0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

20 Visualizações

Diretório

Diretório

-

Faça Login para curtir, compartilhar e comentar!

-

TECHCRUNCH.COMThe TechCrunch Cyber GlossaryThe cybersecurity world is full of jargon and lingo. At TechCrunch, we have been writing about cybersecurity for years, and we frequently use technical terms and expressions to describe the nature of what is happening in the world. That’s why we have created this glossary, which includes some of the most common — and not so common — words and expressions that we use in our articles, and explanations of how, and why, we use them. This is a developing compendium, and we will update it regularly. If you have any feedback or suggestions for this glossary, get in touch. Advanced persistent threat (APT) An advanced persistent threat (APT) is often categorized as a hacker, or group of hackers, which gains and maintains unauthorized access to a targeted system. The main aim of an APT intruder is to remain undetected for long periods of time, often to conduct espionage and surveillance, to steal data, or sabotage critical systems. APTs are traditionally well-resourced hackers, including the funding to pay for their malicious campaigns, and access to hacking tools typically reserved by governments. As such, many of the long-running APT groups are associated with nation states, like China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. In recent years, we’ve seen examples of non-nation state cybercriminal groups that are financially motivated (such as theft and money laundering) carrying out cyberattacks similar in terms of persistence and capabilities as some traditional government-backed APT groups. (See: Hacker) Adversary-in-the-middle attack An adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) attack, traditionally known as a “man-in-the-middle” (MitM), is where someone intercepts network traffic at a particular point on the network in an attempt to eavesdrop or modify the data as it travels the internet. This is why encrypting data makes it more difficult for malicious actors to read or understand a person’s network traffic, which could contain personal information or secrets, like passwords. Adversary-in-the-middle attacks can be used legitimately by security researchers to help understand what data goes in and out of an app or web service, a process that can help identify security bugs and data exposures. Arbitrary code execution The ability to run commands or malicious code on an affected system, often because of a security vulnerability in the system’s software. Arbitrary code execution can be achieved either remotely or with physical access to an affected system (such as someone’s device). In the cases where arbitrary code execution can be achieved over the internet, security researchers typically call this remote code execution. Often, code execution is used as a way to plant a back door for maintaining long-term and persistent access to that system, or for running malware that can be used to access deeper parts of the system or other devices on the same network. (See also: Remote code execution) Attribution Attribution is the process of finding out and identifying who is behind a cyberattack. There is an often repeated mantra, “attribution is hard,” which is to warn cybersecurity professionals and the wider public that definitively establishing who was behind a cyberattack is no simple task. While it is not impossible to attribute, the answer is also dependent on the level of confidence in the assessment. Threat intelligence companies such as CrowdStrike, Kaspersky, and Mandiant, among others, have for years attributed cyberattacks and data breaches to groups or “clusters” of hackers, often referencing groups by a specific codename, based on a pattern of certain tactics, techniques and procedures as seen in previous attacks. Some threat intelligence firms go as far as publicly linking certain groups of hackers to specific governments or their intelligence agencies when the evidence points to it. Government agencies, however, have for years publicly accused other governments and countries of being behind cyberattacks, and have gone as far as identifying — and sometimes criminally charging — specific people working for those agencies. Backdoor A backdoor is a subjective term, but broadly refers to creating the means to gain future access to a system, device, or physical area. Backdoors can be found in software or hardware, such as a mechanism to gain access to a system (or space) in case of accidental lock-out, or for remotely providing technical support over the internet. Backdoors can have legitimate and helpful use cases, but backdoors can also be undocumented, maliciously planted, or otherwise unknown to the user or owner, which can weaken the security of the product and make it more susceptible to hacking or compromise. TechCrunch has a deeper dive on encryption backdoors. Black/white hat Hackers historically have been categorized as either “black hat” or “white hat,” usually depending on the motivations of the hacking activity carried out. A “black hat” hacker may be someone who might break the law and hack for money or personal gain, such as a cybercriminal. “White hat” hackers generally hack within legal bounds, like as part of a penetration test sanctioned by the target company, or to collect bug bounties finding flaws in various software and disclosing them to the affected vendor. For those who hack with less clearcut motivations, they may be regarded as a “gray hat.” Famously, the hacking group the L0pht used the term gray hat in an interview with The New York Times Magazine in 1999. While still commonly used in modern security parlance, many have moved away from the “hat” terminology. (Also see: Hacker, Hacktivist) Botnet Botnets are networks of hijacked internet-connected devices, such as webcams and home routers, that have been compromised by malware (or sometimes weak or default passwords) for the purposes of being used in cyberattacks. Botnets can be made up of hundreds or thousands of devices and are typically controlled by a command-and-control server that sends out commands to ensnared devices. Botnets can be used for a range of malicious reasons, like using the distributed network of devices to mask and shield the internet traffic of cybercriminals, deliver malware, or harness their collective bandwidth to maliciously crash websites and online services with huge amounts of junk internet traffic. (See also: Command-and-control server; Distributed denial-of-service) Brute force A brute-force attack is a common and rudimentary method of hacking into accounts or systems by automatically trying different combinations and permutations of letters and words to guess passwords. A less sophisticated brute-force attack is one that uses a “dictionary,” meaning a list of known and common passwords, for example. A well designed system should prevent these types of attacks by limiting the number of login attempts inside a specific timeframe, a solution called rate-limiting. Bug A bug is essentially the cause of a software glitch, such as an error or a problem that causes the software to crash or behave in an unexpected way. In some cases, a bug can also be a security vulnerability. The term “bug” originated in 1947, at a time when early computers were the size of rooms and made up of heavy mechanical and moving equipment. The first known incident of a bug found in a computer was when a moth disrupted the electronics of one of these room-sized computers. (See also: Vulnerability) Command-and-control (C2) server Command-and-control servers (also known as C2 servers) are used by cybercriminals to remotely manage and control their fleets of compromised devices and launch cyberattacks, such as delivering malware over the internet and launching distributed denial-of-service attacks. (See also: Botnet; Distributed denial-of-service) Crypto This is a word that can have two meanings depending on the context. Traditionally, in the context of computer science and cybersecurity, crypto is short for “cryptography,” the mathematical field of coding and decoding messages and data using encryption. Crypto has more recently also become short for cryptocurrency, such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the myriad blockchain-based decentralized digital currencies that have sprung up in the last fifteen years. As cryptocurrencies have grown from a niche community to a whole industry, crypto is now also used to refer to that whole industry and community. For years, the cryptography and cybersecurity community have wrestled with the adoption of this new meaning, going as far as making the phrases “crypto is not cryptocurrency” and “crypto means cryptography” into something that features on its own dedicated website and even T-shirts. Languages change over time depending on how people use words. As such, TechCrunch accepts the reality where crypto has different meanings depending on context, and where the context isn’t clear, then we spell out cryptography, or cryptocurrency. Cryptojacking Cryptojacking is when a device’s computational power is used, with or without the owner’s permission, to generate cryptocurrency. Developers sometimes bundle code in apps and on websites, which then uses the device’s processors to complete complex mathematical calculations needed to create new cryptocurrency. The generated cryptocurrency is then deposited in virtual wallets owned by the developer. Some malicious hackers use malware to deliberately compromise large numbers of unwitting computers to generate cryptocurrency on a large and distributed scale. Dark and deep web The world wide web is the public content that flows across the pipes of the internet, much of what is online today is for anyone to access at any time. The “deep web,” however, is the content that is kept behind paywalls and member-only spaces, or any part of the web that is not readily accessible or browsable with a search engine. Then there is the “dark web,” which is the part of the internet that allows users to remain anonymous but requires certain software (such as the Tor Browser) to access, depending on the part of the dark web you’re trying to access. Anonymity benefits those who live and work in highly censored or surveilled countries, but it also can benefit criminals. There is nothing inherently criminal or nefarious about accessing the dark web; many popular websites also offer dark web versions so that users around the world can access their content. TechCrunch has a more detailed explainer on what the dark web is. Data breach When we talk about data breaches, we ultimately mean the improper removal of data from where it should have been. But the circumstances matter and can alter the terminology we use to describe a particular incident. A data breach is when protected data was confirmed to have improperly left a system from where it was originally stored and usually confirmed when someone discovers the compromised data. More often than not, we’re referring to the exfiltration of data by a malicious cyberattacker or otherwise detected as a result of an inadvertent exposure. Depending on what is known about the incident, we may describe it in more specific terms where details are known. (See also: Data exposure; Data leak) Data exposure A data exposure (a type of data breach) is when protected data is stored on a system that has no access controls, such as because of human error or a misconfiguration. This might include cases where a system or database is connected to the internet but without a password. Just because data was exposed doesn’t mean the data was actively discovered, but nevertheless could still be considered a data breach. Data leak A data leak (a type of data breach) is where protected data is stored on a system in a way that it was allowed to escape, such as due to a previously unknown vulnerability in the system or by way of insider access (such as an employee). A data leak can mean that data could have been exfiltrated or otherwise collected, but there may not always be the technical means, such as logs, to know for sure. Deepfake Deepfakes are AI-generated videos, audios, or pictures designed to look real, often with the goal of fooling people into thinking they are genuine. Deepfakes are developed with a specific type of machine learning known as deep learning, hence its name. Examples of deepfakes can range from relatively harmless, like a video of a celebrity saying something funny or outrageous, to more harmful efforts. In recent years, there have been documented cases of deepfaked political content designed to discredit politicians and influence voters, while other malicious deepfakes have relied on using recordings of executives designed to trick company employees into giving up sensitive information or sending money to scammers. Deepfakes are also contributing to the proliferation of nonconsensual sexual images. Def Con (aka DEFCON) Def Con is one of the most important hacking conferences in the world, held annually in Las Vegas, usually during August. Launched in 1993 as a party for some hacker friends, it has now become an annual gathering of almost 30,000 hackers and cybersecurity professionals, with dozens of talks, capture-the-flag hacking competitions, and themed “villages,” where attendees can learn how to hack internet-connected devices, voting systems, and even aircraft. Unlike other conferences like RSA or Black Hat, Def Con is decidedly not a business conference, and the focus is much more on hacker culture. There is a vendor area, but it usually includes nonprofits like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, The Calyx Institute, and the Tor Project, as well as relatively small cybersecurity companies. Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) A distributed denial-of-service, or DDoS, is a kind of cyberattack that involves flooding targets on the internet with junk web traffic in order to overload and crash the servers and cause the service, such as a website, online store, or gaming platform to go down. DDoS attacks are launched by botnets, which are made up of networks of hacked internet-connected devices (such as home routers and webcams) that can be remotely controlled by a malicious operator, usually from a command-and-control server. Botnets can be made up of hundreds or thousands of hijacked devices. While a DDoS is a form of cyberattack, these data-flooding attacks are not “hacks” in themselves, as they don’t involve the breach and exfiltration of data from their targets, but instead cause a “denial of service” event to the affected service. (See also: Botnet; Command-and-control server) Encryption Encryption is the way and means in which information, such as files, documents, and private messages, are scrambled to make the data unreadable to anyone other than to its intended owner or recipient. Encrypted data is typically scrambled using an encryption algorithm — essentially a set of mathematical formulas that determines how Nearly all modern encryption algorithms in use today are open source, allowing anyone (including security professionals and cryptographers) to review and check the algorithm to make sure it’s free of faults or flaws. Some encryption algorithms are stronger than others, meaning data protected by some weaker algorithms can be decrypted by harnessing large amounts of computational power. Encryption is different from encoding, which simply converts data into a different and standardized format, usually for the benefit of allowing computers to read the data. (See also: End-to-end encryption) End-to-end encryption (E2EE) End-to-end encryption (or E2EE) is a security feature built into many messaging and file-sharing apps, and is widely considered one of the strongest ways of securing digital communications as they traverse the internet. E2EE scrambles the file or message on the sender’s device before it’s sent in a way that allows only the intended recipient to decrypt its contents, making it near-impossible for anyone — including a malicious hacker, or even the app maker — to snoop inside on someone’s private communications. In recent years, E2EE has become the default security standard for many messaging apps, including Apple’s iMessage, Facebook Messenger, Signal, and WhatsApp. E2EE has also become the subject of governmental frustration in recent years, as encryption makes it impossible for tech companies or app providers to give over information that they themselves do not have access to. (See also: Encryption) Escalation of privileges Most modern systems are protected with multiple layers of security, including the ability to set user accounts with more restricted access to the underlying system’s configurations and settings. This prevents these users — or anyone with improper access to one of these user accounts — from tampering with the core underlying system. However, an “escalation of privileges” event can involve exploiting a bug or tricking the system into granting the user more access rights than they should have. Malware can also take advantage of bugs or flaws caused by escalation of privileges by gaining deeper access to a device or a connected network, potentially allowing the malware to spread. Espionage When we talk about espionage, we’re generally referring to threat groups or hacking campaigns that are dedicated to spying, and are typically characterized by their stealth. Espionage-related hacks are usually aimed at gaining and maintaining stealthy persistent access to a target’s network to carry out passive surveillance, reconnaissance for future cyberattacks, or the long-term collection and exfiltration of data. Espionage operations are often carried out by governments and intelligence agencies, though not exclusively. Exploit An exploit is the way and means in which a vulnerability is abused or taken advantage of, usually in order to break into a system. (See also: Bug; Vulnerability) Extortion In general terms, extortion is the act of obtaining something, usually money, through the use of force and intimidation. Cyber extortion is no different, as it typically refers to a category of cybercrime whereby attackers demand payment from victims by threatening to damage, disrupt, or expose their sensitive information. Extortion is often used in ransomware attacks, where hackers typically exfiltrate company data before demanding a ransom payment from the hacked victim. But extortion has quickly become its own category of cybercrime, with many, often younger, financially motivated hackers, opting to carry out extortion-only attacks, which snub the use of encryption in favor of simple data theft. (Also see: Ransomware) Forensics Forensic investigations involve analyzing data and information contained in a computer, server, or mobile device, looking for evidence of a hack, crime, or some sort of malfeasance. Sometimes, in order to access the data, corporate or law enforcement investigators rely on specialized devices and tools, like those made by Cellebrite and Grayshift, which are designed to unlock and break the security of computers and cellphones to access the data within. Hacker There is no one single definition of “hacker.” The term has its own rich history, culture, and meaning within the security community. Some incorrectly conflate hackers, or hacking, with wrongdoing. By our definition and use, we broadly refer to a “hacker” as someone who is a “breaker of things,” usually by altering how something works to make it perform differently in order to meet their objectives. In practice, that can be something as simple as repairing a machine with non-official parts to make it function differently as intended, or work even better. In the cybersecurity sense, a hacker is typically someone who breaks a system or breaks the security of a system. That could be anything from an internet-connected computer system to a simple door lock. But the person’s intentions and motivations (if known) matter in our reporting, and guides how we accurately describe the person, or their activity. There are ethical and legal differences between a hacker who works as a security researcher, who is professionally tasked with breaking into a company’s systems with their permission to identify security weaknesses that can be fixed before a malicious individual has a chance to exploit them; and a malicious hacker who gains unauthorized access to a system and steals data without obtaining anyone’s permission. Because the term “hacker” is inherently neutral, we generally apply descriptors in our reporting to provide context about who we’re talking about. If we know that an individual works for a government and is contracted to maliciously steal data from a rival government, we’re likely to describe them as a nation-state or government hackeradvanced persistent threat), for example. If a gang is known to use malware to steal funds from individuals’ bank accounts, we may describe them as financially motivated hackers, or if there is evidence of criminality or illegality (such as an indictment), we may describe them simply as cybercriminals. And, if we don’t know motivations or intentions, or a person describes themselves as such, we may simply refer to a subject neutrally as a “hacker,” where appropriate. Hack-and-leak operation Sometimes, hacking and stealing data is only the first step. In some cases, hackers then leak the stolen data to journalists, or directly post the data online for anyone to see. The goal can be either to embarrass the hacking victim, or to expose alleged malfeasance. The origins of modern hack-and-leak operations date back to the early- and mid-2000s, when groups like el8, pHC (“Phrack High Council”) and zf0 were targeting people in the cybersecurity industry who, according to these groups, had foregone the hacker ethos and had sold out. Later, there are the examples of hackers associated with Anonymous and leaking data from U.S. government contractor HBGary, and North Korean hackers leaking emails stolen from Sony as retribution for the Hollywood comedy, The Interview. Some of the most recent and famous examples are the hack against the now-defunct government spyware pioneer Hacking Team in 2015, and the infamous Russian government-led hack-and-leak of Democratic National Committee emails ahead of the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Iranian government hackers tried to emulate the 2016 playbook during the 2024 elections. Hacktivist A particular kind of hacker who hacks for what they — and perhaps the public — perceive as a good cause, hence the portmanteau of the words “hacker” and “activist.” Hacktivism has been around for more than two decades, starting perhaps with groups like the Cult of the Dead Cow in the late 1990s. Since then, there have been several high profile examples of hacktivist hackers and groups, such as Anonymous, LulzSec, and Phineas Fisher. (Also see: Hacker) Infosec Short for “information security,” an alternative term used to describe defensive cybersecurity focused on the protection of data and information. “Infosec” may be the preferred term for industry veterans, while the term “cybersecurity” has become widely accepted. In modern times, the two terms have become largely interchangeable. Infostealers Infostealers are malware capable of stealing information from a person’s computer or device. Infostealers are often bundled in pirated software, like Redline, which when installed will primarily seek out passwords and other credentials stored in the person’s browser or password manager, then surreptitiously upload the victim’s passwords to the attacker’s systems. This lets the attacker sign in using those stolen passwords. Some infostealers are also capable of stealing session tokens from a user’s browser, which allow the attacker to sign in to a person’s online account as if they were that user but without needing their password or multi-factor authentication code. (See also: Malware) Jailbreak Jailbreaking is used in several contexts to mean the use of exploits and other hacking techniques to circumvent the security of a device, or removing the restrictions a manufacturer puts on hardware or software. In the context of iPhones, for example, a jailbreak is a technique to remove Apple’s restrictions on installing apps outside of its “walled garden” or to gain the ability to conduct security research on Apple devices, which is normally highly restricted. In the context of AI, jailbreaking means figuring out a way to get a chatbot to give out information that it’s not supposed to. Kernel The kernel, as its name suggests, is the core part of an operating system that connects and controls virtually all hardware and software. As such, the kernel has the highest level of privileges, meaning it has access to virtually any data on the device. That’s why, for example, apps such as antivirus and anti-cheat software run at the kernel level, as they require broad access to the device. Having kernel access allows these apps to monitor for malicious code. Malware Malware is a broad umbrella term that describes malicious software. Malware can land in many forms and be used to exploit systems in different ways. As such, malware that is used for specific purposes can often be referred to as its own subcategory. For example, the type of malware used for conducting surveillance on people’s devices is also called “spyware,” while malware that encrypts files and demands money from its victims is called “ransomware.” (See also: Infostealers; Ransomware; Spyware) Metadata is information about something digital, rather than its contents. That can include details about the size of a file or document, who created it, and when, or in the case of digital photos, where the image was taken and information about the device that took the photo. Metadata may not identify the contents of a file, but it can be useful in determining where a document came from or who authored it. Metadata can also refer to information about an exchange, such as who made a call or sent a text message, but not the contents of the call or the message. Multi-factor authentication Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is the common umbrella term for describing when a person must provide a second piece of information, aside from a username and password, to log into a system. MFA (or two-factor; also known as 2FA) can prevent malicious hackers from re-using a person’s stolen credentials by requiring a time-sensitive code sent to or generated from a registered device owned by the account holder, or the use of a physical token or key. Operational security (OPSEC) Operational security, or OPSEC for short, is the practice of keeping information secret in various situations. Practicing OPSEC means thinking about what information you are trying to protect, from whom, and how you’re going to protect it. OPSEC is less about what tools you are using, and more about how you are using them and for what purpose. For example, government officials discussing plans to bomb foreign countries on Signal are practicing bad OPSEC because the app is not designed for that use-case, and runs on devices that are more vulnerable to hackers than highly restricted systems specifically designed for military communications. On the other hand, journalists using Signal to talk to sensitive sources is generally good OPSEC because it makes it harder for those communications to be intercepted by eavesdroppers. (See also: Threat model) Penetration testing Also known as “pen-testing,” this is the process where security researchers “stress-test” the security of a product, network, or system, usually by attempting to modify the way that the product typically operates. Software makers may ask for a pen-test on a product, or of their internal network, to ensure that they are free from serious or critical security vulnerabilities, though a pen-test does not guarantee that a product will be completely bug-free. Phishing Phishing is a type of cyberattack where hackers trick their targets into clicking or tapping on a malicious link, or opening a malicious attachment. The term derives from “fishing,” because hackers often use “lures” to convincingly trick their targets in these types of attacks. A phishing lure could be attachment coming from an email address that appears to be legitimate, or even an email spoofing the email address of a person that the target really knows. Sometimes, the lure could be something that might appear to be important to the target, like sending a forged document to a journalist that appears to show corruption, or a fake conference invite for human rights defenders. There is an often cited adage by the well-known cybersecurity influencer The Grugq, which encapsulates the value of phishing: “Give a man an 0day and he’ll have access for a day, teach a man to phish and he’ll have access for life.” (Also see: Social engineering) Ransomware Ransomware is a type of malicious software (or malware) that prevents device owners from accessing its data, typically by encrypting the person’s files. Ransomware is usually deployed by cybercriminal gangs who demand a ransom payment — usually cryptocurrency — in return for providing the private key to decrypt the person’s data. In some cases, ransomware gangs will steal the victim’s data before encrypting it, allowing the criminals to extort the victim further by threatening to publish the files online. Paying a ransomware gang is no guarantee that the victim will get their stolen data back, or that the gang will delete the stolen data. One of the first-ever ransomware attacks was documented in 1989, in which malware was distributed via floppy disk (an early form of removable storage) to attendees of the World Health Organization’s AIDS conference. Since then, ransomware has evolved into a multibillion-dollar criminal industry as attackers refine their tactics and hone in on big-name corporate victims. (See also: Malware; Sanctions) Remote code execution Remote code execution refers to the ability to run commands or malicious code (such as malware) on a system from over a network, often the internet, without requiring any human interaction from the target. Remote code execution attacks can range in complexity but can be highly damaging when vulnerabilities are exploited. (See also: Arbitrary code execution) Sanctions Cybersecurity-related sanctions work similarly to traditional sanctions in that they make it illegal for businesses or individuals to transact with a sanctioned entity. In the case of cyber sanctions, these entities are suspected of carrying out malicious cyber-enabled activities, such as ransomware attacks or the laundering of ransom payments made to hackers. The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) administers sanctions. The Treasury’s Cyber-Related Sanctions Program was established in 2015 as part of the Obama administration’s response to cyberattacks targeting U.S. government agencies and private sector U.S. entities. While a relatively new addition to the U.S. government’s bureaucratic armory against ransomware groups, sanctions are increasingly used to hamper and deter malicious state actors from conducting cyberattacks. Sanctions are often used against hackers who are out of reach of U.S. indictments or arrest warrants, such as ransomware crews based in Russia. Sandbox A sandbox is a part of a system that is isolated from the rest. The goal is to create a protected environment where a hacker can compromise the sandbox, but without allowing further access to the rest of the system. For example, mobile applications usually run in their own sandboxes. If hackers compromise a browser, for example, they cannot immediately compromise the operating system or another app on the same device. Security researchers also use sandboxes in both physical and virtual environments (such as a virtual machine) to analyze malicious code without risking compromising their own computers or networks. SIM swap SIM swapping is a type of attack where hackers hijack and take control of a person’s phone number, often with the goal of then using the phone number to log into the target’s sensitive accounts, such as their email address, bank account, or cryptocurrency wallet. This attack exploits the way that online accounts sometimes rely on a phone number as a fallback in the event of losing a password. SIM swaps often rely on hackers using social engineering techniques to trick phone carrier employees (or bribing them) into handing over control of a person’s account, as well as hacking into carrier systems. Social engineering is the art of human deception, and encompasses several techniques a hacker can use to deceive their target into doing something they normally would not do. Phishing, for example, can be classified as a type of social engineering attack because hackers trick targets into clicking on a malicious link or opening a malicious attachment, or calling someone on the phone while pretending to be their employer’s IT department. Social engineering can also be used in the real world, for example, to convince building security employees to let someone who shouldn’t be allowed to enter the building. Some call it “human hacking” because social engineering attacks don’t necessarily have to involve technology. (Also see: Phishing) Spyware (commercial, government) A broad term, like malware, that covers a range of surveillance monitoring software. Spyware is typically used to refer to malware made by private companies, such as NSO Group’s Pegasus, Intellexa’s Predator, and Hacking Team’s Remote Control System, among others, which the companies sell to government agencies. In more generic terms, these types of malware are like remote access tools, which allows their operators — usually government agents — to spy and monitor their targets, giving them the ability to access a device’s camera and microphone or exfiltrate data. Spyware is also referred to as commercial or government spyware, or mercenary spyware. (See also: Stalkerware) Stalkerware Stalkerware is a kind of surveillance malware (and a form of spyware) that is usually sold to ordinary consumers under the guise of child or employee monitoring software but is often used for the purposes of spying on the phones of unwitting individuals, oftentimes spouses and domestic partners. The spyware grants access to the target’s messages, location, and more. Stalkerware typically requires physical access to a target’s device, which gives the attacker the ability to install it directly on the target’s device, often because the attacker knows the target’s passcode. (See also: Spyware) Threat model What are you trying to protect? Who are you worried about that could go after you or your data? How could these attackers get to the data? The answers to these kinds of questions are what will lead you to create a threat model. In other words, threat modeling is a process that an organization or an individual has to go through to design software that is secure, and devise techniques to secure it. A threat model can be focused and specific depending on the situation. A human rights activist in an authoritarian country has a different set of adversaries, and data, to protect than a large corporation in a democratic country that is worried about ransomware, for example. (See also: Operational security) When we describe “unauthorized” access, we’re referring to the accessing of a computer system by breaking any of its security features, such as a login prompt or a password, which would be considered illegal under the U.S. Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, or the CFAA. The Supreme Court in 2021 clarified the CFAA, finding that accessing a system lacking any means of authorization — for example, a database with no password — is not illegal, as you cannot break a security feature that isn’t there. It’s worth noting that “unauthorized” is a broadly used term and often used by companies subjectively, and as such has been used to describe malicious hackers who steal someone’s password to break in through to incidents of insider access or abuse by employees. Virtual private network (VPN) A virtual private network, or VPN, is a networking technology that allows someone to “virtually” access a private network, such as their workplace or home, from anywhere else in the world. Many use a VPN provider to browse the web, thinking that this can help to avoid online surveillance. TechCrunch has a skeptics’ guide to VPNs that can help you decide if a VPN makes sense for you. If it does, we’ll show you how to set up your own private and encrypted VPN server that only you control. And if it doesn’t, we explore some of the privacy tools and other measures you can take to meaningfully improve your privacy online. Vulnerability A vulnerability (also referred to as a security flaw) is a type of bug that causes software to crash or behave in an unexpected way that affects the security of the system or its data. Sometimes, two or more vulnerabilities can be used in conjunction with each other — known as “vulnerability chaining” — to gain deeper access to a targeted system. (See also: Bug; Exploit) Zero-click (and one-click) attacks Malicious attacks can sometimes be categorized and described by the amount of user interaction that malware, or a malicious hacker, needs in order to achieve successful compromise. One-click attacks refer to the target having to interact only once with the incoming lure, such as clicking on a malicious link or opening an attachment, to grant the intruder access. But zero-click attacks differ in that they can achieve compromise without the target having to click or tap anything. Zero-clicks are near-invisible to the target and are far more difficult to identify. As such, zero-click attacks are almost always delivered over the internet, and are often reserved for high-value targets for their stealthy capabilities, such as deploying spyware. (Also see: Spyware) Zero-day A zero-day is a specific type of security vulnerability that has been publicly disclosed or exploited but the vendor who makes the affected hardware or software has not been given time (or “zero days”) to fix the problem. As such, there may be no immediate fix or mitigation to prevent an affected system from being compromised. This can be particularly problematic for internet-connected devices. (See also: Vulnerability) First published on September 20, 2024.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 28 Visualizações

TECHCRUNCH.COMThe TechCrunch Cyber GlossaryThe cybersecurity world is full of jargon and lingo. At TechCrunch, we have been writing about cybersecurity for years, and we frequently use technical terms and expressions to describe the nature of what is happening in the world. That’s why we have created this glossary, which includes some of the most common — and not so common — words and expressions that we use in our articles, and explanations of how, and why, we use them. This is a developing compendium, and we will update it regularly. If you have any feedback or suggestions for this glossary, get in touch. Advanced persistent threat (APT) An advanced persistent threat (APT) is often categorized as a hacker, or group of hackers, which gains and maintains unauthorized access to a targeted system. The main aim of an APT intruder is to remain undetected for long periods of time, often to conduct espionage and surveillance, to steal data, or sabotage critical systems. APTs are traditionally well-resourced hackers, including the funding to pay for their malicious campaigns, and access to hacking tools typically reserved by governments. As such, many of the long-running APT groups are associated with nation states, like China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. In recent years, we’ve seen examples of non-nation state cybercriminal groups that are financially motivated (such as theft and money laundering) carrying out cyberattacks similar in terms of persistence and capabilities as some traditional government-backed APT groups. (See: Hacker) Adversary-in-the-middle attack An adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) attack, traditionally known as a “man-in-the-middle” (MitM), is where someone intercepts network traffic at a particular point on the network in an attempt to eavesdrop or modify the data as it travels the internet. This is why encrypting data makes it more difficult for malicious actors to read or understand a person’s network traffic, which could contain personal information or secrets, like passwords. Adversary-in-the-middle attacks can be used legitimately by security researchers to help understand what data goes in and out of an app or web service, a process that can help identify security bugs and data exposures. Arbitrary code execution The ability to run commands or malicious code on an affected system, often because of a security vulnerability in the system’s software. Arbitrary code execution can be achieved either remotely or with physical access to an affected system (such as someone’s device). In the cases where arbitrary code execution can be achieved over the internet, security researchers typically call this remote code execution. Often, code execution is used as a way to plant a back door for maintaining long-term and persistent access to that system, or for running malware that can be used to access deeper parts of the system or other devices on the same network. (See also: Remote code execution) Attribution Attribution is the process of finding out and identifying who is behind a cyberattack. There is an often repeated mantra, “attribution is hard,” which is to warn cybersecurity professionals and the wider public that definitively establishing who was behind a cyberattack is no simple task. While it is not impossible to attribute, the answer is also dependent on the level of confidence in the assessment. Threat intelligence companies such as CrowdStrike, Kaspersky, and Mandiant, among others, have for years attributed cyberattacks and data breaches to groups or “clusters” of hackers, often referencing groups by a specific codename, based on a pattern of certain tactics, techniques and procedures as seen in previous attacks. Some threat intelligence firms go as far as publicly linking certain groups of hackers to specific governments or their intelligence agencies when the evidence points to it. Government agencies, however, have for years publicly accused other governments and countries of being behind cyberattacks, and have gone as far as identifying — and sometimes criminally charging — specific people working for those agencies. Backdoor A backdoor is a subjective term, but broadly refers to creating the means to gain future access to a system, device, or physical area. Backdoors can be found in software or hardware, such as a mechanism to gain access to a system (or space) in case of accidental lock-out, or for remotely providing technical support over the internet. Backdoors can have legitimate and helpful use cases, but backdoors can also be undocumented, maliciously planted, or otherwise unknown to the user or owner, which can weaken the security of the product and make it more susceptible to hacking or compromise. TechCrunch has a deeper dive on encryption backdoors. Black/white hat Hackers historically have been categorized as either “black hat” or “white hat,” usually depending on the motivations of the hacking activity carried out. A “black hat” hacker may be someone who might break the law and hack for money or personal gain, such as a cybercriminal. “White hat” hackers generally hack within legal bounds, like as part of a penetration test sanctioned by the target company, or to collect bug bounties finding flaws in various software and disclosing them to the affected vendor. For those who hack with less clearcut motivations, they may be regarded as a “gray hat.” Famously, the hacking group the L0pht used the term gray hat in an interview with The New York Times Magazine in 1999. While still commonly used in modern security parlance, many have moved away from the “hat” terminology. (Also see: Hacker, Hacktivist) Botnet Botnets are networks of hijacked internet-connected devices, such as webcams and home routers, that have been compromised by malware (or sometimes weak or default passwords) for the purposes of being used in cyberattacks. Botnets can be made up of hundreds or thousands of devices and are typically controlled by a command-and-control server that sends out commands to ensnared devices. Botnets can be used for a range of malicious reasons, like using the distributed network of devices to mask and shield the internet traffic of cybercriminals, deliver malware, or harness their collective bandwidth to maliciously crash websites and online services with huge amounts of junk internet traffic. (See also: Command-and-control server; Distributed denial-of-service) Brute force A brute-force attack is a common and rudimentary method of hacking into accounts or systems by automatically trying different combinations and permutations of letters and words to guess passwords. A less sophisticated brute-force attack is one that uses a “dictionary,” meaning a list of known and common passwords, for example. A well designed system should prevent these types of attacks by limiting the number of login attempts inside a specific timeframe, a solution called rate-limiting. Bug A bug is essentially the cause of a software glitch, such as an error or a problem that causes the software to crash or behave in an unexpected way. In some cases, a bug can also be a security vulnerability. The term “bug” originated in 1947, at a time when early computers were the size of rooms and made up of heavy mechanical and moving equipment. The first known incident of a bug found in a computer was when a moth disrupted the electronics of one of these room-sized computers. (See also: Vulnerability) Command-and-control (C2) server Command-and-control servers (also known as C2 servers) are used by cybercriminals to remotely manage and control their fleets of compromised devices and launch cyberattacks, such as delivering malware over the internet and launching distributed denial-of-service attacks. (See also: Botnet; Distributed denial-of-service) Crypto This is a word that can have two meanings depending on the context. Traditionally, in the context of computer science and cybersecurity, crypto is short for “cryptography,” the mathematical field of coding and decoding messages and data using encryption. Crypto has more recently also become short for cryptocurrency, such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the myriad blockchain-based decentralized digital currencies that have sprung up in the last fifteen years. As cryptocurrencies have grown from a niche community to a whole industry, crypto is now also used to refer to that whole industry and community. For years, the cryptography and cybersecurity community have wrestled with the adoption of this new meaning, going as far as making the phrases “crypto is not cryptocurrency” and “crypto means cryptography” into something that features on its own dedicated website and even T-shirts. Languages change over time depending on how people use words. As such, TechCrunch accepts the reality where crypto has different meanings depending on context, and where the context isn’t clear, then we spell out cryptography, or cryptocurrency. Cryptojacking Cryptojacking is when a device’s computational power is used, with or without the owner’s permission, to generate cryptocurrency. Developers sometimes bundle code in apps and on websites, which then uses the device’s processors to complete complex mathematical calculations needed to create new cryptocurrency. The generated cryptocurrency is then deposited in virtual wallets owned by the developer. Some malicious hackers use malware to deliberately compromise large numbers of unwitting computers to generate cryptocurrency on a large and distributed scale. Dark and deep web The world wide web is the public content that flows across the pipes of the internet, much of what is online today is for anyone to access at any time. The “deep web,” however, is the content that is kept behind paywalls and member-only spaces, or any part of the web that is not readily accessible or browsable with a search engine. Then there is the “dark web,” which is the part of the internet that allows users to remain anonymous but requires certain software (such as the Tor Browser) to access, depending on the part of the dark web you’re trying to access. Anonymity benefits those who live and work in highly censored or surveilled countries, but it also can benefit criminals. There is nothing inherently criminal or nefarious about accessing the dark web; many popular websites also offer dark web versions so that users around the world can access their content. TechCrunch has a more detailed explainer on what the dark web is. Data breach When we talk about data breaches, we ultimately mean the improper removal of data from where it should have been. But the circumstances matter and can alter the terminology we use to describe a particular incident. A data breach is when protected data was confirmed to have improperly left a system from where it was originally stored and usually confirmed when someone discovers the compromised data. More often than not, we’re referring to the exfiltration of data by a malicious cyberattacker or otherwise detected as a result of an inadvertent exposure. Depending on what is known about the incident, we may describe it in more specific terms where details are known. (See also: Data exposure; Data leak) Data exposure A data exposure (a type of data breach) is when protected data is stored on a system that has no access controls, such as because of human error or a misconfiguration. This might include cases where a system or database is connected to the internet but without a password. Just because data was exposed doesn’t mean the data was actively discovered, but nevertheless could still be considered a data breach. Data leak A data leak (a type of data breach) is where protected data is stored on a system in a way that it was allowed to escape, such as due to a previously unknown vulnerability in the system or by way of insider access (such as an employee). A data leak can mean that data could have been exfiltrated or otherwise collected, but there may not always be the technical means, such as logs, to know for sure. Deepfake Deepfakes are AI-generated videos, audios, or pictures designed to look real, often with the goal of fooling people into thinking they are genuine. Deepfakes are developed with a specific type of machine learning known as deep learning, hence its name. Examples of deepfakes can range from relatively harmless, like a video of a celebrity saying something funny or outrageous, to more harmful efforts. In recent years, there have been documented cases of deepfaked political content designed to discredit politicians and influence voters, while other malicious deepfakes have relied on using recordings of executives designed to trick company employees into giving up sensitive information or sending money to scammers. Deepfakes are also contributing to the proliferation of nonconsensual sexual images. Def Con (aka DEFCON) Def Con is one of the most important hacking conferences in the world, held annually in Las Vegas, usually during August. Launched in 1993 as a party for some hacker friends, it has now become an annual gathering of almost 30,000 hackers and cybersecurity professionals, with dozens of talks, capture-the-flag hacking competitions, and themed “villages,” where attendees can learn how to hack internet-connected devices, voting systems, and even aircraft. Unlike other conferences like RSA or Black Hat, Def Con is decidedly not a business conference, and the focus is much more on hacker culture. There is a vendor area, but it usually includes nonprofits like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, The Calyx Institute, and the Tor Project, as well as relatively small cybersecurity companies. Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) A distributed denial-of-service, or DDoS, is a kind of cyberattack that involves flooding targets on the internet with junk web traffic in order to overload and crash the servers and cause the service, such as a website, online store, or gaming platform to go down. DDoS attacks are launched by botnets, which are made up of networks of hacked internet-connected devices (such as home routers and webcams) that can be remotely controlled by a malicious operator, usually from a command-and-control server. Botnets can be made up of hundreds or thousands of hijacked devices. While a DDoS is a form of cyberattack, these data-flooding attacks are not “hacks” in themselves, as they don’t involve the breach and exfiltration of data from their targets, but instead cause a “denial of service” event to the affected service. (See also: Botnet; Command-and-control server) Encryption Encryption is the way and means in which information, such as files, documents, and private messages, are scrambled to make the data unreadable to anyone other than to its intended owner or recipient. Encrypted data is typically scrambled using an encryption algorithm — essentially a set of mathematical formulas that determines how Nearly all modern encryption algorithms in use today are open source, allowing anyone (including security professionals and cryptographers) to review and check the algorithm to make sure it’s free of faults or flaws. Some encryption algorithms are stronger than others, meaning data protected by some weaker algorithms can be decrypted by harnessing large amounts of computational power. Encryption is different from encoding, which simply converts data into a different and standardized format, usually for the benefit of allowing computers to read the data. (See also: End-to-end encryption) End-to-end encryption (E2EE) End-to-end encryption (or E2EE) is a security feature built into many messaging and file-sharing apps, and is widely considered one of the strongest ways of securing digital communications as they traverse the internet. E2EE scrambles the file or message on the sender’s device before it’s sent in a way that allows only the intended recipient to decrypt its contents, making it near-impossible for anyone — including a malicious hacker, or even the app maker — to snoop inside on someone’s private communications. In recent years, E2EE has become the default security standard for many messaging apps, including Apple’s iMessage, Facebook Messenger, Signal, and WhatsApp. E2EE has also become the subject of governmental frustration in recent years, as encryption makes it impossible for tech companies or app providers to give over information that they themselves do not have access to. (See also: Encryption) Escalation of privileges Most modern systems are protected with multiple layers of security, including the ability to set user accounts with more restricted access to the underlying system’s configurations and settings. This prevents these users — or anyone with improper access to one of these user accounts — from tampering with the core underlying system. However, an “escalation of privileges” event can involve exploiting a bug or tricking the system into granting the user more access rights than they should have. Malware can also take advantage of bugs or flaws caused by escalation of privileges by gaining deeper access to a device or a connected network, potentially allowing the malware to spread. Espionage When we talk about espionage, we’re generally referring to threat groups or hacking campaigns that are dedicated to spying, and are typically characterized by their stealth. Espionage-related hacks are usually aimed at gaining and maintaining stealthy persistent access to a target’s network to carry out passive surveillance, reconnaissance for future cyberattacks, or the long-term collection and exfiltration of data. Espionage operations are often carried out by governments and intelligence agencies, though not exclusively. Exploit An exploit is the way and means in which a vulnerability is abused or taken advantage of, usually in order to break into a system. (See also: Bug; Vulnerability) Extortion In general terms, extortion is the act of obtaining something, usually money, through the use of force and intimidation. Cyber extortion is no different, as it typically refers to a category of cybercrime whereby attackers demand payment from victims by threatening to damage, disrupt, or expose their sensitive information. Extortion is often used in ransomware attacks, where hackers typically exfiltrate company data before demanding a ransom payment from the hacked victim. But extortion has quickly become its own category of cybercrime, with many, often younger, financially motivated hackers, opting to carry out extortion-only attacks, which snub the use of encryption in favor of simple data theft. (Also see: Ransomware) Forensics Forensic investigations involve analyzing data and information contained in a computer, server, or mobile device, looking for evidence of a hack, crime, or some sort of malfeasance. Sometimes, in order to access the data, corporate or law enforcement investigators rely on specialized devices and tools, like those made by Cellebrite and Grayshift, which are designed to unlock and break the security of computers and cellphones to access the data within. Hacker There is no one single definition of “hacker.” The term has its own rich history, culture, and meaning within the security community. Some incorrectly conflate hackers, or hacking, with wrongdoing. By our definition and use, we broadly refer to a “hacker” as someone who is a “breaker of things,” usually by altering how something works to make it perform differently in order to meet their objectives. In practice, that can be something as simple as repairing a machine with non-official parts to make it function differently as intended, or work even better. In the cybersecurity sense, a hacker is typically someone who breaks a system or breaks the security of a system. That could be anything from an internet-connected computer system to a simple door lock. But the person’s intentions and motivations (if known) matter in our reporting, and guides how we accurately describe the person, or their activity. There are ethical and legal differences between a hacker who works as a security researcher, who is professionally tasked with breaking into a company’s systems with their permission to identify security weaknesses that can be fixed before a malicious individual has a chance to exploit them; and a malicious hacker who gains unauthorized access to a system and steals data without obtaining anyone’s permission. Because the term “hacker” is inherently neutral, we generally apply descriptors in our reporting to provide context about who we’re talking about. If we know that an individual works for a government and is contracted to maliciously steal data from a rival government, we’re likely to describe them as a nation-state or government hackeradvanced persistent threat), for example. If a gang is known to use malware to steal funds from individuals’ bank accounts, we may describe them as financially motivated hackers, or if there is evidence of criminality or illegality (such as an indictment), we may describe them simply as cybercriminals. And, if we don’t know motivations or intentions, or a person describes themselves as such, we may simply refer to a subject neutrally as a “hacker,” where appropriate. Hack-and-leak operation Sometimes, hacking and stealing data is only the first step. In some cases, hackers then leak the stolen data to journalists, or directly post the data online for anyone to see. The goal can be either to embarrass the hacking victim, or to expose alleged malfeasance. The origins of modern hack-and-leak operations date back to the early- and mid-2000s, when groups like el8, pHC (“Phrack High Council”) and zf0 were targeting people in the cybersecurity industry who, according to these groups, had foregone the hacker ethos and had sold out. Later, there are the examples of hackers associated with Anonymous and leaking data from U.S. government contractor HBGary, and North Korean hackers leaking emails stolen from Sony as retribution for the Hollywood comedy, The Interview. Some of the most recent and famous examples are the hack against the now-defunct government spyware pioneer Hacking Team in 2015, and the infamous Russian government-led hack-and-leak of Democratic National Committee emails ahead of the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Iranian government hackers tried to emulate the 2016 playbook during the 2024 elections. Hacktivist A particular kind of hacker who hacks for what they — and perhaps the public — perceive as a good cause, hence the portmanteau of the words “hacker” and “activist.” Hacktivism has been around for more than two decades, starting perhaps with groups like the Cult of the Dead Cow in the late 1990s. Since then, there have been several high profile examples of hacktivist hackers and groups, such as Anonymous, LulzSec, and Phineas Fisher. (Also see: Hacker) Infosec Short for “information security,” an alternative term used to describe defensive cybersecurity focused on the protection of data and information. “Infosec” may be the preferred term for industry veterans, while the term “cybersecurity” has become widely accepted. In modern times, the two terms have become largely interchangeable. Infostealers Infostealers are malware capable of stealing information from a person’s computer or device. Infostealers are often bundled in pirated software, like Redline, which when installed will primarily seek out passwords and other credentials stored in the person’s browser or password manager, then surreptitiously upload the victim’s passwords to the attacker’s systems. This lets the attacker sign in using those stolen passwords. Some infostealers are also capable of stealing session tokens from a user’s browser, which allow the attacker to sign in to a person’s online account as if they were that user but without needing their password or multi-factor authentication code. (See also: Malware) Jailbreak Jailbreaking is used in several contexts to mean the use of exploits and other hacking techniques to circumvent the security of a device, or removing the restrictions a manufacturer puts on hardware or software. In the context of iPhones, for example, a jailbreak is a technique to remove Apple’s restrictions on installing apps outside of its “walled garden” or to gain the ability to conduct security research on Apple devices, which is normally highly restricted. In the context of AI, jailbreaking means figuring out a way to get a chatbot to give out information that it’s not supposed to. Kernel The kernel, as its name suggests, is the core part of an operating system that connects and controls virtually all hardware and software. As such, the kernel has the highest level of privileges, meaning it has access to virtually any data on the device. That’s why, for example, apps such as antivirus and anti-cheat software run at the kernel level, as they require broad access to the device. Having kernel access allows these apps to monitor for malicious code. Malware Malware is a broad umbrella term that describes malicious software. Malware can land in many forms and be used to exploit systems in different ways. As such, malware that is used for specific purposes can often be referred to as its own subcategory. For example, the type of malware used for conducting surveillance on people’s devices is also called “spyware,” while malware that encrypts files and demands money from its victims is called “ransomware.” (See also: Infostealers; Ransomware; Spyware) Metadata is information about something digital, rather than its contents. That can include details about the size of a file or document, who created it, and when, or in the case of digital photos, where the image was taken and information about the device that took the photo. Metadata may not identify the contents of a file, but it can be useful in determining where a document came from or who authored it. Metadata can also refer to information about an exchange, such as who made a call or sent a text message, but not the contents of the call or the message. Multi-factor authentication Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is the common umbrella term for describing when a person must provide a second piece of information, aside from a username and password, to log into a system. MFA (or two-factor; also known as 2FA) can prevent malicious hackers from re-using a person’s stolen credentials by requiring a time-sensitive code sent to or generated from a registered device owned by the account holder, or the use of a physical token or key. Operational security (OPSEC) Operational security, or OPSEC for short, is the practice of keeping information secret in various situations. Practicing OPSEC means thinking about what information you are trying to protect, from whom, and how you’re going to protect it. OPSEC is less about what tools you are using, and more about how you are using them and for what purpose. For example, government officials discussing plans to bomb foreign countries on Signal are practicing bad OPSEC because the app is not designed for that use-case, and runs on devices that are more vulnerable to hackers than highly restricted systems specifically designed for military communications. On the other hand, journalists using Signal to talk to sensitive sources is generally good OPSEC because it makes it harder for those communications to be intercepted by eavesdroppers. (See also: Threat model) Penetration testing Also known as “pen-testing,” this is the process where security researchers “stress-test” the security of a product, network, or system, usually by attempting to modify the way that the product typically operates. Software makers may ask for a pen-test on a product, or of their internal network, to ensure that they are free from serious or critical security vulnerabilities, though a pen-test does not guarantee that a product will be completely bug-free. Phishing Phishing is a type of cyberattack where hackers trick their targets into clicking or tapping on a malicious link, or opening a malicious attachment. The term derives from “fishing,” because hackers often use “lures” to convincingly trick their targets in these types of attacks. A phishing lure could be attachment coming from an email address that appears to be legitimate, or even an email spoofing the email address of a person that the target really knows. Sometimes, the lure could be something that might appear to be important to the target, like sending a forged document to a journalist that appears to show corruption, or a fake conference invite for human rights defenders. There is an often cited adage by the well-known cybersecurity influencer The Grugq, which encapsulates the value of phishing: “Give a man an 0day and he’ll have access for a day, teach a man to phish and he’ll have access for life.” (Also see: Social engineering) Ransomware Ransomware is a type of malicious software (or malware) that prevents device owners from accessing its data, typically by encrypting the person’s files. Ransomware is usually deployed by cybercriminal gangs who demand a ransom payment — usually cryptocurrency — in return for providing the private key to decrypt the person’s data. In some cases, ransomware gangs will steal the victim’s data before encrypting it, allowing the criminals to extort the victim further by threatening to publish the files online. Paying a ransomware gang is no guarantee that the victim will get their stolen data back, or that the gang will delete the stolen data. One of the first-ever ransomware attacks was documented in 1989, in which malware was distributed via floppy disk (an early form of removable storage) to attendees of the World Health Organization’s AIDS conference. Since then, ransomware has evolved into a multibillion-dollar criminal industry as attackers refine their tactics and hone in on big-name corporate victims. (See also: Malware; Sanctions) Remote code execution Remote code execution refers to the ability to run commands or malicious code (such as malware) on a system from over a network, often the internet, without requiring any human interaction from the target. Remote code execution attacks can range in complexity but can be highly damaging when vulnerabilities are exploited. (See also: Arbitrary code execution) Sanctions Cybersecurity-related sanctions work similarly to traditional sanctions in that they make it illegal for businesses or individuals to transact with a sanctioned entity. In the case of cyber sanctions, these entities are suspected of carrying out malicious cyber-enabled activities, such as ransomware attacks or the laundering of ransom payments made to hackers. The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) administers sanctions. The Treasury’s Cyber-Related Sanctions Program was established in 2015 as part of the Obama administration’s response to cyberattacks targeting U.S. government agencies and private sector U.S. entities. While a relatively new addition to the U.S. government’s bureaucratic armory against ransomware groups, sanctions are increasingly used to hamper and deter malicious state actors from conducting cyberattacks. Sanctions are often used against hackers who are out of reach of U.S. indictments or arrest warrants, such as ransomware crews based in Russia. Sandbox A sandbox is a part of a system that is isolated from the rest. The goal is to create a protected environment where a hacker can compromise the sandbox, but without allowing further access to the rest of the system. For example, mobile applications usually run in their own sandboxes. If hackers compromise a browser, for example, they cannot immediately compromise the operating system or another app on the same device. Security researchers also use sandboxes in both physical and virtual environments (such as a virtual machine) to analyze malicious code without risking compromising their own computers or networks. SIM swap SIM swapping is a type of attack where hackers hijack and take control of a person’s phone number, often with the goal of then using the phone number to log into the target’s sensitive accounts, such as their email address, bank account, or cryptocurrency wallet. This attack exploits the way that online accounts sometimes rely on a phone number as a fallback in the event of losing a password. SIM swaps often rely on hackers using social engineering techniques to trick phone carrier employees (or bribing them) into handing over control of a person’s account, as well as hacking into carrier systems. Social engineering is the art of human deception, and encompasses several techniques a hacker can use to deceive their target into doing something they normally would not do. Phishing, for example, can be classified as a type of social engineering attack because hackers trick targets into clicking on a malicious link or opening a malicious attachment, or calling someone on the phone while pretending to be their employer’s IT department. Social engineering can also be used in the real world, for example, to convince building security employees to let someone who shouldn’t be allowed to enter the building. Some call it “human hacking” because social engineering attacks don’t necessarily have to involve technology. (Also see: Phishing) Spyware (commercial, government) A broad term, like malware, that covers a range of surveillance monitoring software. Spyware is typically used to refer to malware made by private companies, such as NSO Group’s Pegasus, Intellexa’s Predator, and Hacking Team’s Remote Control System, among others, which the companies sell to government agencies. In more generic terms, these types of malware are like remote access tools, which allows their operators — usually government agents — to spy and monitor their targets, giving them the ability to access a device’s camera and microphone or exfiltrate data. Spyware is also referred to as commercial or government spyware, or mercenary spyware. (See also: Stalkerware) Stalkerware Stalkerware is a kind of surveillance malware (and a form of spyware) that is usually sold to ordinary consumers under the guise of child or employee monitoring software but is often used for the purposes of spying on the phones of unwitting individuals, oftentimes spouses and domestic partners. The spyware grants access to the target’s messages, location, and more. Stalkerware typically requires physical access to a target’s device, which gives the attacker the ability to install it directly on the target’s device, often because the attacker knows the target’s passcode. (See also: Spyware) Threat model What are you trying to protect? Who are you worried about that could go after you or your data? How could these attackers get to the data? The answers to these kinds of questions are what will lead you to create a threat model. In other words, threat modeling is a process that an organization or an individual has to go through to design software that is secure, and devise techniques to secure it. A threat model can be focused and specific depending on the situation. A human rights activist in an authoritarian country has a different set of adversaries, and data, to protect than a large corporation in a democratic country that is worried about ransomware, for example. (See also: Operational security) When we describe “unauthorized” access, we’re referring to the accessing of a computer system by breaking any of its security features, such as a login prompt or a password, which would be considered illegal under the U.S. Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, or the CFAA. The Supreme Court in 2021 clarified the CFAA, finding that accessing a system lacking any means of authorization — for example, a database with no password — is not illegal, as you cannot break a security feature that isn’t there. It’s worth noting that “unauthorized” is a broadly used term and often used by companies subjectively, and as such has been used to describe malicious hackers who steal someone’s password to break in through to incidents of insider access or abuse by employees. Virtual private network (VPN) A virtual private network, or VPN, is a networking technology that allows someone to “virtually” access a private network, such as their workplace or home, from anywhere else in the world. Many use a VPN provider to browse the web, thinking that this can help to avoid online surveillance. TechCrunch has a skeptics’ guide to VPNs that can help you decide if a VPN makes sense for you. If it does, we’ll show you how to set up your own private and encrypted VPN server that only you control. And if it doesn’t, we explore some of the privacy tools and other measures you can take to meaningfully improve your privacy online. Vulnerability A vulnerability (also referred to as a security flaw) is a type of bug that causes software to crash or behave in an unexpected way that affects the security of the system or its data. Sometimes, two or more vulnerabilities can be used in conjunction with each other — known as “vulnerability chaining” — to gain deeper access to a targeted system. (See also: Bug; Exploit) Zero-click (and one-click) attacks Malicious attacks can sometimes be categorized and described by the amount of user interaction that malware, or a malicious hacker, needs in order to achieve successful compromise. One-click attacks refer to the target having to interact only once with the incoming lure, such as clicking on a malicious link or opening an attachment, to grant the intruder access. But zero-click attacks differ in that they can achieve compromise without the target having to click or tap anything. Zero-clicks are near-invisible to the target and are far more difficult to identify. As such, zero-click attacks are almost always delivered over the internet, and are often reserved for high-value targets for their stealthy capabilities, such as deploying spyware. (Also see: Spyware) Zero-day A zero-day is a specific type of security vulnerability that has been publicly disclosed or exploited but the vendor who makes the affected hardware or software has not been given time (or “zero days”) to fix the problem. As such, there may be no immediate fix or mitigation to prevent an affected system from being compromised. This can be particularly problematic for internet-connected devices. (See also: Vulnerability) First published on September 20, 2024.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 28 Visualizações -

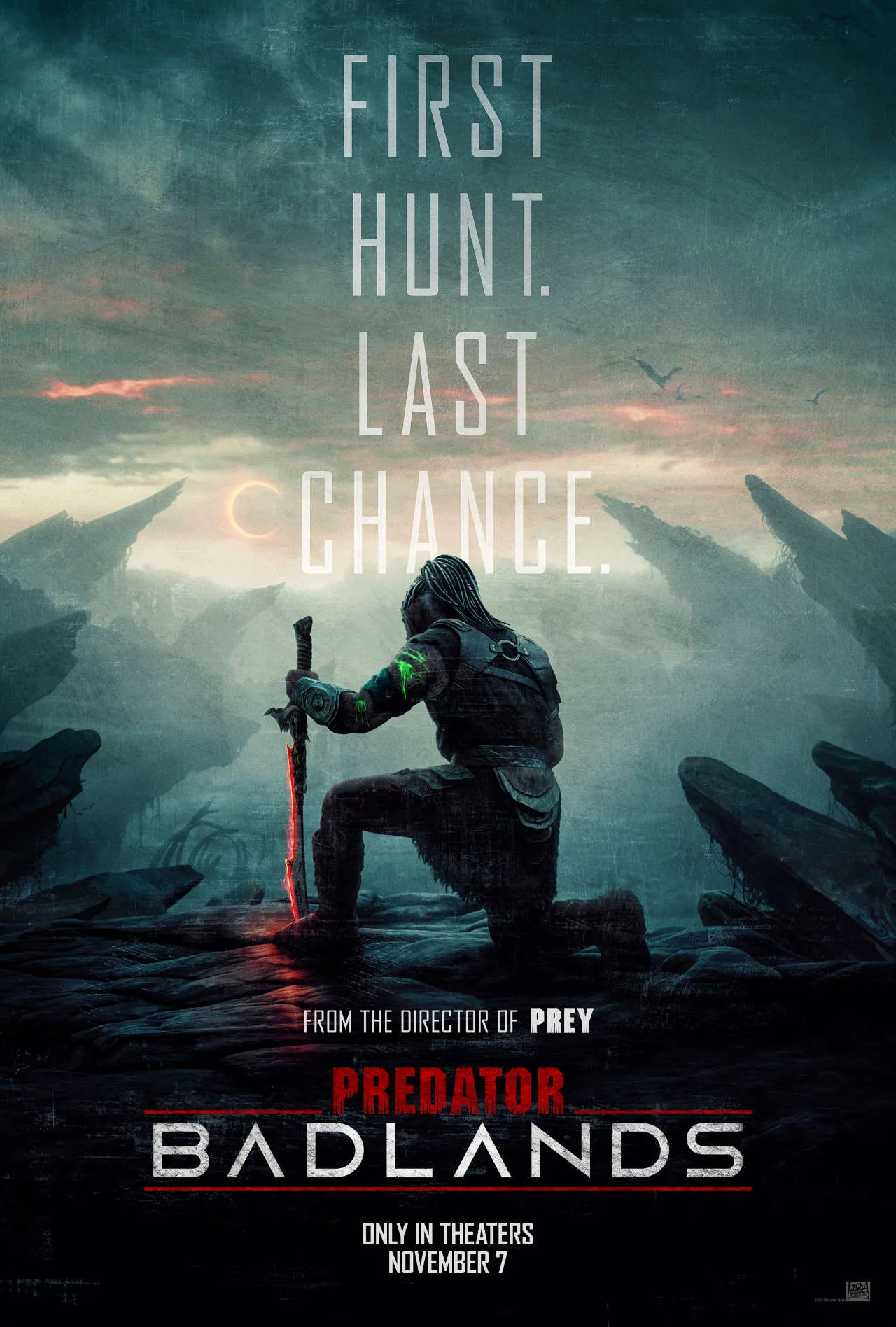

WWW.ARTOFVFX.COMPredator: BadlandsMovie & Games Trailers Predator: Badlands By Vincent Frei - 25/04/2025 The hunt begins on a distant world. Predator: Badlands drops its first trailer — a bold new chapter set in the future, where a young Predator teams up with an unlikely ally to face the deadliest challenge of all. Watch it now! The Production VFX Supervisor is Olivier Dumont. The Production VFX Producer is Kathy Siegel.Director: Dan Trachtenberg Release Date: November 7, 2025 (USA) © Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 20250 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 21 Visualizações

WWW.ARTOFVFX.COMPredator: BadlandsMovie & Games Trailers Predator: Badlands By Vincent Frei - 25/04/2025 The hunt begins on a distant world. Predator: Badlands drops its first trailer — a bold new chapter set in the future, where a young Predator teams up with an unlikely ally to face the deadliest challenge of all. Watch it now! The Production VFX Supervisor is Olivier Dumont. The Production VFX Producer is Kathy Siegel.Director: Dan Trachtenberg Release Date: November 7, 2025 (USA) © Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 20250 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 21 Visualizações -