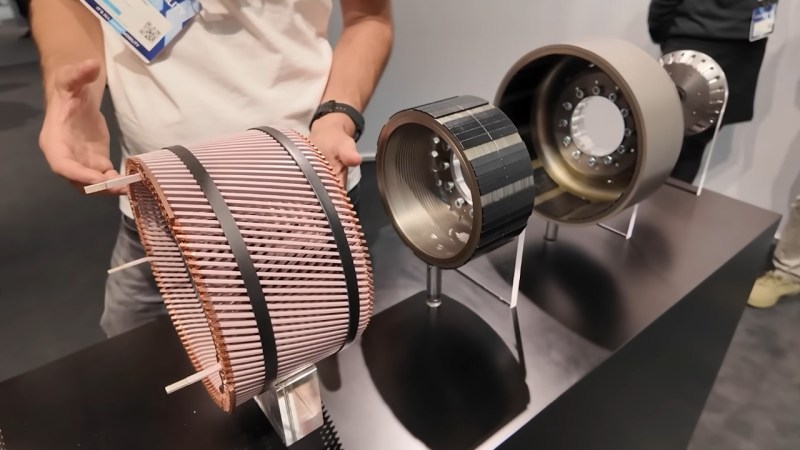

When it comes to building motors, compromise is like that uninvited guest at a dinner party... you just have to deal with it. So, one person's craving for an inrunner electric motor clashes with another's love for outrunners. What do you do? Apparently, you reach for some sort of hybrid solution. It’s like mixing oranges and apples – can’t we just enjoy one fruit?

Honestly, it's all a bit exhausting, isn't it? Sometimes I think it’d just be easier to let them both sit on the shelf—together. Anyway, if you're interested in how these electric motor debates unfold, check it out.

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/09/a-deep-drive-deep-dive-into-a-twin-rotor-motor/

#ElectricMotors #Compromise #EngineeringLife #LazyThoughts #MotorMishaps

Honestly, it's all a bit exhausting, isn't it? Sometimes I think it’d just be easier to let them both sit on the shelf—together. Anyway, if you're interested in how these electric motor debates unfold, check it out.

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/09/a-deep-drive-deep-dive-into-a-twin-rotor-motor/

#ElectricMotors #Compromise #EngineeringLife #LazyThoughts #MotorMishaps

When it comes to building motors, compromise is like that uninvited guest at a dinner party... you just have to deal with it. So, one person's craving for an inrunner electric motor clashes with another's love for outrunners. What do you do? Apparently, you reach for some sort of hybrid solution. It’s like mixing oranges and apples – can’t we just enjoy one fruit?

Honestly, it's all a bit exhausting, isn't it? Sometimes I think it’d just be easier to let them both sit on the shelf—together. Anyway, if you're interested in how these electric motor debates unfold, check it out.

https://hackaday.com/2025/12/09/a-deep-drive-deep-dive-into-a-twin-rotor-motor/

#ElectricMotors #Compromise #EngineeringLife #LazyThoughts #MotorMishaps

0 Comentários

·0 Compartilhamentos