FROM SET TO PIXELS: CINEMATIC ARTISTS COME TOGETHER TO CREATE POETRY

By TREVOR HOGG

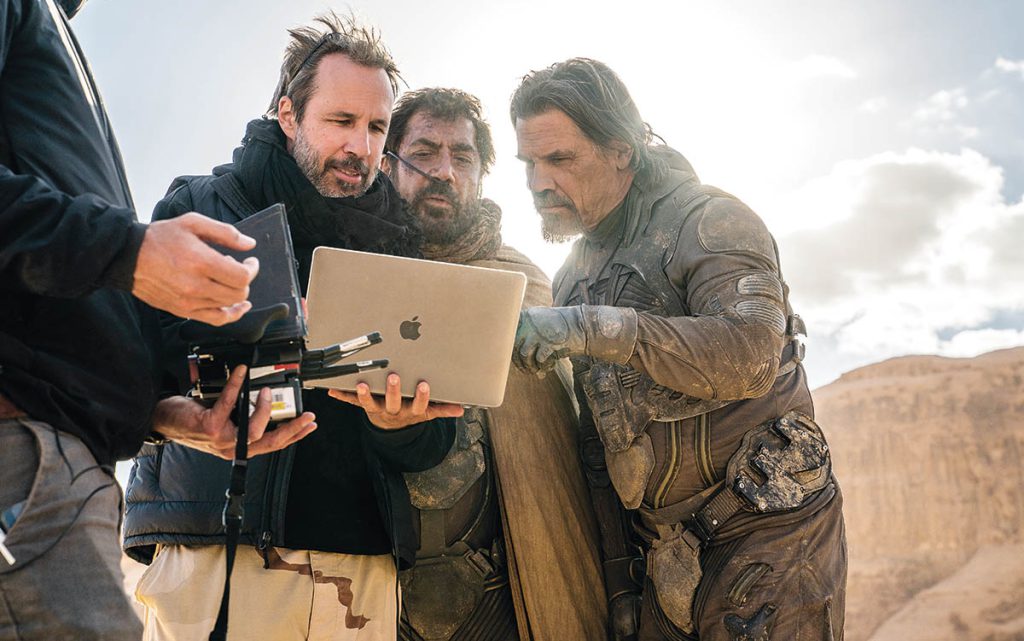

Denis Villeneuvefinds the difficulty of working with visual effects are sometimes the intermediaries between him and the artists and therefore the need to be precise with directions to keep things on track.If post-production has any chance of going smoothly, there must be a solid on-set relationship between the director, cinematographer and visual effects supervisor. “It’s my job to have a vision and to bring it to the screen,” notes Denis Villeneuve, director of Dune: Part Two. “That’s why working with visual effects requires a lot of discipline. It’s not like you work with a keyboard and can change your mind all the time. When I work with a camera, I commit to a mise-en-scène. I’m trying to take the risk, move forward in one direction and enhance it with visual effects. I push it until it looks perfect. It takes a tremendous amount of time and preparation.Paul Lambert is a perfectionist, and I love that about him. We will never put a shot on the screen that we don’t feel has a certain level of quality. It needs to look as real as the face of my actor.”

A legendary cinematographer had a significant influence on how Villeneuve approaches digital augmentation. “Someone I have learned a lot from about visual effects isRoger Deakins. I remember that at the beginning, when I was doing Blade Runner 2049, some artwork was not defined enough, and I was like, ‘I will correct that later.’ Roger said, ‘No. Don’t do that. You have to make sure right at the start.’ I’ve learned the hard way that you need to be as precise as you can, otherwise it goes in a lot of directions.”

Motion capture is visually jarring because your eye is always drawn to the performer in the mocap suit, but it worked out well on Better Man because the same thing happens when he gets replaced by a CG monkey.Visual effects enabled the atmospherics on Wolfs to be art directed, which is not always possible with practical snow.One of the most complex musical numbers in Better Man is “Rock DJ,” which required LiDAR scans of Regent Street and doing full 3D motion capture with the dancers dancing down the whole length of the street to work out how best to shoot it.Cinematographer Dan Mindel favors on-set practical effects because the reactions from the cast come across as being more genuine, which was the case for Twisters.Storyboards are an essential part of the planning process. “When I finish a screenplay, the first thing I do is to storyboard, not just to define the visual element of the movie, but also to rewrite the movie through images,” Villeneuve explains. “Those storyboards inform my crew about the design, costumes, accessories and vehicles, andcreate a visual inner rhythm of the film. This is the first step towards visual effects where there will be a conversation that will start from the boards. That will be translated into previs to help the animators know where we are going because the movie has to be made in a certain timeframe and needs choreography to make sure everybody is moving in the same direction.” The approach towards filmmaking has not changed over the years. “You have a camera and a couple of actors in front of you, and it’s about finding the right angle; the rest is noise. I try to protect the intimacy around the camera as much as possible and focus on that because if you don’t believe the actor, then you won’t believe anything.”

Before transforming singer Robbie Williams into a CG primate, Michael Gracey started as a visual effects artist. “I feel so fortu- nate to have come from a visual effects background early on in my career,” recalls Michael Gracey, director of Better Man. “I would sit down and do all the post myself because I didn’t trust anyone to care as much as I did. Fortunately, over the years I’ve met people who do. It’s a huge part of how I even scrapbook ideas together. Early on, I was constantly throwing stuff up in Flame, doing a video test and asking, ‘Is this going to work?’ Jumping into 3D was something I felt comfortable doing. I’ve been able to plan out or previs ideas. It’s an amazing tool to be armed with if you are a director and have big ideas and you’re trying to convey them to a lot of people.” Previs was pivotal in getting Better Man financed. “Off the page, people were like, ‘Is this monkey even going to work?’ Then they were worried that it wouldn’t work in a musical number. We showed them the previs for Feel, the first musical number, and My Way at the end of the film. I would say, ‘If you get any kind of emotion watching these musical numbers, just imagine what it’s going to be like when it’s filmed and is photoreal.”

Several shots had to be stitched together to create a ‘oner’ that features numerous costume changes and 500 dancers. “For Rock DJ, we were doing LiDAR scans of Regent Street and full 3D motion capture with the dancers dancing down the whole length of the street to work out all of the transition points and how best to shoot it,” Gracey states. “That process involved Erik Wilson, the Cinematographer; Luke Millar, the Visual Effects Supervisor; Ashley Wallen, the Choreographer; and Patrick Correll, Co-Producer. Patrick would sit on set and, in DaVinci Resolve, take the feed from the camera and check every take against the blueprint that we had already previs.” Motion capture is visually jarring to shoot. “Everything that is in-camera looks perfect, then a guy walks in wearing a mocap suit and your eye zooms onto him. But the truth is, your eye does that the moment you replace him with a monkey as well. It worked out quite well because that idea is true to what it is to be famous. A famous person walks into the room and your eye immediately goes to them.”

Digital effects have had a significant impact on a particular area of filmmaking. “Physical effects were a much higher art form than it is now, or it was allowed to be then than it is now,” notes Dan Mindel, Cinematographer on Twisters. “People will decline a real pyrotechnic explosion and do a digital one. But you get a much bigger reaction when there’s actual noise and flash.” It is all about collaboration. Mindel explains, “The principle that I work with is that the visual effects department will make us look great, and we have to give them the raw materials in the best possible form so they can work with it instinctually. Sometimes, as a DP, you might want to do something different, but the bottom line is, you’ve got to listen to these guys, because they know what they want. It gets a bit dogmatic, but most of the time, my relationship with visual effects is good, and especially the guys who have had a foot in the analog world at one point or another and have transitioned into the digital world. When we made Twister, it was an analog movie with digital effects, and it worked great. That’s because everyone on set doing the technical work understood both formats, and we were able to use them well.”

Digital filmmaking has caused a generational gap. “The younger directors don’t think holistically,” Mindel notes. “It’s much more post-driven because they want to manipulate on the Avid or whatever platform it is going to be. What has happened is that the overreaching nature of these tools has left very little to the imagination. A movie that is heavy visual effects is mostly conceptualized on paper using computer-generated graphics and color; that insidiously sneaks into the look and feel of the movie before you know it. You see concept art blasted all over production offices. People could get used to looking at those images, and before you know it, that’s how the movie looks. That’s a very dangerous place to be, not to have the imagination to work around an issue that perhaps doesn’t manifest itself until you’re shooting.” There has to be a sense of purpose. Mindel remarks, “The ability to shoot in a way that doesn’t allow any manipulation in post is the only way to guarantee that there’s just one direction the look can go in. But that could be a little dangerous for some people. Generally, the crowd I’m working with is part of a team, and there’s little thought of taking the movie to a different place than what was shot. I work in the DI with the visual effects supervisor, and we look at our work together so we’re all in agreement that it fits into the movie.”

“All of the advances in technology are a push for greater control,” notes Larkin Seiple, Cinematographer on Everything Everywhere All at Once. “There are still a lot of things that we do with visual effects that we could do practically, but a lot of times it’s more efficient, or we have more attempts at it later in post, than if we had tried to do it practically. I find today, there’s still a debate about what we do on set and what we do later digitally. Many directors have been trying to do more on set, and the best visual effects supervisors I work with push to do everything in-camera as much as possible to make it as realistic as possible.” Storytelling is about figuring out where to invest your time and effort. Seiple states, “I like the adventure of filmmaking. I prefer to go to a mountain top and shoot some of the scenes, get there and be inspired, as opposed to recreate it. Now, if it’s a five-second cutaway, I don’t want production to go to a mountain top and do that. For car work, we’ll shoot the real streets, figure out the time of day and even light the plates for it. Then, I’ll project those on LED walls with actors in a car on a stage. I love doing that because then I get to control how that looks.”

Visual effects have freed Fallout Cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh to shoot quicker and in places that in the past would have been deemed imperfect because of power lines, out-of-period buildings or the sky.Visual effects assist in achieving the desired atmospherics. Seiple says, “On Wolfs, we tried to bring in our own snow for every scene. We would shoot one take, the snow would blow left, and the next take would blow right. Janek Sirrs is probably the best visual effects supervisor I’ve worked with, and he was like, ‘Please turn off the snow. It’ll be a nightmare trying to remove the snow from all these shots then add our own snow back for continuity because you can’t have the snow changing direction every other cut.’ Or we’d have to ‘snow’ a street, which would take ages. Janek would say, ‘Let’s put enough snow on the ground to see the lighting on it and where the actors walk. We’ll do the rest of the street later because we have a perfect reference of what it should look like.” Certain photographic principles have to be carried over into post-production to make shots believable to the eye. Seiple explains, “When you make all these amazing details that should be out of focus sharper, then the image feels like a visual effect because it doesn’t work the way a lens would work.” Familiarity with the visual effects process is an asset in being able to achieve the best result. “I inadvertently come from a lot of visual effect-heavy shoots and shows, so I’m quick to have an opinion about it. Many directors love to reference the way David Fincher uses visual effects because there is such great behind-the-scenes imagery that showcases how they were able to do simple things. Also, I like to shoot tests even on an iPhone to see if this comp will work or if this idea is a good one.”

Cinematographer Fabian Wagner and VFX Supervisor John Moffatt spent a lot of time in pre-production for Venom: The Last Dance discussing how to bring out the texture of the symbiote through lighting and camera angles.Game of Thrones Director of Photography Fabian Wagner had to make key decisions while prepping and breaking down the script so visual effects had enough time to meet deadline.Twisters was an analog movie with digital effects that worked well because everyone on set doing the technical work understood both formats.For Cinematographer Larkin Seiple, storytelling is about figuring out where to invest your time and effort. Scene from the Netflix series Beef.Cinematographer Larkin Seiple believes that all of the advances in technology are a push for greater control, which occurred on Everything Everywhere All at Once.Nothing beats reality when it comes to realism. “Every project I do I talk more about the real elements to bring into the shoot than the visual effect element because the more practical stuff that you can do on set, the more it will embed the visual effects into the image, and, therefore, they’re more real,” observes Fabian Wagner, Cinematographer on Venom: The Last Dance. “It also depends on the job you’re doing in terms of how real or unreal you want it to be. Game of Thrones was a good example because it was a visual effects-heavy show, but they were keen on pushing the reality of things as much as possible. We were doing interactive lighting and practical on-set things to embed the visual effects. It was successful.” Television has a significantly compressed schedule compared to feature films. “There are fewer times to iterate. You have to be much more precise. On Game of Thrones, we knew that certain decisions had to be made early on while we were still prepping and breaking down the script. Because of their due dates, to be ready in time, they had to start the visual effects process for certain dragon scenes months before we even started shooting.”

“Like everything else, it’s always about communication,” Wagner notes. “I’ve been fortunate to work with extremely talented and collaborative visual effects supervisors, visual effects producers and directors. I have become friends with most of those visual effects departments throughout the shoot, so it’s easy to stay in touch. Even when Venom: The Last Dance was posting, I would be talking to John Moffatt, who was our talented visual effects supervisor. We would exchange emails, text messages or phone calls once a week, and he would send me updates, which we would talk about it. If I gave any notes or thoughts, John would listen, and if it were possible to do anything about, he would. In the end, it’s about those personal relationships, and if you have those, that can go a long way.” Wagner has had to deal with dragons, superheroes and symbiotes. “They’re all the same to me! For the symbiote, we had two previous films to see what they had done, where they had succeeded and where we could improve it slightly. While prepping, John and I spent a lot of time talking about how to bring out the texture of the symbiote and help it with the lighting and camera angles. One of the earliest tests was to see what would happen if we backlit or side lit it as well as trying different textures for reflections. We came up with something we all were happy with, and that’s what we did on set. It was down to trying to speak the same language and aiming for the same thing, which in this case was, ‘How could we make the symbiote look the coolest?’”

Visual effects has become a crucial department throughout the filmmaking process. “The relationship with the visual effects supervisor is new,” states Stuart Dryburgh, Cinematographer on Fallout. “We didn’t really have that. On The Piano, the extent of the visual effects was having somebody scribbling in a lightning strike over a stormy sky and a little flash of an animated puppet. Runaway Bride had a two-camera setup where one of the cameras pushed into the frame, and that was digitally removed, but we weren’t using it the way we’re using it now. ForEast of Eden, we’re recreating 19th and early 20th century Connecticut, Boston and Salinas, California in New Zealand. While we have some great sets built and historical buildings that we can use, there is a lot of set extension and modification, and some complete bluescreen scenes, which allow us to more realistically portray a historical environment than we could have done back in the day.” The presence of a visual effects supervisor simplified principal photography. Dryburgh adds, “In many ways, using visual effects frees you to shoot quicker and in places that might otherwise be deemed imperfect because of one little thing, whether it’s power lines or out-of-period buildings or sky. All of those can be easily fixed. Most of us have been doing it for long enough that we have a good idea of what can and can’t be done and how it’s done so that the visual effects supervisor isn’t the arbiter.”

Lighting cannot be arbitrarily altered in post as it never looks right. “Whether you set the lighting on the set and the background artist has to match that, or you have an existing background and you, as a DP, have to match that – that is the lighting trick to the whole thing,” Dryburgh observes. “Everything has to be the same, a soft or hard light, the direction and color. Those things all need to line up in a composited shot; that is crucial.” Every director has his or her own approach to filmmaking. “Harold Ramis told me, ‘I’ll deal with the acting and the words. You just make it look nice, alright?’ That’s the conversation we had about shots, and it worked out well.Garth Davis, who I’m working with now, is a terrific photographer in his own right and has a great visual sense, so he’s much more involved in anything visual, whether it be the designs of the sets, creation of the visual effects, my lighting or choice of lenses. It becomes much more collaborative. And that applies to the visual effects department as well.” Recreating vintage lenses digitally is an important part of the visual aesthetic. “As digital photography has become crisper, better and sharper, people have chosen to use fewer perfect optics, such as lenses that are softer on the edges or give a flare characteristic. Before production, we have the camera department shoot all of these lens grids of different packages and ranges, and visual effects takes that information so they can model every lens. If they’re doing a fully CG background, they can apply that lens characteristic,” remarks Dryburgh.

Television schedules for productions like House of the Dragon do not allow a lot of time to iterate, so decisions have to be precise.Bluescreen and stunt doubles on Twisters.“The principle that I work with is that the visual effects department will make us look great, and we have to give them the raw materials in the best possible form so they can work with it instinctually. Sometimes, as a DP, you might want to do something different, but the bottom line is, you’ve got to listen to these guys because they know what they want. It gets a bit dogmatic, but most of the time, my relationship with visual effects is good, and especially the guys who have had a foot in the analog world at one point or another and have transitioned into the digital world.”

—Dan Mindel, Cinematographer, Twisters

Cinematographers like Greig Fraser have adopted Unreal Engine. “Greig has an incredible curiosity about new technology, and that helped us specifically with Dune: Part Two,” Villeneuve explains. “Greig was using Unreal Engine to capture natural environments. For example, if we decide to shoot in that specific rocky area, we’ll capture the whole area with drones to recreate the terrain in the computer. If I said, ‘I want to shoot in that valley on November 3rd and have the sun behind the actors. At what time is it? You have to be there at 9:45 am.’ We built the whole schedule like a puzzle to maximize the power of natural light, but that came through those studies, which were made with the software usually used for video games.” Technology is essentially a tool that keeps evolving. Villeneuve adds, “Sometimes, I don’t know if I feel like a dinosaur or if my last movie will be done in this house behind the computer alone. It would be much less tiring to do that, but seriously, the beauty of cinema is the idea of bringing many artists together to create poetry.”

#set #pixels #cinematic #artists #come

FROM SET TO PIXELS: CINEMATIC ARTISTS COME TOGETHER TO CREATE POETRY

By TREVOR HOGG

Denis Villeneuvefinds the difficulty of working with visual effects are sometimes the intermediaries between him and the artists and therefore the need to be precise with directions to keep things on track.If post-production has any chance of going smoothly, there must be a solid on-set relationship between the director, cinematographer and visual effects supervisor. “It’s my job to have a vision and to bring it to the screen,” notes Denis Villeneuve, director of Dune: Part Two. “That’s why working with visual effects requires a lot of discipline. It’s not like you work with a keyboard and can change your mind all the time. When I work with a camera, I commit to a mise-en-scène. I’m trying to take the risk, move forward in one direction and enhance it with visual effects. I push it until it looks perfect. It takes a tremendous amount of time and preparation.Paul Lambert is a perfectionist, and I love that about him. We will never put a shot on the screen that we don’t feel has a certain level of quality. It needs to look as real as the face of my actor.”

A legendary cinematographer had a significant influence on how Villeneuve approaches digital augmentation. “Someone I have learned a lot from about visual effects isRoger Deakins. I remember that at the beginning, when I was doing Blade Runner 2049, some artwork was not defined enough, and I was like, ‘I will correct that later.’ Roger said, ‘No. Don’t do that. You have to make sure right at the start.’ I’ve learned the hard way that you need to be as precise as you can, otherwise it goes in a lot of directions.”

Motion capture is visually jarring because your eye is always drawn to the performer in the mocap suit, but it worked out well on Better Man because the same thing happens when he gets replaced by a CG monkey.Visual effects enabled the atmospherics on Wolfs to be art directed, which is not always possible with practical snow.One of the most complex musical numbers in Better Man is “Rock DJ,” which required LiDAR scans of Regent Street and doing full 3D motion capture with the dancers dancing down the whole length of the street to work out how best to shoot it.Cinematographer Dan Mindel favors on-set practical effects because the reactions from the cast come across as being more genuine, which was the case for Twisters.Storyboards are an essential part of the planning process. “When I finish a screenplay, the first thing I do is to storyboard, not just to define the visual element of the movie, but also to rewrite the movie through images,” Villeneuve explains. “Those storyboards inform my crew about the design, costumes, accessories and vehicles, andcreate a visual inner rhythm of the film. This is the first step towards visual effects where there will be a conversation that will start from the boards. That will be translated into previs to help the animators know where we are going because the movie has to be made in a certain timeframe and needs choreography to make sure everybody is moving in the same direction.” The approach towards filmmaking has not changed over the years. “You have a camera and a couple of actors in front of you, and it’s about finding the right angle; the rest is noise. I try to protect the intimacy around the camera as much as possible and focus on that because if you don’t believe the actor, then you won’t believe anything.”

Before transforming singer Robbie Williams into a CG primate, Michael Gracey started as a visual effects artist. “I feel so fortu- nate to have come from a visual effects background early on in my career,” recalls Michael Gracey, director of Better Man. “I would sit down and do all the post myself because I didn’t trust anyone to care as much as I did. Fortunately, over the years I’ve met people who do. It’s a huge part of how I even scrapbook ideas together. Early on, I was constantly throwing stuff up in Flame, doing a video test and asking, ‘Is this going to work?’ Jumping into 3D was something I felt comfortable doing. I’ve been able to plan out or previs ideas. It’s an amazing tool to be armed with if you are a director and have big ideas and you’re trying to convey them to a lot of people.” Previs was pivotal in getting Better Man financed. “Off the page, people were like, ‘Is this monkey even going to work?’ Then they were worried that it wouldn’t work in a musical number. We showed them the previs for Feel, the first musical number, and My Way at the end of the film. I would say, ‘If you get any kind of emotion watching these musical numbers, just imagine what it’s going to be like when it’s filmed and is photoreal.”

Several shots had to be stitched together to create a ‘oner’ that features numerous costume changes and 500 dancers. “For Rock DJ, we were doing LiDAR scans of Regent Street and full 3D motion capture with the dancers dancing down the whole length of the street to work out all of the transition points and how best to shoot it,” Gracey states. “That process involved Erik Wilson, the Cinematographer; Luke Millar, the Visual Effects Supervisor; Ashley Wallen, the Choreographer; and Patrick Correll, Co-Producer. Patrick would sit on set and, in DaVinci Resolve, take the feed from the camera and check every take against the blueprint that we had already previs.” Motion capture is visually jarring to shoot. “Everything that is in-camera looks perfect, then a guy walks in wearing a mocap suit and your eye zooms onto him. But the truth is, your eye does that the moment you replace him with a monkey as well. It worked out quite well because that idea is true to what it is to be famous. A famous person walks into the room and your eye immediately goes to them.”

Digital effects have had a significant impact on a particular area of filmmaking. “Physical effects were a much higher art form than it is now, or it was allowed to be then than it is now,” notes Dan Mindel, Cinematographer on Twisters. “People will decline a real pyrotechnic explosion and do a digital one. But you get a much bigger reaction when there’s actual noise and flash.” It is all about collaboration. Mindel explains, “The principle that I work with is that the visual effects department will make us look great, and we have to give them the raw materials in the best possible form so they can work with it instinctually. Sometimes, as a DP, you might want to do something different, but the bottom line is, you’ve got to listen to these guys, because they know what they want. It gets a bit dogmatic, but most of the time, my relationship with visual effects is good, and especially the guys who have had a foot in the analog world at one point or another and have transitioned into the digital world. When we made Twister, it was an analog movie with digital effects, and it worked great. That’s because everyone on set doing the technical work understood both formats, and we were able to use them well.”

Digital filmmaking has caused a generational gap. “The younger directors don’t think holistically,” Mindel notes. “It’s much more post-driven because they want to manipulate on the Avid or whatever platform it is going to be. What has happened is that the overreaching nature of these tools has left very little to the imagination. A movie that is heavy visual effects is mostly conceptualized on paper using computer-generated graphics and color; that insidiously sneaks into the look and feel of the movie before you know it. You see concept art blasted all over production offices. People could get used to looking at those images, and before you know it, that’s how the movie looks. That’s a very dangerous place to be, not to have the imagination to work around an issue that perhaps doesn’t manifest itself until you’re shooting.” There has to be a sense of purpose. Mindel remarks, “The ability to shoot in a way that doesn’t allow any manipulation in post is the only way to guarantee that there’s just one direction the look can go in. But that could be a little dangerous for some people. Generally, the crowd I’m working with is part of a team, and there’s little thought of taking the movie to a different place than what was shot. I work in the DI with the visual effects supervisor, and we look at our work together so we’re all in agreement that it fits into the movie.”

“All of the advances in technology are a push for greater control,” notes Larkin Seiple, Cinematographer on Everything Everywhere All at Once. “There are still a lot of things that we do with visual effects that we could do practically, but a lot of times it’s more efficient, or we have more attempts at it later in post, than if we had tried to do it practically. I find today, there’s still a debate about what we do on set and what we do later digitally. Many directors have been trying to do more on set, and the best visual effects supervisors I work with push to do everything in-camera as much as possible to make it as realistic as possible.” Storytelling is about figuring out where to invest your time and effort. Seiple states, “I like the adventure of filmmaking. I prefer to go to a mountain top and shoot some of the scenes, get there and be inspired, as opposed to recreate it. Now, if it’s a five-second cutaway, I don’t want production to go to a mountain top and do that. For car work, we’ll shoot the real streets, figure out the time of day and even light the plates for it. Then, I’ll project those on LED walls with actors in a car on a stage. I love doing that because then I get to control how that looks.”

Visual effects have freed Fallout Cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh to shoot quicker and in places that in the past would have been deemed imperfect because of power lines, out-of-period buildings or the sky.Visual effects assist in achieving the desired atmospherics. Seiple says, “On Wolfs, we tried to bring in our own snow for every scene. We would shoot one take, the snow would blow left, and the next take would blow right. Janek Sirrs is probably the best visual effects supervisor I’ve worked with, and he was like, ‘Please turn off the snow. It’ll be a nightmare trying to remove the snow from all these shots then add our own snow back for continuity because you can’t have the snow changing direction every other cut.’ Or we’d have to ‘snow’ a street, which would take ages. Janek would say, ‘Let’s put enough snow on the ground to see the lighting on it and where the actors walk. We’ll do the rest of the street later because we have a perfect reference of what it should look like.” Certain photographic principles have to be carried over into post-production to make shots believable to the eye. Seiple explains, “When you make all these amazing details that should be out of focus sharper, then the image feels like a visual effect because it doesn’t work the way a lens would work.” Familiarity with the visual effects process is an asset in being able to achieve the best result. “I inadvertently come from a lot of visual effect-heavy shoots and shows, so I’m quick to have an opinion about it. Many directors love to reference the way David Fincher uses visual effects because there is such great behind-the-scenes imagery that showcases how they were able to do simple things. Also, I like to shoot tests even on an iPhone to see if this comp will work or if this idea is a good one.”

Cinematographer Fabian Wagner and VFX Supervisor John Moffatt spent a lot of time in pre-production for Venom: The Last Dance discussing how to bring out the texture of the symbiote through lighting and camera angles.Game of Thrones Director of Photography Fabian Wagner had to make key decisions while prepping and breaking down the script so visual effects had enough time to meet deadline.Twisters was an analog movie with digital effects that worked well because everyone on set doing the technical work understood both formats.For Cinematographer Larkin Seiple, storytelling is about figuring out where to invest your time and effort. Scene from the Netflix series Beef.Cinematographer Larkin Seiple believes that all of the advances in technology are a push for greater control, which occurred on Everything Everywhere All at Once.Nothing beats reality when it comes to realism. “Every project I do I talk more about the real elements to bring into the shoot than the visual effect element because the more practical stuff that you can do on set, the more it will embed the visual effects into the image, and, therefore, they’re more real,” observes Fabian Wagner, Cinematographer on Venom: The Last Dance. “It also depends on the job you’re doing in terms of how real or unreal you want it to be. Game of Thrones was a good example because it was a visual effects-heavy show, but they were keen on pushing the reality of things as much as possible. We were doing interactive lighting and practical on-set things to embed the visual effects. It was successful.” Television has a significantly compressed schedule compared to feature films. “There are fewer times to iterate. You have to be much more precise. On Game of Thrones, we knew that certain decisions had to be made early on while we were still prepping and breaking down the script. Because of their due dates, to be ready in time, they had to start the visual effects process for certain dragon scenes months before we even started shooting.”

“Like everything else, it’s always about communication,” Wagner notes. “I’ve been fortunate to work with extremely talented and collaborative visual effects supervisors, visual effects producers and directors. I have become friends with most of those visual effects departments throughout the shoot, so it’s easy to stay in touch. Even when Venom: The Last Dance was posting, I would be talking to John Moffatt, who was our talented visual effects supervisor. We would exchange emails, text messages or phone calls once a week, and he would send me updates, which we would talk about it. If I gave any notes or thoughts, John would listen, and if it were possible to do anything about, he would. In the end, it’s about those personal relationships, and if you have those, that can go a long way.” Wagner has had to deal with dragons, superheroes and symbiotes. “They’re all the same to me! For the symbiote, we had two previous films to see what they had done, where they had succeeded and where we could improve it slightly. While prepping, John and I spent a lot of time talking about how to bring out the texture of the symbiote and help it with the lighting and camera angles. One of the earliest tests was to see what would happen if we backlit or side lit it as well as trying different textures for reflections. We came up with something we all were happy with, and that’s what we did on set. It was down to trying to speak the same language and aiming for the same thing, which in this case was, ‘How could we make the symbiote look the coolest?’”

Visual effects has become a crucial department throughout the filmmaking process. “The relationship with the visual effects supervisor is new,” states Stuart Dryburgh, Cinematographer on Fallout. “We didn’t really have that. On The Piano, the extent of the visual effects was having somebody scribbling in a lightning strike over a stormy sky and a little flash of an animated puppet. Runaway Bride had a two-camera setup where one of the cameras pushed into the frame, and that was digitally removed, but we weren’t using it the way we’re using it now. ForEast of Eden, we’re recreating 19th and early 20th century Connecticut, Boston and Salinas, California in New Zealand. While we have some great sets built and historical buildings that we can use, there is a lot of set extension and modification, and some complete bluescreen scenes, which allow us to more realistically portray a historical environment than we could have done back in the day.” The presence of a visual effects supervisor simplified principal photography. Dryburgh adds, “In many ways, using visual effects frees you to shoot quicker and in places that might otherwise be deemed imperfect because of one little thing, whether it’s power lines or out-of-period buildings or sky. All of those can be easily fixed. Most of us have been doing it for long enough that we have a good idea of what can and can’t be done and how it’s done so that the visual effects supervisor isn’t the arbiter.”

Lighting cannot be arbitrarily altered in post as it never looks right. “Whether you set the lighting on the set and the background artist has to match that, or you have an existing background and you, as a DP, have to match that – that is the lighting trick to the whole thing,” Dryburgh observes. “Everything has to be the same, a soft or hard light, the direction and color. Those things all need to line up in a composited shot; that is crucial.” Every director has his or her own approach to filmmaking. “Harold Ramis told me, ‘I’ll deal with the acting and the words. You just make it look nice, alright?’ That’s the conversation we had about shots, and it worked out well.Garth Davis, who I’m working with now, is a terrific photographer in his own right and has a great visual sense, so he’s much more involved in anything visual, whether it be the designs of the sets, creation of the visual effects, my lighting or choice of lenses. It becomes much more collaborative. And that applies to the visual effects department as well.” Recreating vintage lenses digitally is an important part of the visual aesthetic. “As digital photography has become crisper, better and sharper, people have chosen to use fewer perfect optics, such as lenses that are softer on the edges or give a flare characteristic. Before production, we have the camera department shoot all of these lens grids of different packages and ranges, and visual effects takes that information so they can model every lens. If they’re doing a fully CG background, they can apply that lens characteristic,” remarks Dryburgh.

Television schedules for productions like House of the Dragon do not allow a lot of time to iterate, so decisions have to be precise.Bluescreen and stunt doubles on Twisters.“The principle that I work with is that the visual effects department will make us look great, and we have to give them the raw materials in the best possible form so they can work with it instinctually. Sometimes, as a DP, you might want to do something different, but the bottom line is, you’ve got to listen to these guys because they know what they want. It gets a bit dogmatic, but most of the time, my relationship with visual effects is good, and especially the guys who have had a foot in the analog world at one point or another and have transitioned into the digital world.”

—Dan Mindel, Cinematographer, Twisters

Cinematographers like Greig Fraser have adopted Unreal Engine. “Greig has an incredible curiosity about new technology, and that helped us specifically with Dune: Part Two,” Villeneuve explains. “Greig was using Unreal Engine to capture natural environments. For example, if we decide to shoot in that specific rocky area, we’ll capture the whole area with drones to recreate the terrain in the computer. If I said, ‘I want to shoot in that valley on November 3rd and have the sun behind the actors. At what time is it? You have to be there at 9:45 am.’ We built the whole schedule like a puzzle to maximize the power of natural light, but that came through those studies, which were made with the software usually used for video games.” Technology is essentially a tool that keeps evolving. Villeneuve adds, “Sometimes, I don’t know if I feel like a dinosaur or if my last movie will be done in this house behind the computer alone. It would be much less tiring to do that, but seriously, the beauty of cinema is the idea of bringing many artists together to create poetry.”

#set #pixels #cinematic #artists #come