Mars polar ice cap is slowly pushing its north pole inward

arstechnica.com

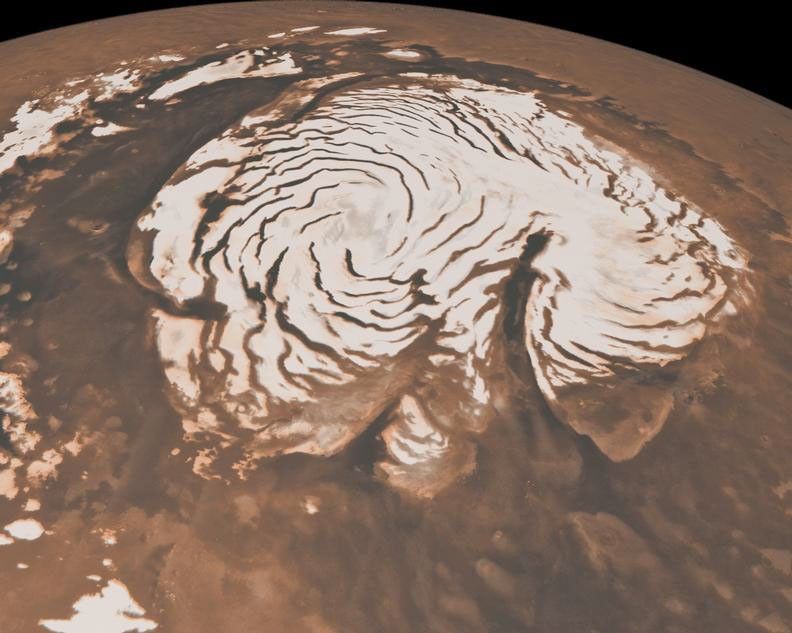

Sinking slowly Mars polar ice cap is slowly pushing its north pole inward That, plus data from the InSight lander, gives us a new view into Mars' interior. John Timmer Feb 28, 2025 4:47 pm | 2 Mars polar ice cap. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS Mars polar ice cap. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS Story textSizeSmallStandardLargeWidth *StandardWideLinksStandardOrange* Subscribers only Learn moreThe north pole of Mars is slowly sinking under the weight of an ice cap that only formed within the past few million years. And, in the process, it's telling us something about what the planet's interior must be like, thanks in no small part to data obtained by hardware we landed in Mars' equatorial regions.That's the conclusion of a new modeling study that produces results that are broadly consistent with earlier work, although quite a bit more detailed. In the process, the work shows how it's possible to take data from radically different data sources and pull them together into a coherent picture.Weighted downWhile the crust of a planet is relatively solid, it bends and breaks in various ways under the strain of plate tectonics. It also flexes in response to ice. The long glacial period that preceded our current interglacial saw sheets of ice that pressed the crust down into the mantle under their difficult-to-conceive weight. With the ice gone, the crust is slowly rising again, in a process called glacial isostatic rebound.Given that Mars is significantly colder and further from the Sun, it's easy to imagine that its polar ice caps have been there for ages, and the planet is frozen and static. But that isn't likely to be the case. Working backward using orbital mechanics, it appears that the poles got more sunlight in the past; plugging that information into Martian climate models suggests the polar ice caps are probably less than 10 million years old.So, the polar ice caps may be new enough that the crust at the poles is still sinking. And, if that's the case, it can tell us something about the crust and the mantle underneath it.But it's not sinking fast enough for us to detect it from orbit. So, instead, researchers built a set of models of the evolution of Mars. These used different assumptions about the properties of Mars' interior, including the amount of heat in the crust, its thickness, etc. Given that there was a range of reasonable values for each of these properties, this resulted in 84 different models. So, the team had to figure out which of those 84 were likely to represent realistic conditions.To figure out which models might be valid, the researchers looked for constraints from other data that could rule some of these models out.Process of eliminationOne of the big constraints comes from NASA's InSight lander, which brought the first seismograph to Mars. If a marsquake that was higher than a 3.8 magnitude were to take place at the north pole, InSight should have picked it up at its equatorial location. Given that it hadn't seen any marsquakes of this sort, then that set a limit on how quickly the crust there is deforming.In addition, radar imaging from in orbit has created images of Mars' polar ice caps that extend down to the crust itself. This can provide information on how badly the shape of the area differs from what you might expect from a spherical surface.The orbiters that carried the radar hardware, along with one or two others, have been orbiting long enough that any major changes in Mars' gravity caused by ice accumulation or crustal displacement would have shown up in their orbital behavior. The orbital changes they do see, "indicates that the increase in the gravitational potential associated with long-term ice accumulation is higher than the decrease in gravitational potential from downward deflection." They calculate that the deformation has to be less than 0.13 millimeters per year to be consistent with the gravitational signal.Finally, the model had to have realistic conditions at the polar ice cap, with a density consistent with a mixture of ice and dust.Out of those 84 models, only three were consistent with all of these constraints. All three had a very viscous Martian interior, consistent with a relatively cold interior. That's not a surprise, given what we've already inferred about Mars' history. But it also suggests that most of the radioactive elements that provide heat to the red planet are in the crust, rather than deeper in the interior. That's something we might have been able to check, had InSight's temperature measurement experiment deployed correctly. But as it is, we'll have to wait until some unidentified future mission to get a picture of Mars' heat dynamics.In any case, the models also suggest that Mars' polar ice cap is less than 10 million years old, consistent with the orbitally driven climate models.In a lot of ways, the new information is an update of earlier attempts to model the Martian interior, given a few more years of orbital data and the information gained from the InSight lander, which also determined the thickness of Mars' crust and size of its core. But it's also a good way of understanding how scientists can take bits and pieces of information from seemingly unrelated sources and build them into a coherent picture.Nature, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08565-9 (About DOIs).John TimmerSenior Science EditorJohn TimmerSenior Science Editor John is Ars Technica's science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots. 2 Comments

0 Comentários

·0 Compartilhamentos

·57 Visualizações