes killing the prey. Sometimes a strike can even produce sonoluminescence, whereby the cavitation bubbles produce a brief flash of light as they collapse.According toa 2018 study, the secret to that powerful punch seems to arise not from bulky muscles but from the spring-loaded anatomical structure of the shrimp's arms, akin to a bow and arrow or a mousetrap. The shrimp's muscles pull on a saddle-shaped structure in the arm, causing it to bend and store potential energy, which is released with the swinging of the club-like claw. It's essentially a latch-like mechanism (technically, Latch-mediated spring actuation, or LaMSA), with small structures in the muscle tendons called sclerites serving as the latch.This isn't the first time scientists have looked to the mantis shrimp as an inspiration for robotics. In 2021, we reported on a Harvard researcher who developed a biomechanical model for the mantis shrimp's mighty appendage and built a tiny robot to mimic that movement. What's unusual in the mantis shrimp is that there is a one-millisecond delay between when the unlatching and the snapping action occurs.The Harvard team identified four distinct striking phases and confirmed it's the geometry of the mechanism that produces the rapid acceleration after the initial unlatching by the sclerites. The short delay may help reduce wear and tear of the latching mechanisms over repeated use.New types of motion The operating principle of the Hyperelastic Torque Reversal Mechanism (HeTRM) involves compressing an elastomeric joint until it reaches a critical point, where stored energy is instantaneously released. Credit: Science Robotics, 2025 Co-author Kyu-Jin Cho of Seoul National University became interested in soft robotics as a graduate student, when he participated in the RoboSoft Grand Challenge. Part of his research involved testing the strength of so-called "soft robotic manipulators," a type often used in assembly lines for welding or painting, for example. He noticed some unintended deformations in the shape under applied force and realized that the underlying mechanism was similar to how the mantis shrimp punches or how fleas manage to jump so high and far relative to their size.In fact, Cho's team previously built a flea-inspired catapult mechanism for miniature jumping robots, using the Hyperelastic Torque Reversal Mechanism (HeTRM) his lab developed. Exploiting torque reversal usually involves incorporating complicated mechanical components. However, "I realized that applying [these] principles to soft robotics could enable the creation of new types of motion without complex mechanisms," Cho said.Now he's built on that work to incorporate the HeTRM into a soft robotic arm that relies upon material properties rather than structural design. It's basically a soft beam with alternating hyperelastic and rigid segments.Our robot is made of soft, stretchy materials, kind of like rubber," said Cho. "Inside, it has a special part that stores energy and releases it all at onceBAM!to make the robot move super fast. It works a bit like how a bent tree branch snaps back quickly or how a flea jumps really far. This robot can grab things like a hand, crawl across the floor, or even jump high, and it all happens just by pulling on a simple muscle. Using HeTRM, energy can be stored in a flexible joint and then released instantly, allowing it to wrap around objects, much like an octopus. Credit: Science Robotics, 2025 Making the soft robotic arm involved a combination of 3D printing and silicone molding, per the authors. The mold had a top and bottom part, with rigid segments fixed within the bottom mold; the top mold had corresponding holes to the cavities for the soft segments. The researchers used laser cutting to make acrylic sheet "slit molds" inserted between the rigid segments. They then poured silicone into the bottom mold, placed the top mold over it, and poured more silicone through the top mold's holes to create the soft segments.The molds and plate were removed after three hours of curing, and the team applied silicon adhesive to bond the rigid segments to the soft joints. They used a titanium wire as an actuating tendon, using Teflon grease to reduce friction. They also used 3D-printed markers along the rigid segments for image tracking.Cho et al. next tested the capabilities of their robotic arm by mounting it onto a platform, using a motor to pull the tendon and a three-pulley measurement system to measure the tendon force. When the motor pulled the tendon in one direction, the beam compressed. Tension was gradually increased until the beam snapped in the opposite direction, eventually returning to its original position.The team demonstrated the robotic arm both gently stroking an egg (without the HeTRM) and cracking the shell (with the HeTRM). The researchers built a two-legged robot that could crawl like a turtle and use the HeTRM and twining octopus-like tentacles comprised of six HeTRM joints arranged in pairs to propel itself across uneven wet sand. They also devised a soft gripper capable of grabbing a falling ping-pong ball or a tangerine or holding delicate objects like a piece of jelly or an origami box without crushing them.Science Robotics, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.ado7696 (About DOIs).Jennifer OuelletteSenior WriterJennifer OuelletteSenior Writer Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban. 4 Comments

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·123 Views