A New Picture of Schizophrenia Emerges, and So Do New Ways to Treat It

www.scientificamerican.com

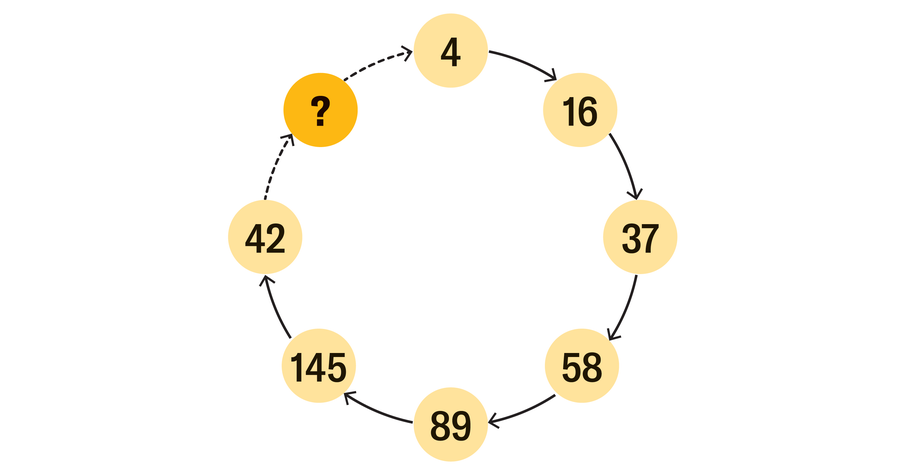

March 18, 202513 min readNew Treatments Are Rewriting Our Understanding of SchizophreniaAs a complex picture of schizophrenia emerges, so do new ways to treat the disorderBy Diana Kwon edited by Madhusree Mukerjee Galen DaraCharlene Sunkel was 19 when she started hearing voices and strange thoughts began filling her head. People wanted to infiltrate her mind, to poison her, to rat her out to the police. She stopped making eye contact, convinced that it would enable others to steal her thoughts. Once sociable and outgoing, Sunkel withdrew from friends and family, worried that they were conspiring against her. On her way to work, she had visions of men in hoods from the corner of her eye. As the illness progressed, she lost the ability to understand what people were saying, and when she spoke, the words would not come out right. About a year after her symptoms started, Sunkel was diagnosed with schizophrenia.Delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking are collectively known as psychosis. These positive symptoms are among the most widely recognized aspects of schizophrenia. For about two thirds of patients with schizophreniawhich affects approximately 23 million people around the worldtraditional antipsychotic drugs are often highly effective at treating psychosis. But these drugs frequently come with problematic side effects. And they do little to help with the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as emotional flatness and social withdrawal, or with other issues involving thinking and memory referred to as cognitive problems.Until quite recently, all antipsychotics worked in essentially the same way. They blocked the activity of dopamine, a chemical messenger in the brain involved in motivation, learning, habit formation, and other processes.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.But the arrival last September of a new drug, KarXT, supports an emerging awareness among clinicians that schizophrenia is more complex than most of them had realized. KarXT is the first antipsychotic to target a molecule other than dopamine. It may be a key aspect of the disorder in some people, but dopamine is just one of many different neurotransmitters involved in the illness. That complexity may provide fresh avenues for treatment.There is no schizophrenia. There are schizophrenias. Romina Mizrahi, professor of psychiatryTo Thomas Kabir, a senior researcher at the University of Oxford with a lived experience of psychosis, KarXTs potential to not only reduce symptoms of psychosis but also improve thinking is especially exciting. People typically dont have hallucinations and delusions for years on end, he says. It is the cognitive issues that really affect peoples day-to-day lives.Perhaps most significant, a growing body of evidence suggests that schizophrenia, which can involve alterations not only in the brain but also in the bodyparticularly in the immune systemdoes not look the same in everyone who has the condition. There is no schizophrenia. There are schizophrenias, says Romina Mizrahi, a professor of psychiatry at McGill University. What clinicians need now, she adds, is a way to categorize individuals based on the underlying biology of their illness so that treatments can be better tailored to their needs.Scientists have been trying to understand the neurobiological underpinnings of schizophrenia for more than a century. German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, who in 1893 penned one of the earliest official descriptions of schizophrenia, called it dementia praecox, meaning premature dementia. Because the condition tends to show up in adolescents or young adults, Kraepelin held that schizophrenia was a neurodegenerative disease, similar to those that often afflict the elderly.In contrast, Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, whose long hours with patients at the Rheinau psychiatric hospital in Zurich led to more than a decades worth of meticulous notes about their behavior, held that the disorder did not always involve progressive deterioration or begin solely in adolescence. In 1908 he coined the term schizophrenia, meaning split mind, to characterize the fragmentation of mental functions that he saw as central to the condition.Bleuler was prescient in other ways. He referred to the group of schizophrenias, reflecting his view that it was a collection of disorders with a range of severity, a spectrum of symptoms and variable outcomes. And he postulated that the ailments have both a biological and a psychological basis. The tendency for schizophrenia to run in families has since been documentedthe disorder is about 80 percent heritable. But specific genes have been difficult to pin down, and researchers suspect hundreds of them might be involved. Many studies also point to the importance of the environment. Adverse experiences in childhood, being exposed to infections in the womb, growing up in cities and heavy cannabis use all contribute to increased risk.Despite growing evidence of schizophrenia being rooted in changes occurring during childhood, Kraepelins idea that schizophrenia is neurodegenerative persistsalthough it is hotly debated. In some patients, symptoms worsen over time, and this progression is often accompanied by tissue loss in the brain. Several researchers have argued that this deterioration can instead be attributed to factors secondary to the illness, such as poverty and stress.When antipsychotic drugs first emerged, they seemed to drastically simplify the picture. In the 1950s a pair of psychiatrists in France discovered serendipitously that chlorpromazine, a compound designed to be an anesthetic for surgery, helped to address hallucinations and delusions. Chlorpromazine and the other antipsychotics that followed brought an end to an era of crude and often dangerous treatments for schizophrenia, such as lobotomies.At first, no one knew why chlorpromazine and its derivatives worked. Later studies in mice revealed that these medications blocked receptors for dopamine. (Receptors are molecules that serve as code-locked doors, allowing only certain molecules, in this case dopamine, to enter a cell.) These findings, along with observations that high doses of amphetaminesdrugs known to release dopaminecan cause short-term psychosis in healthy people, paved the way for the so-called dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. It posits that the symptoms of schizophrenia are caused by an excess of dopamine in the brain.Though effective at treating psychosis, dopamine blockers are no panacea for schizophrenia. They come with a host of side effects, such as tremors resembling those in Parkinsons patients (who suffer from a paucity of dopamine), sedation, and significant weight gain that can subsequently lead to an increased risk of diabetes and heart problems. In fact, cardiovascular disease is one of the most common causes of death in people with schizophrenia who have a long history of using dopamine blockers.Ni-ka Ford; Source: Schizophrenia: From Neurochemistry to Circuits, Symptoms and Treatments, by Oliver D. Howes et al., in Nature Reviews Neurology, Vol. 20; December 2023 (reference)In the years after her diagnosis, Sunkel was hospitalized multiple times and prescribed many different medications that came with debilitating side effects, including intense restlessness, tremors and sedation. One drug led to spasms so severe that she was unable to move or speak. Though deemed treatment-resistant, a label given to people whose symptoms do not improve after two or more drugs, Sunkel ultimately found clozapine, a dopamine-blocking antipsychotic.Despite its side effects, the medication has significantly helped to improve her quality of life, says Sunkel, who is now in her 50s and working as chief executive officer of the Global Mental Health Peer Network in South Africa. But in up to 60 percent of people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, clozapine, too, can be ineffective.For decades the only available antipsychotic drugs were dopamine blockers. From the 1990s onward, however, researchers began employing techniques such as positron-emission tomography (PET), an imaging method that enables them to view the activity of specific molecules inside the living brain. That work suggested a more complicated story.Neuroscientists used PET imaging and other means to identify neurochemical alterations in the brain that are associated with schizophrenia. They found dopamine activity to be increased in a specific region of the striatum, a structure located deep in the brain that is largely involved in helping us forge mental links between disparate events or things. This anomaly may increase the chances of someone with schizophrenia making false associations or having misperceptions. In addition, scientists discovered that dopamine levels are lowered in the prefrontal cortex, thereby interfering with executive functions such as problem-solving and emotion regulation, which can be impaired in people with the condition.These studies also shed light on why antipsychotics dont always work. In 2012 Oliver Howes, a professor of molecular psychiatry at Kings College London, and his team reported that people who do not respond to traditional antipsychotics have different patterns of dopamine activity in the brain than those who do respond.Such investigations established that dopamine is not the only neurotransmitter involved in schizophrenia. Others include glutamate, a key molecule involved in activating neurons. A group led by psychiatrist John Krystal of the Yale School of Medicine, as well as others, has demonstrated that ketaminea drug that blocks the activity of glutamatecan produce symptoms of psychosis in healthy people. Large-scale searches for genetic variants associated with schizophrenia have also revealed that alterations in genes involved in glutamate signaling are among the key risk factors for developing the disorder. In recent decades many glutamate-targeting drugs have been developed, but none have yet made it through clinical trials.Another key neurotransmitter, called acetylcholine, acts on muscarinic receptors found throughout both the body and the brain that are involved in such processes as movement, memory and learning. The new schizophrenia drug, KarXT, which is marketed and sold as Cobenfy by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), selectively activates muscarinic receptors in the brain. In clinical trials, the drug was found to be effective in treating psychosis and seemed to improve cognitive function, without the side effects that make traditional antipsychotics difficult for patients to remain on for long periods. The drug did have gastrointestinal effects, most of which were mild.KarXT is the first antipsychotic to target a molecule other than dopamine.Although more data are needed on the long-term effects of KarXT, the drug has enthused researchers in the schizophrenia fieldThere is indeed another, startlingly different way in which schizophrenia can arise. April Burrell was a healthy, vibrant 21-year-old until a traumatic event changed everything. She developed psychosis and hallucinations and eventually went into a completely catatonic state, unable to move or communicate. She was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia and admitted to the Pilgrim Psychiatric Center in Brentwood, N.Y., where she would spend nearly 20 years.It was only when Sander Markx, a psychiatrist at Pilgrim, gathered a multidisciplinary team and ordered a full medical workup that Burrells doctors discovered her blood contained autoantibodiesantibodies that were attacking her own body, damaging cells in her brain. She received a new diagnosis of neuropsychiatric lupus, an autoimmune disease. After six months of an intensive immunosuppressive treatment regimen, Burrell made an almost full recovery in 2020. You wouldve thought she was a brand-new person, her brother, Guy Burrell, told the Washington Post in 2023.Autoimmune encephalitis, a disease that occurs when the bodys own immune system attacks the brain, was discovered less than two decades ago. Before it was known, many of the people with this illness would havelike Burrellreceived a diagnosis of schizophrenia despite some subtle differences between the two conditions. In people with autoimmune encephalitis, for example, symptoms tend to appear more rapidly and be more severe.Some of the first cases of autoimmune encephalitis were reported in 2007. Josep Dalmau, a neurologist then at the University of Pennsylvania, and his colleagues published descriptions of patients who had autoantibodies against the NMDA receptor, the protein in the brain on which glutamateone of the key neurotransmitters that are altered in people with schizophreniaexerts its action. In the years since, researchers have documented more than two dozen autoantibodies that target the brain. A diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis, which often requires the detection of autoantibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the liquid washing through the brain and spinal cord, can be life-changing. Some patients who receive immunotherapy make a full recovery.Clear-cut cases of autoimmune encephalitis are rare. According to some estimates, about 1 percent of people with psychosis have autoantibodies whose specific target in the brain has been identified. But determining the true prevalence is difficult because lumbar punctures, which are required to obtain CSF, are rarely carried out in psychiatry clinics, where most people with psychosis go for treatment.According to psychiatrist Ludger Tebartz van Elst of the University of Freiburg and its associated hospital in Germany, where lumbar punctures for people with psychosis are routine, his team has found uncharacterized neuronal autoantibodies (meaning autoantibodies that are not clearly established as causes of psychosis) in approximately 20 percent of patients with psychosis and other psychiatric conditions. Accordingly, Tebartz van Elst and others advocate using the term autoimmune psychosis to describe the ailments of these patients.Researchers are now studying whether the immune system might be at play in a greater proportion of people who receive a schizophrenia diagnosis.The question of whether these nonspecific autoantibodies might play a meaningful role in schizophrenia and other disorders of psychosis has been a matter of intense debate in recent years. Studies of their prevalence in people with psychosiswhich often examine blood because CSF is not always obtainablehave turned up inconsistent results. Researchers have also found these antibodies in healthy people, raising doubts about their clinical significance.Others believe the immune system might contribute to psychosis even in the absence of autoantibodies. Cases of psychosis triggered by infections such as influenza, syphilis and, more recently, COVID-19 are scattered throughout history. In addition, epidemiological studies have reported a greater number of mental disorders such as schizophrenia in people who are born in the winter, when infections are more prevalent, compared with those born in the summer. Assessments from countries that keep national registries of medical data, such as Denmark, have revealed that the more infections a person has, the higher their risk of developing schizophrenia.Whether infections can directly cause psychosis remains uncertain, but over the years many studies have provided evidence for the immune system being the culprit. Genomic investigations of people with schizophrenia have implicated genes linked to key proteins involved in the immune system. Further, the brains resident immune cells, the microglia, are overactive in people with schizophrenia, leading some scientists to suggest that they are involved in the disorder.Researchers are now studying whether the immune system might be at play in a greater proportion of people who receive a schizophrenia diagnosis. Some groups are conducting clinical trials to investigate whether immunotherapies could help people with schizophrenia and other psychosis-related disorders who do not meet the criteria for an autoimmune disease.At Oxford, Kabir, psychiatry professor Belinda Lennox and their colleagues are currently conducting a clinical trial to examine whether rituximab, an antibody used to treat arthritis and other autoimmune disorders, can effectively treat psychosis in people who have detectable neuronal autoantibodies in their blood. Janet Cunningham, a psychiatrist at Uppsala University in Sweden, and her team are carrying out a similar study in that country. If even a small percentage of these individuals respond to these therapies, it would be transformative, Lennox says, because you can potentially cure their lifelong illness.There is much excitement around the possibility of immunotherapies for psychosis, although experts caution against focusing solely on the immune underpinnings of the disorder. Patients can sometimes see autoimmune psychosis as a more palatable diagnosis than schizophrenia because it may provide a more promising road to recoveryand because it avoids the stigma surrounding the word schizophrenia. But immunotherapies are not without their risks. Medications such as cortisone, which are often used in cases of autoimmune psychosis, come with their own side effects, including bone fragility, slow wound healing, and psychological effects such as mood swings and confusion.Cunningham says its important to remember that existing antipsychotics do help many people with schizophrenia and other psychosis-related disorders. Weve gotten to the point where a lot of people are being helped with the medication we have, she says. Now we have to be looking at the ones we are not able to help.Kabir, the Oxford researcher who has lived experience of psychosis, first fell ill while he was a university student. His priority then was staying out of the hospital and completing his degree. The quickest way to do that was to take medication. But later, once his symptoms had stabilized, he added in talk therapy, which he says helped both with psychosis symptoms and with other problems such as depression.Some experts say that to identify the most effective treatment for each patient, clinicians may need to determine an illnesss underlying cause. At Tebartz van Elsts clinic in Freiburg, patients who come in after experiencing psychosis get a full workup, which often involves neuroimaging, blood tests and a lumbar puncture, to rule out any secondary cause for the symptoms. Such extensive tests are not the norm, however. In many parts of the world, including the U.S., whether a person will receive these types of tests depends largely on whether they end up in the office of a psychiatrist or a neurologist.Several large, ongoing efforts are aimed at trying to better characterize people with schizophrenia. The Psychiatric Biomarker Network, led by Steven E. Hyman of the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, was established in 2018 with the goal of finding biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid. The Accelerating Medicines Partnership Schizophrenia, launched in 2020 by several public and private institutions in the U.S. and the European Union, has a similar aim. Researchers hope to find markers that can identify people in the prodromal phase of schizophreniathe period before symptoms appear.Being able to identify people during this phase will open up the possibility of trying to develop preventive treatments, Howes says. His team has identified prodromal signs such as neuroimaging markers and early symptoms such as the Truman sign, where people feel a nagging sense that something strange is going onakin to the way the protagonist of the 1998 movie The Truman Show felt while unknowingly living on the set of a reality TV show. If you can prevent the illness to begin with, you can prevent all the disability and the chronic course that sometimes develops.Numerous questions remain open, such as to what extent the immune system is involved in schizophrenia and how neurotransmitters might be altered in different subgroups of people with the illnesses. Researchers have also identified other potentially important mechanisms that might underlie schizophrenia, such as abnormalities in metabolism. Preliminary research suggests that eating a ketogenic diet, which is high in fat and low in carbohydrates, might ease some of the symptoms of the disorder. Talk therapy is also emerging as helpful in treating people with schizophrenia. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy, which focuses on helping people adjust their ways of thinking and behaving, can reshape thought patterns that underlie psychosis or help patients deal with negative symptoms such as low motivation or a diminished ability to experience pleasure.Ultimately the hope is to provide better, more targeted therapies for people with schizophrenia. Some clinicians say the field of oncology has a blueprint for how to deal with such complex ailments. Cancer, which was once seen as a single disease, is now viewed as a collection of many diseases with different causes and mechanisms, all unified under a single name. In the same way that personalized therapies are becoming increasingly popular in oncology, researchers see this approach as the future for treating schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.Precision medicine is something that I think will emerge as a bigger and bigger part of the story of schizophrenia treatment, Krystal says. Eventually, he hopes, doctors will be able to tell patients, Youve got this biology, you need that treatment. That is where I think the future of understanding this biology of schizophrenia will take us.

0 Commenti

·0 condivisioni

·32 Views