0 Σχόλια

0 Μοιράστηκε

130 Views

Κατάλογος

Κατάλογος

-

Παρακαλούμε συνδέσου στην Κοινότητά μας για να δηλώσεις τι σου αρέσει, να σχολιάσεις και να μοιραστείς με τους φίλους σου!

-

GAMERANT.COMUnicorn Overlord Dev Comments on PC Port ChancesA PC port of Unicorn Overlord isn't in the pipeline, a senior Vanillaware official has confirmed. The critically acclaimed tactical RPG will hence remain limited to consoles for the foreseeable future, perhaps forever.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 135 Views

GAMERANT.COMUnicorn Overlord Dev Comments on PC Port ChancesA PC port of Unicorn Overlord isn't in the pipeline, a senior Vanillaware official has confirmed. The critically acclaimed tactical RPG will hence remain limited to consoles for the foreseeable future, perhaps forever.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 135 Views -

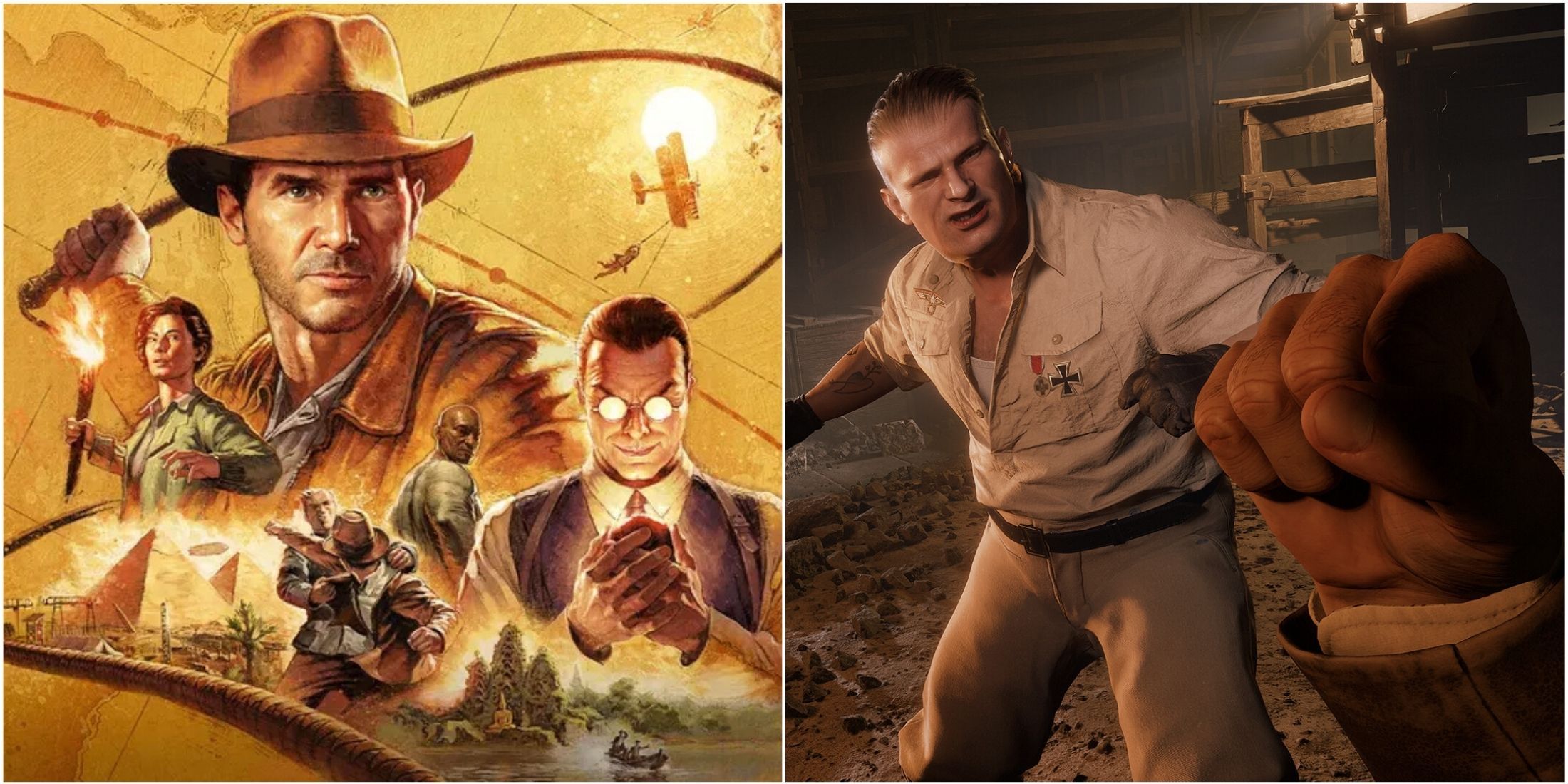

GAMERANT.COMWhat To Do After Beating Indiana Jones And The Great CircleIndiana Jones and the Great Circle might not be a full-fledged open-world title, but it doesnt fully fit the definition of a linear game either. Many of its levels are open-ended, brimming with side content. However, players might not manage to complete all the optional activities before finishing the main story.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 138 Views

GAMERANT.COMWhat To Do After Beating Indiana Jones And The Great CircleIndiana Jones and the Great Circle might not be a full-fledged open-world title, but it doesnt fully fit the definition of a linear game either. Many of its levels are open-ended, brimming with side content. However, players might not manage to complete all the optional activities before finishing the main story.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 138 Views -

BLOG.PLAYSTATION.COMGenshin Impact Version 5.3 adds The Raging Battle ChurnsHello Travelers. The Genshin Impact dev team is delighted to embark on another year of adventures with you in the world of Teyvat. Along with our heartfelt New Years wishes, were excited to share that Version 5.3, Incandescent Ode of Resurrection, will be arriving on January 1. Starting from the first day of 2025, its time to team up with Mavuika, the Pyro Archon, and Citlali, in the final battles against the Abyss looming over Natlan.While the people of Natlan gather to turn the tide of their long war, the people of Liyue reunite for the annual Lantern Rite to embrace a new year. The new character, Lan Yan, and many old friends are waiting in Liyue to light up the night sky with Xiao Lanterns.To spice up the annual celebration, bountiful rewards are available for you to claim, including Primogems 1,600 and the new glider Wings of Fates Course Intertwined via in-game mail, Intertwined Fate 10 via a daily login event, a free 4-star Liyue character via completing the Lantern Rite event, and a new outfit for Xiangling via accumulating Festive Fever in the event.Blaze a radiant path, burn away the shadowy swathsAfter a brief respite, the final battle is at hand. Warriors, blessed by the guidance and protection of the Ode of Resurrection, will stand against the monsters rising from the Abyss in the newest Archon Quest Chapter V: Act V Incandescent Ode of Resurrection. Alongside Mavuika, Citlali, and other warriors, every effort, including the power of the Ruler of Death, will be devoted to banishing the darkness that threatens to swallow the land, no matter the cost. Additionally, the power of Pyro will finally be granted to the Traveler at a pivotal moment.To boost your combat abilities for the final battle, travel to the cave near the Masters of the Night-Wind. There, you will encounter the Wayward Hermetic Spiritspeaker, a powerful Boss, who can move quickly and conjure up multiple clones in battle.Once you have proven your worth, another formidable Weekly Boss the Lord of Eroded Primal Fire, the Abyssal Mimic Dragon awaits your challenge. Additionally, the Pyro Traveler may gain unexpected advantages in this battle.The Radiant Sun and Obsidian StarTwo ladies who will shine in the legendary war to come may be recruited to your party as 5-star playable characters: Mavuika, the Pyro Archon and a claymore wielder, and Citlali, the most powerful shaman of her tribe and a Cryo catalyst user. Both illuminate their peoples paths with centuries of wisdom, exploration, know-how, and battle prowess.From a little girl of the Scions of the Canopy to the Pyro Archon who dazzles and protects all of Natlan like the sun, Mavuikas journey has never been easy. Yet, she never wavered. Upon completing the latest Archon Quest, Mavuikas Story Quest will be unlocked.In combat, Mavuika can crush her opponents with her claymore or charge into battle on her Flamestrider, a one-of-a-kind construct in Teyvat. Her Elemental Skill can summon the All-Fire Armaments, which can take on two forms. Tap to cast Divine Name Unleashed, and the Armaments become Rings of Searing Radiance, following Mavuika or the active character and dealing constant Nightsoul-aligned Pyro DMG. Alternatively, hold to unleash Ancient Name Unbound, transforming her All-Fire Armaments into the Flamestrider. When Mavuika mounts the Flamestrider, she can deal Pyro DMG to opponents in her path. Meanwhile, if nearby party members hit opponents with their Normal Attacks or consume Nightsoul points, she can accumulate Fighting Spirit. When her Fighting Spirit exceeds a certain amount, she can use her Elemental Burst to enter the Nightsouls Blessing state, mounting her Flamestrider to perform a powerful AoE Pyro attack. With her Elemental Burst, Mavuika will also enter the Crucible of Death and Life state, boosting her abilities and making her more resistant to interruption.The Flamestrider is not only a weapon but also a versatile tool for exploration. Equipped with a hidden backup propulsion module, it allows Mavuika to scale cliffs, charge across rugged terrain and waters, and glide in mid-air. In addition, having Mavuika in your party will decrease the partys Nightsoul Transmission cooldown by 20%. The Flamestrider blazes across the land, unrestrained and proud, a testament to her unyielding spirit. Carried on the wind, the memory of a young ladys confident words lingers: I can shoot those cornflakes in your kitchen from right here.The sun shines brilliantly, yet the stars never cease to glow at night. As the most powerful shaman of the Masters of the Night-Wind, Citlali can sense changes in the Ley Lines and feel the wounds across all of Natlan from their long war with the Abyss. Due to the damage sustained by the Night Kingdom in the war, she has been aiding the lost wandering souls who can no longer return to it. In her downtime, the respected Granny Itztli may prefer to stay in her remote abode alone, surrounded by light novels and snacks. She is also accompanied by her little companions Itzpapa and Citlalin, who not only add comfort as cushions and pillows but also provide various forms of support in combat and exploration.In combat, Citlali can deploy shields and summon Itzpapa with her Elemental Skill. When her Nightsoul points exceed a certain amount, Itzpapa will deal AoE Cryo DMG to nearby opponents. Her Elemental Burst summons both little companions and creates a Spiritvessel Skull. When the skull explodes, it will deal Nightsoul-aligned Cryo DMG and restore a fixed amount of Nightsoul points to Citlali. Additionally, when Citlali is in the Nightsouls Blessing state, enemies hit by Frozen or Melt reactions have reduced Pyro and Hydro RES. She can maintain her Nightsouls Blessing state to buff the party when you switch to other characters in battle.Team up for another year of adventureElsewhere in Teyvat, Liyue is currently basking in warmth and harmony as its people prepare for the arrival of Lantern Rite and the new year. In the streets of Liyue, you may encounter a new character, Lan Yan, an Anemo catalyst user, along with many familiar faces, some of whom will debut with fresh new looks in the upcoming update.The new 4-star character, Lan Yan, is a descendant and inheritor of the renowned Qimen Arts. She is a graceful and nimble artisan, lauded as a master craftsman in the Chenyu Vale Artisans Association. In combat, Lan Yan wields the Swallow-Wisp Shield, a secret art passed down through her family for generations. When she dashes forward and hits a target, she leaps backward into the air. Furthermore, this dash attack changes the Elemental Type of her shield to Hydro, Pyro, Cryo, or Electro, allowing it to absorb the corresponding Elemental DMG and deal the corresponding Elemental DMG in return.For Version 5.3 Event Wishes, the first phase will feature the debuts of Mavuika and Citlali, while the second phase brings reruns of Arlecchino and Clorinde, alongside the debut of Lan Yan.To recruit more Liyue characters, players can complete special festival requirements to invite one free 4-star Liyue character, including Lan Yan. Additionally, some 5-star Liyue characters, including Ganyu and others, can be obtained through a new round of Chronicled Wish.More fun events await youMeeting friends is exciting, and participating in fun events doubles the joy. In Lantern Rite, try the mini-game Custom Gift Envelope to design envelopes tailored to your companions unique preferences. Plus, dont forget to create envelopes filled with wishes for friends, family, or other Travelers, sealing your thoughts and memories into these tokens of affection. Also try out Immortal Combat, a Tetris-like game that allows you to use Rattan Figures to gain buffs and defeat opponents. Or try Drills by Lamplight, where you make use of stratagems during battle to boost your score. Dive into these mini-games and gather more Festive Fever to unlock a trove of exciting rewards including Xianglings new outfit, New Years Cheer. Additionally, Hu Taos new outfit, Cherries Snow-Laden, will be on sale with a limited-time discount.The festive cheer manifests through music as well. With Repertoire of Myriad Melodies, the rhythm game feature is now added as a permanent mode and you can start playing, composing, and sharing your custom scores anytime with a special Gadget in your inventory. Want to take on some super-tough battles? In On the Trail of Behemoths, you can take on challenges of different difficulties and face off against four powerful Bosses solo or with a friend.Last but not least, we want to say thank you to everyone who joined us on this fantastic journey in Teyvat! Together, weve created so many wonderful memories. Now, its time to release the Xiao Lanterns and celebrate Lantern Rite again. Its also the perfect moment to ignite your inner fire and boldly embrace the as-yet-unknown, exciting adventures awaiting us in the year ahead.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 199 Views

-

WWW.POLYGON.COMAll tower boss locations and best tower boss order in PalworldPalworld has five bosses locked up in towers scattered around the gigantic map. While you may encounter the first tower boss early on as part of the tutorial, the other five tower bosses are pretty far from the starting area. Beating tower bosses reward you five Ancient Technology Points the first time, which is a pretty good reason to seek these guys out.Below, we list and number all of Palworlds tower bosses in order of difficulty, and have mapped out all tower boss locations on the map below.Palworld tower boss locations and best orderThe map above shows the tower bosses marked in order of recommended completion, based on how much HP each boss has. At a glance, you should tackle tower bosses in this order:Zoe and GrizzboltLily and LyleenAxel and OrserkMarcus and FalerisVictor and ShadowbeakSaya and SelyneBelow, weve listed details about the element, weaknesses, and HP for each tower boss.Tower #1: Zoe and Grizzbolt (Tower of the Rayne Syndicate) locationZoe and Grizzbolt are the first tower boss youll go against and its also the last step of the tutorial.Pal element: ElectricPal weaknesses: GroundHP: Approximately 30,000If you need more help taking down this duo, we have a more in-depth Zoe and Grizzbolt guide.Tower #2: Lily and Lyleen (Tower of the Free Pal Alliance)Lily and Lyleen are in an icy part of the map, so youll want cold resistance gear to help you get there.Pal element: GrassPal weakness: FireHP: Approximately 69,000If you need more help taking down this duo, we have a more in-depth Lily and Lyleen guide.Tower #3: Axel and Orserk (Tower of the Brothers of the Eternal Pyre)Axel and Orserk are on an island filled with lava, so youll need heat resistance to get to the tower.Pal element: Electric/dragonPal weakness: Ground and iceHP: Approximately 130,000Tower #4: Marcus and Faleris (Tower of the PIDF)Marcus and Faleris are in the northern desert, so to get there safely youll need heat resistance during the day and cold resistance at night.Pal element: FirePal weakness: WaterHP: Approximately 146,000Tower #5: Victor and Shadowbeak (Tower of the PAL Genetic Research Unit)Victor and Shadowbeak are at the snowy mountain in the north, so youll need cold resistance to make it there.Pal element: DarkPal weakness: DragonHP: Approximately 200,000Tower #6: Saya and Selyne (Moonflower Tower)Saya and Selyne are the sole tower boss in Sakurajima.Pal element: Dark/neutralPal weakness: Dark and dragonHP: Approximately 261,000For morePalworldguides, weve got you covered. If youre just starting out, weve got abeginners guide, a list ofall Pals, and atype chart. We also have explainers onbreeding,eggs, and a rundown of howmultiplayerworks.On the hunt for resources? Check out our guides on how to getore, coal,polymer,leather,sulfur,wheat seeds,pure quartz,Ancient Technology Points, andancient civilization parts. For advanced players, consult our lists of allpassive skills, allflying mounts, and thebest base locations.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 165 Views

WWW.POLYGON.COMAll tower boss locations and best tower boss order in PalworldPalworld has five bosses locked up in towers scattered around the gigantic map. While you may encounter the first tower boss early on as part of the tutorial, the other five tower bosses are pretty far from the starting area. Beating tower bosses reward you five Ancient Technology Points the first time, which is a pretty good reason to seek these guys out.Below, we list and number all of Palworlds tower bosses in order of difficulty, and have mapped out all tower boss locations on the map below.Palworld tower boss locations and best orderThe map above shows the tower bosses marked in order of recommended completion, based on how much HP each boss has. At a glance, you should tackle tower bosses in this order:Zoe and GrizzboltLily and LyleenAxel and OrserkMarcus and FalerisVictor and ShadowbeakSaya and SelyneBelow, weve listed details about the element, weaknesses, and HP for each tower boss.Tower #1: Zoe and Grizzbolt (Tower of the Rayne Syndicate) locationZoe and Grizzbolt are the first tower boss youll go against and its also the last step of the tutorial.Pal element: ElectricPal weaknesses: GroundHP: Approximately 30,000If you need more help taking down this duo, we have a more in-depth Zoe and Grizzbolt guide.Tower #2: Lily and Lyleen (Tower of the Free Pal Alliance)Lily and Lyleen are in an icy part of the map, so youll want cold resistance gear to help you get there.Pal element: GrassPal weakness: FireHP: Approximately 69,000If you need more help taking down this duo, we have a more in-depth Lily and Lyleen guide.Tower #3: Axel and Orserk (Tower of the Brothers of the Eternal Pyre)Axel and Orserk are on an island filled with lava, so youll need heat resistance to get to the tower.Pal element: Electric/dragonPal weakness: Ground and iceHP: Approximately 130,000Tower #4: Marcus and Faleris (Tower of the PIDF)Marcus and Faleris are in the northern desert, so to get there safely youll need heat resistance during the day and cold resistance at night.Pal element: FirePal weakness: WaterHP: Approximately 146,000Tower #5: Victor and Shadowbeak (Tower of the PAL Genetic Research Unit)Victor and Shadowbeak are at the snowy mountain in the north, so youll need cold resistance to make it there.Pal element: DarkPal weakness: DragonHP: Approximately 200,000Tower #6: Saya and Selyne (Moonflower Tower)Saya and Selyne are the sole tower boss in Sakurajima.Pal element: Dark/neutralPal weakness: Dark and dragonHP: Approximately 261,000For morePalworldguides, weve got you covered. If youre just starting out, weve got abeginners guide, a list ofall Pals, and atype chart. We also have explainers onbreeding,eggs, and a rundown of howmultiplayerworks.On the hunt for resources? Check out our guides on how to getore, coal,polymer,leather,sulfur,wheat seeds,pure quartz,Ancient Technology Points, andancient civilization parts. For advanced players, consult our lists of allpassive skills, allflying mounts, and thebest base locations.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 165 Views -

WWW.POLYGON.COMHow to get Ancient Technology Points in PalworldYoull need Ancient Technology Points to learn how to make essential equipment in Palworld, such as the egg incubator and feed bag. Getting Ancient Technology Points is easier said than done, because youll need to track down difficult bosses and successfully defeat them.Continue on to learn how to get Ancient Technology Points in Palworld, plus a rundown of what you can unlock with them.What are Ancient Technology Points in Palworld?Ancient technology points are a resource that you can use to unlock recipes for gear, weapons, and buildings. They function similarly to skill points, but the method to gaining them is slightly different. Instead of getting an ancient technology point by leveling up, you must hunt down bosses around the map.How to get ancient technology points in PalworldThere are two ways to get ancient technology points defeating tower bosses or Alpha Pal bosses.Tower bossesThere are a total of six tower bosses scattered around Palworld. During the tutorial, youre tasked with facing off against one of the tower bosses, Zoe and Grizzbolt. These fights can be extremely difficult as these tower bosses have an absurd amount of health compared to Pals and even Alpha Pals around the map.After youve defeated the tower boss for the first time, youll receive five Ancient Technology Points. Its important to note that youll only receive ancient technology points after the first time you defeat them.Alpha Pal bossesThere are a total of 44 Alpha Pal bosses littered around Palworld. These fights can take place in the open world or inside of its own instance similar to a dungeon. Alpha Pal bosses can be a little tricky to spot, but they will appear on your map as a circle portrait.The difficulty of Alpha Pal bosses ramps up as you level. For example, one of the first Alpha Pal bosses youll encounter, a level 11 Chillet, is a pretty straight forward boss fight. However, the level 50 Alpha Pal bosses, such as Jetragon and Frostallion, will have you following the five Ds of dodgeball: dodge, dip, duck, dive, and dodge.After youve defeated an Alpha Boss for the first time, youll receive one Ancient Technology Point. Similar to tower bosses, youll only receive an Ancient Technology Point after the first time you defeat them. If you forget if youve already defeated one, check the map to see if there is a check mark over their portrait. The check mark will indicate that you successfully beat them and received the ancient technology point.Treasure chestsIf youre lucky, you can find Ancient Technical Manuals inside treasure chests specifically ones on Wildlife Sanctuary Islands or in dungeons. Youll need to be lucky, as we scoped out about a dozen or so chests before we actually got a manual to drop, but this is the only way to get more Ancient Technology Points if youve cleared out all of the above enemies.Palworld Ancient Technology Points unlock listHeres what you can unlock with Ancient Technology Points at various levels in Palworld.Level 7: Egg IncubatorLevel 10: Small Feed BagLevel 12: Grappling GunLevel 14: Pal Essence CondenserLevel 15: Ore Mining SiteLevel 16: Lockpicking Tool v1Level 17: Mega Grappling GunLevel 19: Ring of MercyLevel 20: Average Feed BagLevel 22: Hip LanternLevel 24: Antique DresserLevel 26: Large Feed BagLevel 28: Lockpicking Tool v2Level 29: Single-shot Sphere LauncherLevel 30: Homeward ThundercloudLevel 31: Ore Mining Site IILevel 32: Giga Grappling GunLevel 33: Summoning AltarLevel 34: Ability GlassesLevel 35: Huge Feed BagLevel 36: Electric Egg IncubatorLevel 37: Meteor LauncherLevel 38: Scatter Sphere LauncherLevel 40: Lilys SpearLevel 42: Decal Gun SetLevel 45: Giant Feed BagLevel 47: Hyper Grappling GunLevel 49: Large Power GeneratorLevel 50: Homing Sphere LauncherLevel 51: Lockpicking Tool v3Level 52: Sulfur MineLevel 53: Coal MineFor morePalworldguides, weve got you covered. If youre just starting out, weve got abeginners guide, a list ofall Pals, and atype chart. We also have explainers onbreeding,eggs, and a rundown of howmultiplayerworks.On the hunt for resources? Check out our guides on how to getore, coal,polymer,leather,sulfur,wheat seeds,pure quartz, andancient civilization parts. For advanced players, consult our lists of alltower boss locations, allpassive skills, allflying mounts, and thebest base locations.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 171 Views

WWW.POLYGON.COMHow to get Ancient Technology Points in PalworldYoull need Ancient Technology Points to learn how to make essential equipment in Palworld, such as the egg incubator and feed bag. Getting Ancient Technology Points is easier said than done, because youll need to track down difficult bosses and successfully defeat them.Continue on to learn how to get Ancient Technology Points in Palworld, plus a rundown of what you can unlock with them.What are Ancient Technology Points in Palworld?Ancient technology points are a resource that you can use to unlock recipes for gear, weapons, and buildings. They function similarly to skill points, but the method to gaining them is slightly different. Instead of getting an ancient technology point by leveling up, you must hunt down bosses around the map.How to get ancient technology points in PalworldThere are two ways to get ancient technology points defeating tower bosses or Alpha Pal bosses.Tower bossesThere are a total of six tower bosses scattered around Palworld. During the tutorial, youre tasked with facing off against one of the tower bosses, Zoe and Grizzbolt. These fights can be extremely difficult as these tower bosses have an absurd amount of health compared to Pals and even Alpha Pals around the map.After youve defeated the tower boss for the first time, youll receive five Ancient Technology Points. Its important to note that youll only receive ancient technology points after the first time you defeat them.Alpha Pal bossesThere are a total of 44 Alpha Pal bosses littered around Palworld. These fights can take place in the open world or inside of its own instance similar to a dungeon. Alpha Pal bosses can be a little tricky to spot, but they will appear on your map as a circle portrait.The difficulty of Alpha Pal bosses ramps up as you level. For example, one of the first Alpha Pal bosses youll encounter, a level 11 Chillet, is a pretty straight forward boss fight. However, the level 50 Alpha Pal bosses, such as Jetragon and Frostallion, will have you following the five Ds of dodgeball: dodge, dip, duck, dive, and dodge.After youve defeated an Alpha Boss for the first time, youll receive one Ancient Technology Point. Similar to tower bosses, youll only receive an Ancient Technology Point after the first time you defeat them. If you forget if youve already defeated one, check the map to see if there is a check mark over their portrait. The check mark will indicate that you successfully beat them and received the ancient technology point.Treasure chestsIf youre lucky, you can find Ancient Technical Manuals inside treasure chests specifically ones on Wildlife Sanctuary Islands or in dungeons. Youll need to be lucky, as we scoped out about a dozen or so chests before we actually got a manual to drop, but this is the only way to get more Ancient Technology Points if youve cleared out all of the above enemies.Palworld Ancient Technology Points unlock listHeres what you can unlock with Ancient Technology Points at various levels in Palworld.Level 7: Egg IncubatorLevel 10: Small Feed BagLevel 12: Grappling GunLevel 14: Pal Essence CondenserLevel 15: Ore Mining SiteLevel 16: Lockpicking Tool v1Level 17: Mega Grappling GunLevel 19: Ring of MercyLevel 20: Average Feed BagLevel 22: Hip LanternLevel 24: Antique DresserLevel 26: Large Feed BagLevel 28: Lockpicking Tool v2Level 29: Single-shot Sphere LauncherLevel 30: Homeward ThundercloudLevel 31: Ore Mining Site IILevel 32: Giga Grappling GunLevel 33: Summoning AltarLevel 34: Ability GlassesLevel 35: Huge Feed BagLevel 36: Electric Egg IncubatorLevel 37: Meteor LauncherLevel 38: Scatter Sphere LauncherLevel 40: Lilys SpearLevel 42: Decal Gun SetLevel 45: Giant Feed BagLevel 47: Hyper Grappling GunLevel 49: Large Power GeneratorLevel 50: Homing Sphere LauncherLevel 51: Lockpicking Tool v3Level 52: Sulfur MineLevel 53: Coal MineFor morePalworldguides, weve got you covered. If youre just starting out, weve got abeginners guide, a list ofall Pals, and atype chart. We also have explainers onbreeding,eggs, and a rundown of howmultiplayerworks.On the hunt for resources? Check out our guides on how to getore, coal,polymer,leather,sulfur,wheat seeds,pure quartz, andancient civilization parts. For advanced players, consult our lists of alltower boss locations, allpassive skills, allflying mounts, and thebest base locations.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 171 Views -

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe best sci-fi movies of 2024We love science fiction here at Polygon. We cover it in games, movies, TV, books whatever medium you can find the genre in, were there.This year has already delivered a lot for fans of the genre, with fascinating stories from around the world for sci-fi faithful in theaters and at home. There have been crowd-pleasing blockbuster hits, contemplative smaller projects, joyous B-movie genre fare, and everything in between.So here are the best sci-fi movies of 2024 so far and where to watch them. They are sorted into two sections: the top tier, cant miss movies of the year, and the best of the rest. This list will continue to be updated throughout the year, and will be sorted in reverse chronological order, so the newest movies always show up first.The cant-miss, top-tier sci-fi movies of 2024The Wild RobotWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVIf an animated sci-fi comedy whose premise lands somewhere tonally and conceptually between The Iron Giant and WALL-E piques your interest, The Wild Robot is absolutely the movie for you. Coming off of the success of recent hits like The Bad Guys and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, Lilo & Stitch director Chris Sanders latest film cements the argument that DreamWorks Animation is in the midst of a renaissance period.After being shipwrecked on an uninhabited island, an intelligent commercial robot (Lupita Nyongo) named ROZZUM Unit 7134, or Roz for short, attempts to ingratiate itself with the islands local wildlife, inadvertently becoming the caretaker for an orphaned baby goose. With painterly animation, densely rendered backgrounds, and emotionally moving storytelling, The Wild Robot is a riveting sci-fi romp bursting with heart and charm aplenty. Toussaint EganRebel Moon: Chalice of BloodWhere to watch: NetflixWhen the first part of Zack Snyders sci-fi epic arrived on Netflix late last year, it was met with criticism over its shallow world and vapid story. However, there was one notable caveat: Snyder himself had already explained that Netflix made him release a shorter, toned-down version of the movie first before he could release his directors cut that better fit his vision. Unsurprisingly for some, now that the directors cut has arrived, its a totally different and infinitely better movie.Rebel Moon: Chalice of Blood, the subtitle for the directors cut of part one, is exactly what Snyder promised the series would be: A tremendous space opera with intricate, complicated lore and tremendous visuals. The story is more or less Seven Samurai in space, which is a perfect prism to use to introduce us to this world. Rebel Moons universe floats exactly in the middle ground between Star Wars and Warhammer, which as it turns out means that everything in the movie is exceptionally cool. Skulls and bones are shoveled into engines to power faster-than-light travel, an unexplained order of red-clad priests collect the teeth of enemies of the horrible fascist Imperium, all in the name of a dead child-god. Its all incredibly metal, and an excellent if very over-the-top space opera, that we should thank our lucky stars for. Austen GoslinFuriosa: A Mad Max SagaWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVThe Mad Max franchise never fails to reinvent itself. Furiosa is a direct prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road, but writer and director George Miller approaches it completely differently than any other Mad Max film so far. Of course, its an outstanding action movie, with action that feels massive, bombastic, and impressive enough to match the mythical framing, but its the storytelling itself that makes Furiosa such a special entry in the sci-fi canon.The story of Furiosas life, and what brought her to be the ruler of the Citadel, takes on a mythic quality, the kind of tall-tale about a legend that gets shared and expanded over a thousand retellings beside fires in the Wasteland. Both Anya Taylor-Joy as Furiosa herself and Chris Hemsworth as Dementus the warlord whose cruelty shaped the course of Furiosas life hand in incredible performances that more than live up to the larger-than-live qualities the story ascribes to them. Thanks to all these details, Furiosa isnt just one of the best action movies of the last decade, its one of the best science fiction prequels ever, too. AGMars ExpressWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVSet in a future where humanity has colonized space and sentient robots live side-by-side with their creators as a caste of servants, Jrmie Prins sci-fi thriller is a gorgeous and fully realized world bursting with imagination and intrigue around every corner.Centered around a pair of private detectives a soft-spoken human woman with a drinking problem and the simulated consciousness of a dead man preserved in an artificial body searching for a missing girl and an elusive hacker, Mars Express slowly but surely unravels into a byzantine mystery where seemingly everyone, and every thing, has a secret to keep. With explosive action sequences, beautifully detailed backgrounds, and a plot that evolves from a simple missing persons case into a singularity-adjacent revelation, Mars Express is an original sci-fi adventure worth experiencing. TEThe BeastWhere to watch: Criterion Channel, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVCloud Atlas meets Mulholland Drive is the most succinct way to describe Bertrand Bonellos sci-fi drama to someone who hasnt seen it yet. Truthfully though, even that comparison falls short in encompassing everything The Beast attempts, and succeeds, at conveying. The surface likeness is uncanny: A story of two lovers, played by La Seydoux and George MacKay, who meet one another time and again across several lifetimes only to be ripped apart from one another.Despite how that might sound, however, The Beast is anything but a fairy tale. A sci-fi odyssey that combines period piece romance with contemporary slasher aesthetics and dystopian dread, Bonellos film is a disorienting and terrifying plunge into a future where love is a liability thats more certain to break your heart than it is to ever make you feel whole. The Beast isnt just one of the best sci-fi films of the year; its one of the most daring movies of the year, period. TEThe Animal KingdomWhere to watch: Hulu, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon/Apple TVOne of the years most fascinating movies, The Animal Kingdom is a French science fiction drama about a mutation that has started to transform some people into human-animal hybrids. The film primarily follows a father (Romain Duris) and his son (Paul Kircher) as they look for the familys missing mother, who is in the midst of just such a transformation.As I wrote in our best movies of the year list:Featuring realistic creature designs that blend practical and digital effects, a rich father-son relationship anchored by strong leading performances, and a compelling overarching narrative metaphor welcoming all sorts of interpretations, The Animal Kingdom stands out in modern sci-fi. It fires on all cylinders to create one of the more powerful movies of the year, evoking a rich world populated by fascinating people.Part of the brilliance of The Animal Kingdom is the continued mundanity of human existence. Yes, everything we thought we knew about our species is being thrown into chaos, but theres still work to do and school to attend and new love and enduring love and all the other shades of the human (or human-animal hybrid) experience. Its in those moments that the true heart of the movie lies. PVDune: Part TwoWhere to watch: Max, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVFrank Herberts Dune has always been a cautionary tale about the fallibility of charismatic leaders, and Denis Villeneuves follow-up to his 2021 epic part-one adaptation of the novel delivers on illustrating that message to chilling and awe-inspiring effect.With his father dead and his enemies now in power, Paul Atreides must earn the trust of the Fremen of Arrakis to rally them to his cause of exacting revenge on the Harkonnens and asserting his claim of supremacy. He is a man at odds with himself: both resistant yet resigned towards embracing a destiny he knows will result in the deaths of millions and cement his own legacy as a tyrant. Dune: Part Two is an epic tragedy disguised as a blockbuster spectacle, a cautionary tale about the perils of fanaticism that inspires you to cheer in awe all the while begging you to question on behalf of who, or what, exactly it is youre cheering for. TEAlienoid: Return to the FutureWhere to watch: Prime Video, Hoopla, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVPart two of the deliriously funny 2022 Korean blockbuster Alienoid, Return to the Future picks up where the first movie left off and delivers a pitch perfect combination of action, comedy, and time-travelling science fiction hijinks.Ill keep the plot details light for those that havent seen the first movie, but the Alienoid movies take place in both the 14th and 21st centuries, following a pair of humanoid robots sent to monitor alien prisoners being held inside human bodies. Along the way, they accidentally adopt a 14th century child and bring her to the modern day.The movie is funny, but it also has impressive visual effects work, and surprisingly strong action sequences for a comedy-forward movie. But the real strength of the Alienoid franchise is the cast, led by the great Kim Tae-ri (The Handmaiden, Space Sweepers) as a pistol-wielding badass in the 14th century, Kim Woo-bin as the robot Guard (a meaty role where he gets to play many different types), and Ryu Jun-yeol as a clumsy 14th century swordsman with a great destiny.Return to the Future does start with a recap of sorts, which is helpful because of how dense the plot is. But its well worth watching both of these very fun movies, which epitomize the kind of crowd-pleasing, cross-genre fun you can have with a blockbuster movie. PVThe best of the restRebel Moon: Curse of Forgiveness Where to watch: NetflixWhile its not nearly as successful as the first part, thanks in part to Chalice of Bloods much more focused scope, part two of Zack Snyders Rebel Moon directors cut is still a pretty great sci-fi romp. More like a sequel than a true part two, Curse of Forgiveness is essentially the last half of Seven Samurai stretched into three hours thanks in large part to an extraordinarily epic hour-plus long battle. If the first Rebel Moon movie is all about world building for Snyder, then the second is all about payoff, giving us glorious action scene after glorious action scene, meticulously paying off the storylines he set up in the original.Of all of these stories, by far the most effective is that of Jimmy, a robot voiced by Anthony Hopkins who was created to serve on a team of personal bodyguards for the late king. The robots were all designed as state of the art killing machines, but once the king died they mysteriously stopped being capable of violence. But over the course of the first two Rebel Moon parts, Jimmy finds something worth fighting for again, and boy does it result in a sick killing montage toward the end of Curse of Forgiveness. If your tolerance for earnestness and silliness in equal measure is as high as your desire for epic sci-fi action, youre sure to love Snyders second run at Rebel Moon and certain to hope he gets the chance to tell more stories in this world. AGA Quiet Place: Day OneWhere to watch: TheatersThe first two Quiet Place movies are surprisingly effective, but it took replacing original director John Krasinski (and him moving to an executive producer and story writer role instead) for the franchise to get its first truly great entry. His replacement director is Michael Sarnoski, who previously directed the Nicolas Cage drama Pig. Sarnoski impressively marries the intimate, character-focused sensibilities that made Pig so fascinating with the kind of blockbuster horror-action youd expect from an alien invasion movie set in Manhattan.Sarnoskis apocalyptic New York is gorgeously shot, with tension waiting in every alley and every noise feeling like certain death. But more than anything its the lead performance by Lupita Nyongo as a terminally ill woman whos still desperately trying to survive that gives A Quiet Place Day One so much life. Its easily the most intimate, low-key, and tragic blockbuster of the year, which turns out to be a perfect mode for the franchise. AGKalki 2898 ADWhere to watch: TheatersThe most expensive Indian film ever made and the highest-grossing Indian film of the year, Kalki 2898 AD is a blockbuster epic in every sense. While it has drawn comparisons to RRR because of the success and scale of that movie, the two really arent all that similar. Kalkis sprawling plot spans from 3102 BC to the titular year, with Hindu deities, post-apocalyptic wastelands, and a ragtag group of heroes brought together to save a woman and her unborn child.While Kalki has excellent vehicle and weapon design and makes some interesting narrative and character choices (especially with the Prabhas lead character, the self-centered bounty hunter Bhairava), the pacing makes the movie very hard to follow, and the directing and editing choices dont help at all. Its also a movie very focused on human cruelty, so expect a lot of that. But strangely, despite not really liking Kalki all that much, I cant wait for the next entry in this series. The production design is evocative, and the movie ends in a much more interesting place than it starts. While its not a great movie, it has the bones of a great franchise. PVRobot DreamsWhere to watch: TheatersNominated for a surprise Best Animated Feature Oscar at this years Academy Awards, Robot Dreams finally rolled out to wider audiences this May.As our colleague Petrana Radulovic put it in our list of the best movies of the year:Director Pablo Bergerwas so dang moved by Sara Varons graphic novel Robot Dreams that he started an animation studio to make it into a movie. Told entirely without dialogue,Robot Dreamsis about a lonely dog who befriends a robot and the whirlwind summer they spend together before life forces them apart. The characters are evocative and the anthropomorphic world is very charming. But despite the humanized animals, this isnt a goofy, gag-filled movie;Robot Dreamsis actually an incredibly poignant and bittersweet film all about the meaningful friendships that we cant always take with us as life goes on. The last scenes hit like a gut punch, aching in the best sort of way.Kingdom of the Planet of the ApesWhere to watch: Hulu, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVThe fourth entry in a Planet of the Apes prequel series sounds awfully bleak on paper, but the reality of Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes couldnt be further from the truth. The latest entry in the franchise, directed by Maze Runner filmmaker Wes Ball, is a fantastical adventure that proves to be the most fun Apes movie in years. While the previous two movies were both dour meditations on war, combat, and the limitations of peaceful coexistence, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is a fun action/adventure movie that feels pulled right out of the 90s.It follows a young ape named Noa who has to go on a quest to save his village after his friends and family get kidnapped. That journey takes Noa around the ruins of the once great human world, and shows us how the apes have been attempting to build civilizations of their own. All of this makes for excellent world building, and a surprisingly effective prequel to the future imagined in the original Planet of the Apes movies. AGCode 8: Part IIWhere to watch: NetflixIn 2020, a small Canadian sci-fi movie supported by more than 30,000 Indiegogo contributors dropped on Netflix. Code 8, produced by and starring real-life cousins Robbie Amell (Upload) and Stephen Amell (Arrow), would become a breakaway hit on the platform, helping spawn a straight-to-Netflix sequel a few years later. Its easy to see why they became hits their dedication to interesting world-building and the clear passion behind the projects make them enjoyable to watch, warts and all.In the world of Code 8, superpowered people have existed since the early 20th century. Those people became a labor class, using their powers to perform dangerous jobs. But as the Industrial Revolution progressed and automation became more standard, society decided the dangers of superpowered workers outweighed the benefits, turning those former workers into a heavily policed and marginalized class of people. When a young man with electric powers looks for a job to help pay for his mothers medical bills, he falls in with a gang of powered criminals looking to secure a big score.The Code 8 movies are not the most polished projects. But in some ways, that works to their benefit, in concert with the low-budget passion indie mood of the projects. (It also makes you appreciate how good the evil robot cops look in the series some are reminiscent of Automatons in Helldivers 2, while others are straight riffs on Boston Dynamics terrifying robot dogs).Part heist movies, part sci-fi, part stories about power and who wields it, the Code 8 movies dont always execute at a high level, but they are working with some interesting ideas and are committed to seeing them through. Sometimes, thats what you want from low-budget sci-fi. PV Badland HuntersWhere to watch: NetflixWhen youre looking for a great sci-fi movie to watch, sometimes youre looking for a thoughtful meditation on humanitys role in the galaxy, with hard science elements and beautiful, almost fantastical cinematography. Other times, youre looking for Ma Dong-seok absolutely laying into fools in a post-apocalyptic hellscape. Badland Hunters is for those other times.A (bizarre, tonally speaking) sequel to the serious apocalyptic earthquake drama Concrete Utopia, Badland Hunters is a Mad Max-esque story of a hulking man looking out for his found family and destroying anyone who gets in his way (including a mad scientist up to some twisted experiments). While it doesnt reach the high heights of Mas work in Train to Busan or the Roundup movies, he is such a reliably entertaining and charismatic movie star that you cant help but enjoy this B-movie experience. (And director Heo Myeong-haeng, a former stuntman who will helm the upcoming The Roundup: Punishment, knows exactly how to shoot the big mans action sequences.) Its one of Netflixs standout international releases of 2024 so far, and a fun time for people looking for some popcorn-worthy sci-fi. PVJustice League: Crisis on Infinite Earths Part OneWhere to watch: MaxThe second phase of the DC Animated Movie Universe is wrapping up with the three-part Crisis on Infinite Earths storyline all three have been released, but only the first two are on Max. I havent seen the third yet, but enjoyed the first in the context of DCAU projects (the second felt less strong, but Im still excited for when the third one arrives on the streaming platform).Presented in a nonlinear narrative as Barry Allen trips around time, Crisis on Infinite Earths Part One takes more chances with its story than other DCAU projects, and they pay off. Barry travels to multiple Earths and meets multiple versions of the Justice League superheroes, learning of an anti-matter wave that threatens the entire multi-verse. Its pulpy, comic book fun with a game voice cast (Darren Criss as Superman, Jensen Ackles as Batman, Matt Bomer as Flash, Zachary Quinto as Lex Luthor the list goes on), and its more sci-fi forward than many other DC animated movies.And some teases for the other entries: Part Two features Terry McGinnis from Batman Beyond, and Part Three features the posthumous final performance of the great Kevin Conroy as Batman, as well as the final performance of Mark Hamill as the Joker. PV0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 170 Views

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe best sci-fi movies of 2024We love science fiction here at Polygon. We cover it in games, movies, TV, books whatever medium you can find the genre in, were there.This year has already delivered a lot for fans of the genre, with fascinating stories from around the world for sci-fi faithful in theaters and at home. There have been crowd-pleasing blockbuster hits, contemplative smaller projects, joyous B-movie genre fare, and everything in between.So here are the best sci-fi movies of 2024 so far and where to watch them. They are sorted into two sections: the top tier, cant miss movies of the year, and the best of the rest. This list will continue to be updated throughout the year, and will be sorted in reverse chronological order, so the newest movies always show up first.The cant-miss, top-tier sci-fi movies of 2024The Wild RobotWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVIf an animated sci-fi comedy whose premise lands somewhere tonally and conceptually between The Iron Giant and WALL-E piques your interest, The Wild Robot is absolutely the movie for you. Coming off of the success of recent hits like The Bad Guys and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, Lilo & Stitch director Chris Sanders latest film cements the argument that DreamWorks Animation is in the midst of a renaissance period.After being shipwrecked on an uninhabited island, an intelligent commercial robot (Lupita Nyongo) named ROZZUM Unit 7134, or Roz for short, attempts to ingratiate itself with the islands local wildlife, inadvertently becoming the caretaker for an orphaned baby goose. With painterly animation, densely rendered backgrounds, and emotionally moving storytelling, The Wild Robot is a riveting sci-fi romp bursting with heart and charm aplenty. Toussaint EganRebel Moon: Chalice of BloodWhere to watch: NetflixWhen the first part of Zack Snyders sci-fi epic arrived on Netflix late last year, it was met with criticism over its shallow world and vapid story. However, there was one notable caveat: Snyder himself had already explained that Netflix made him release a shorter, toned-down version of the movie first before he could release his directors cut that better fit his vision. Unsurprisingly for some, now that the directors cut has arrived, its a totally different and infinitely better movie.Rebel Moon: Chalice of Blood, the subtitle for the directors cut of part one, is exactly what Snyder promised the series would be: A tremendous space opera with intricate, complicated lore and tremendous visuals. The story is more or less Seven Samurai in space, which is a perfect prism to use to introduce us to this world. Rebel Moons universe floats exactly in the middle ground between Star Wars and Warhammer, which as it turns out means that everything in the movie is exceptionally cool. Skulls and bones are shoveled into engines to power faster-than-light travel, an unexplained order of red-clad priests collect the teeth of enemies of the horrible fascist Imperium, all in the name of a dead child-god. Its all incredibly metal, and an excellent if very over-the-top space opera, that we should thank our lucky stars for. Austen GoslinFuriosa: A Mad Max SagaWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVThe Mad Max franchise never fails to reinvent itself. Furiosa is a direct prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road, but writer and director George Miller approaches it completely differently than any other Mad Max film so far. Of course, its an outstanding action movie, with action that feels massive, bombastic, and impressive enough to match the mythical framing, but its the storytelling itself that makes Furiosa such a special entry in the sci-fi canon.The story of Furiosas life, and what brought her to be the ruler of the Citadel, takes on a mythic quality, the kind of tall-tale about a legend that gets shared and expanded over a thousand retellings beside fires in the Wasteland. Both Anya Taylor-Joy as Furiosa herself and Chris Hemsworth as Dementus the warlord whose cruelty shaped the course of Furiosas life hand in incredible performances that more than live up to the larger-than-live qualities the story ascribes to them. Thanks to all these details, Furiosa isnt just one of the best action movies of the last decade, its one of the best science fiction prequels ever, too. AGMars ExpressWhere to watch: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVSet in a future where humanity has colonized space and sentient robots live side-by-side with their creators as a caste of servants, Jrmie Prins sci-fi thriller is a gorgeous and fully realized world bursting with imagination and intrigue around every corner.Centered around a pair of private detectives a soft-spoken human woman with a drinking problem and the simulated consciousness of a dead man preserved in an artificial body searching for a missing girl and an elusive hacker, Mars Express slowly but surely unravels into a byzantine mystery where seemingly everyone, and every thing, has a secret to keep. With explosive action sequences, beautifully detailed backgrounds, and a plot that evolves from a simple missing persons case into a singularity-adjacent revelation, Mars Express is an original sci-fi adventure worth experiencing. TEThe BeastWhere to watch: Criterion Channel, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVCloud Atlas meets Mulholland Drive is the most succinct way to describe Bertrand Bonellos sci-fi drama to someone who hasnt seen it yet. Truthfully though, even that comparison falls short in encompassing everything The Beast attempts, and succeeds, at conveying. The surface likeness is uncanny: A story of two lovers, played by La Seydoux and George MacKay, who meet one another time and again across several lifetimes only to be ripped apart from one another.Despite how that might sound, however, The Beast is anything but a fairy tale. A sci-fi odyssey that combines period piece romance with contemporary slasher aesthetics and dystopian dread, Bonellos film is a disorienting and terrifying plunge into a future where love is a liability thats more certain to break your heart than it is to ever make you feel whole. The Beast isnt just one of the best sci-fi films of the year; its one of the most daring movies of the year, period. TEThe Animal KingdomWhere to watch: Hulu, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon/Apple TVOne of the years most fascinating movies, The Animal Kingdom is a French science fiction drama about a mutation that has started to transform some people into human-animal hybrids. The film primarily follows a father (Romain Duris) and his son (Paul Kircher) as they look for the familys missing mother, who is in the midst of just such a transformation.As I wrote in our best movies of the year list:Featuring realistic creature designs that blend practical and digital effects, a rich father-son relationship anchored by strong leading performances, and a compelling overarching narrative metaphor welcoming all sorts of interpretations, The Animal Kingdom stands out in modern sci-fi. It fires on all cylinders to create one of the more powerful movies of the year, evoking a rich world populated by fascinating people.Part of the brilliance of The Animal Kingdom is the continued mundanity of human existence. Yes, everything we thought we knew about our species is being thrown into chaos, but theres still work to do and school to attend and new love and enduring love and all the other shades of the human (or human-animal hybrid) experience. Its in those moments that the true heart of the movie lies. PVDune: Part TwoWhere to watch: Max, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVFrank Herberts Dune has always been a cautionary tale about the fallibility of charismatic leaders, and Denis Villeneuves follow-up to his 2021 epic part-one adaptation of the novel delivers on illustrating that message to chilling and awe-inspiring effect.With his father dead and his enemies now in power, Paul Atreides must earn the trust of the Fremen of Arrakis to rally them to his cause of exacting revenge on the Harkonnens and asserting his claim of supremacy. He is a man at odds with himself: both resistant yet resigned towards embracing a destiny he knows will result in the deaths of millions and cement his own legacy as a tyrant. Dune: Part Two is an epic tragedy disguised as a blockbuster spectacle, a cautionary tale about the perils of fanaticism that inspires you to cheer in awe all the while begging you to question on behalf of who, or what, exactly it is youre cheering for. TEAlienoid: Return to the FutureWhere to watch: Prime Video, Hoopla, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVPart two of the deliriously funny 2022 Korean blockbuster Alienoid, Return to the Future picks up where the first movie left off and delivers a pitch perfect combination of action, comedy, and time-travelling science fiction hijinks.Ill keep the plot details light for those that havent seen the first movie, but the Alienoid movies take place in both the 14th and 21st centuries, following a pair of humanoid robots sent to monitor alien prisoners being held inside human bodies. Along the way, they accidentally adopt a 14th century child and bring her to the modern day.The movie is funny, but it also has impressive visual effects work, and surprisingly strong action sequences for a comedy-forward movie. But the real strength of the Alienoid franchise is the cast, led by the great Kim Tae-ri (The Handmaiden, Space Sweepers) as a pistol-wielding badass in the 14th century, Kim Woo-bin as the robot Guard (a meaty role where he gets to play many different types), and Ryu Jun-yeol as a clumsy 14th century swordsman with a great destiny.Return to the Future does start with a recap of sorts, which is helpful because of how dense the plot is. But its well worth watching both of these very fun movies, which epitomize the kind of crowd-pleasing, cross-genre fun you can have with a blockbuster movie. PVThe best of the restRebel Moon: Curse of Forgiveness Where to watch: NetflixWhile its not nearly as successful as the first part, thanks in part to Chalice of Bloods much more focused scope, part two of Zack Snyders Rebel Moon directors cut is still a pretty great sci-fi romp. More like a sequel than a true part two, Curse of Forgiveness is essentially the last half of Seven Samurai stretched into three hours thanks in large part to an extraordinarily epic hour-plus long battle. If the first Rebel Moon movie is all about world building for Snyder, then the second is all about payoff, giving us glorious action scene after glorious action scene, meticulously paying off the storylines he set up in the original.Of all of these stories, by far the most effective is that of Jimmy, a robot voiced by Anthony Hopkins who was created to serve on a team of personal bodyguards for the late king. The robots were all designed as state of the art killing machines, but once the king died they mysteriously stopped being capable of violence. But over the course of the first two Rebel Moon parts, Jimmy finds something worth fighting for again, and boy does it result in a sick killing montage toward the end of Curse of Forgiveness. If your tolerance for earnestness and silliness in equal measure is as high as your desire for epic sci-fi action, youre sure to love Snyders second run at Rebel Moon and certain to hope he gets the chance to tell more stories in this world. AGA Quiet Place: Day OneWhere to watch: TheatersThe first two Quiet Place movies are surprisingly effective, but it took replacing original director John Krasinski (and him moving to an executive producer and story writer role instead) for the franchise to get its first truly great entry. His replacement director is Michael Sarnoski, who previously directed the Nicolas Cage drama Pig. Sarnoski impressively marries the intimate, character-focused sensibilities that made Pig so fascinating with the kind of blockbuster horror-action youd expect from an alien invasion movie set in Manhattan.Sarnoskis apocalyptic New York is gorgeously shot, with tension waiting in every alley and every noise feeling like certain death. But more than anything its the lead performance by Lupita Nyongo as a terminally ill woman whos still desperately trying to survive that gives A Quiet Place Day One so much life. Its easily the most intimate, low-key, and tragic blockbuster of the year, which turns out to be a perfect mode for the franchise. AGKalki 2898 ADWhere to watch: TheatersThe most expensive Indian film ever made and the highest-grossing Indian film of the year, Kalki 2898 AD is a blockbuster epic in every sense. While it has drawn comparisons to RRR because of the success and scale of that movie, the two really arent all that similar. Kalkis sprawling plot spans from 3102 BC to the titular year, with Hindu deities, post-apocalyptic wastelands, and a ragtag group of heroes brought together to save a woman and her unborn child.While Kalki has excellent vehicle and weapon design and makes some interesting narrative and character choices (especially with the Prabhas lead character, the self-centered bounty hunter Bhairava), the pacing makes the movie very hard to follow, and the directing and editing choices dont help at all. Its also a movie very focused on human cruelty, so expect a lot of that. But strangely, despite not really liking Kalki all that much, I cant wait for the next entry in this series. The production design is evocative, and the movie ends in a much more interesting place than it starts. While its not a great movie, it has the bones of a great franchise. PVRobot DreamsWhere to watch: TheatersNominated for a surprise Best Animated Feature Oscar at this years Academy Awards, Robot Dreams finally rolled out to wider audiences this May.As our colleague Petrana Radulovic put it in our list of the best movies of the year:Director Pablo Bergerwas so dang moved by Sara Varons graphic novel Robot Dreams that he started an animation studio to make it into a movie. Told entirely without dialogue,Robot Dreamsis about a lonely dog who befriends a robot and the whirlwind summer they spend together before life forces them apart. The characters are evocative and the anthropomorphic world is very charming. But despite the humanized animals, this isnt a goofy, gag-filled movie;Robot Dreamsis actually an incredibly poignant and bittersweet film all about the meaningful friendships that we cant always take with us as life goes on. The last scenes hit like a gut punch, aching in the best sort of way.Kingdom of the Planet of the ApesWhere to watch: Hulu, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TVThe fourth entry in a Planet of the Apes prequel series sounds awfully bleak on paper, but the reality of Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes couldnt be further from the truth. The latest entry in the franchise, directed by Maze Runner filmmaker Wes Ball, is a fantastical adventure that proves to be the most fun Apes movie in years. While the previous two movies were both dour meditations on war, combat, and the limitations of peaceful coexistence, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is a fun action/adventure movie that feels pulled right out of the 90s.It follows a young ape named Noa who has to go on a quest to save his village after his friends and family get kidnapped. That journey takes Noa around the ruins of the once great human world, and shows us how the apes have been attempting to build civilizations of their own. All of this makes for excellent world building, and a surprisingly effective prequel to the future imagined in the original Planet of the Apes movies. AGCode 8: Part IIWhere to watch: NetflixIn 2020, a small Canadian sci-fi movie supported by more than 30,000 Indiegogo contributors dropped on Netflix. Code 8, produced by and starring real-life cousins Robbie Amell (Upload) and Stephen Amell (Arrow), would become a breakaway hit on the platform, helping spawn a straight-to-Netflix sequel a few years later. Its easy to see why they became hits their dedication to interesting world-building and the clear passion behind the projects make them enjoyable to watch, warts and all.In the world of Code 8, superpowered people have existed since the early 20th century. Those people became a labor class, using their powers to perform dangerous jobs. But as the Industrial Revolution progressed and automation became more standard, society decided the dangers of superpowered workers outweighed the benefits, turning those former workers into a heavily policed and marginalized class of people. When a young man with electric powers looks for a job to help pay for his mothers medical bills, he falls in with a gang of powered criminals looking to secure a big score.The Code 8 movies are not the most polished projects. But in some ways, that works to their benefit, in concert with the low-budget passion indie mood of the projects. (It also makes you appreciate how good the evil robot cops look in the series some are reminiscent of Automatons in Helldivers 2, while others are straight riffs on Boston Dynamics terrifying robot dogs).Part heist movies, part sci-fi, part stories about power and who wields it, the Code 8 movies dont always execute at a high level, but they are working with some interesting ideas and are committed to seeing them through. Sometimes, thats what you want from low-budget sci-fi. PV Badland HuntersWhere to watch: NetflixWhen youre looking for a great sci-fi movie to watch, sometimes youre looking for a thoughtful meditation on humanitys role in the galaxy, with hard science elements and beautiful, almost fantastical cinematography. Other times, youre looking for Ma Dong-seok absolutely laying into fools in a post-apocalyptic hellscape. Badland Hunters is for those other times.A (bizarre, tonally speaking) sequel to the serious apocalyptic earthquake drama Concrete Utopia, Badland Hunters is a Mad Max-esque story of a hulking man looking out for his found family and destroying anyone who gets in his way (including a mad scientist up to some twisted experiments). While it doesnt reach the high heights of Mas work in Train to Busan or the Roundup movies, he is such a reliably entertaining and charismatic movie star that you cant help but enjoy this B-movie experience. (And director Heo Myeong-haeng, a former stuntman who will helm the upcoming The Roundup: Punishment, knows exactly how to shoot the big mans action sequences.) Its one of Netflixs standout international releases of 2024 so far, and a fun time for people looking for some popcorn-worthy sci-fi. PVJustice League: Crisis on Infinite Earths Part OneWhere to watch: MaxThe second phase of the DC Animated Movie Universe is wrapping up with the three-part Crisis on Infinite Earths storyline all three have been released, but only the first two are on Max. I havent seen the third yet, but enjoyed the first in the context of DCAU projects (the second felt less strong, but Im still excited for when the third one arrives on the streaming platform).Presented in a nonlinear narrative as Barry Allen trips around time, Crisis on Infinite Earths Part One takes more chances with its story than other DCAU projects, and they pay off. Barry travels to multiple Earths and meets multiple versions of the Justice League superheroes, learning of an anti-matter wave that threatens the entire multi-verse. Its pulpy, comic book fun with a game voice cast (Darren Criss as Superman, Jensen Ackles as Batman, Matt Bomer as Flash, Zachary Quinto as Lex Luthor the list goes on), and its more sci-fi forward than many other DC animated movies.And some teases for the other entries: Part Two features Terry McGinnis from Batman Beyond, and Part Three features the posthumous final performance of the great Kevin Conroy as Batman, as well as the final performance of Mark Hamill as the Joker. PV0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 170 Views -

DESIGN-MILK.COMThe New Level Lock+ (Matter) Revolutionizes Home SecurityBuilding smart devices into your home doesnt have to mean sacrificing design. Many current and previous generation smart locks are bulky and unattractive, but companies like Level are creating sleek and minimalistic options that blend seamlessly with any home decor. Level has been at the forefront of smart lock design for some time now, and the new Level Lock+ (Matter) continues this trend, offering robust features while maintaining its stylish design.At first glance, the Level Lock+ (Matter) looks identical to its predecessor, the Level Lock+. Thats a good thing, though. The Level Lock+ is sleek and stylish, and nothing about the exterior of the lock makes it seem as though its actually a smart lock. Both the exterior and the interior portions of the lock look like any other standard locking mechanism, albeit a well-designed one at that.The most notable update in the Level Lock+ (Matter) is its support for Matter, a unified smart home standard developed by industry leaders like Apple, Google, and Amazon. Matter ensures seamless integration with any modern smart home ecosystem, eliminating the need to check for compatibility with specific platforms. Whether you use Apple HomeKit, Google Home, or Alexa, the Level Lock+ (Matter) fits right in.In addition to Matter support, the lock offers several convenient features. Notably, it works with Apple Home Keys, allowing you to simply tap your iPhone to the lock when you get home to unlock it. It also works with the Level Keypad, which is sold separately but can be installed outside your door so that you can input a code to enter, and more importantly, it allows you to set up guest codes that you can give to someone who might only need to access your home one time, for example. Lastly, you can use it with a key fob.Smart locks like the Level Lock+ (Matter) offer practical benefits. They let you control your lock from your phone and, when connected to a smart home hub, provide remote access from anywhere with an internet connection. Installation is straightforward, making it accessible even for DIY enthusiasts.Available in Satin Nickel or Matte Black, the Level Lock+ (Matter) is available for $329 via level.co.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 175 Views

DESIGN-MILK.COMThe New Level Lock+ (Matter) Revolutionizes Home SecurityBuilding smart devices into your home doesnt have to mean sacrificing design. Many current and previous generation smart locks are bulky and unattractive, but companies like Level are creating sleek and minimalistic options that blend seamlessly with any home decor. Level has been at the forefront of smart lock design for some time now, and the new Level Lock+ (Matter) continues this trend, offering robust features while maintaining its stylish design.At first glance, the Level Lock+ (Matter) looks identical to its predecessor, the Level Lock+. Thats a good thing, though. The Level Lock+ is sleek and stylish, and nothing about the exterior of the lock makes it seem as though its actually a smart lock. Both the exterior and the interior portions of the lock look like any other standard locking mechanism, albeit a well-designed one at that.The most notable update in the Level Lock+ (Matter) is its support for Matter, a unified smart home standard developed by industry leaders like Apple, Google, and Amazon. Matter ensures seamless integration with any modern smart home ecosystem, eliminating the need to check for compatibility with specific platforms. Whether you use Apple HomeKit, Google Home, or Alexa, the Level Lock+ (Matter) fits right in.In addition to Matter support, the lock offers several convenient features. Notably, it works with Apple Home Keys, allowing you to simply tap your iPhone to the lock when you get home to unlock it. It also works with the Level Keypad, which is sold separately but can be installed outside your door so that you can input a code to enter, and more importantly, it allows you to set up guest codes that you can give to someone who might only need to access your home one time, for example. Lastly, you can use it with a key fob.Smart locks like the Level Lock+ (Matter) offer practical benefits. They let you control your lock from your phone and, when connected to a smart home hub, provide remote access from anywhere with an internet connection. Installation is straightforward, making it accessible even for DIY enthusiasts.Available in Satin Nickel or Matte Black, the Level Lock+ (Matter) is available for $329 via level.co.0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 175 Views -

DESIGN-MILK.COMTop 10 Friday Five Posts of 202410. Larry Booth Shares the Places + Spaces That Captivate Him + MoreLarry Booths natural flair for design and architectural convictions have garnered him some 50+ years of professional practice where he has significantly contributed to Chicagos cultural landscape in addition to the broader academic arena. As the founder and principal/director of Booth Hansen, he has led by example proving that robust design solutions come from an open and organized collaborative studio.9. Alda Ly Revels in Reeded Glass, Icelandic Baths + MoreArchitect Alda Ly continues to assemble a portfolio of meaningful work designing for entrepreneurs and startups with her practice ALA Studio. She has a storied history of socially conscious contributions to the field and employs ethnographic research to inform her concepts. Though Lys practice tackles a wide range of projects, each space is imbued with a sense of play and reflective of her deep consideration for the clients human experience.8. Hadiya Williams on Connections, a Love of Old Objects+ MoreThe tendrils of graphic thinking extend into almost every other facet of design, as evidenced by the work of Hadiya Williams and her design studio Black Pepper Paperie Co. She draws from two decades of experience in the graphic arts to inform fresh objects in the realm of ceramics and surface design. Whats more, her work builds on a storied tradition of West African art and textiles while referencing the Black Arts Movement and the early 20th century Harlem Renaissance.7. Susan Maddux Shares Her Vintage Textiles, Art Collection + MoreLos Angeles-based artist Susan Maddux makes works that are an incredible three-dimensional experience drawing. Her origami-inspired technique transforms paintings into oversized wall sculptures through experimentation with proportion and patterning. The work also connects Maddux a 4th generation Hapa-Japanese woman to generations of artisans who came before her.6. Kate Rohrer on Jumpsuits, Earthy Scents + MoreCreative practice is inextricably linked to life experience. And for interior designer Kate Rohrer, her time waiting tables and pouring cocktails in the food service industry still informs the way she approaches hospitality projects. Her firm ROHE Creative is responsible for some exhilarating spaces thanks to Rohrers unabashed use of color and penchant for rich textures seamlessly blending disparate styles into unique personal narratives.5. Sarah Jefferys Prizes Sustainable Design, Lots of Natural Light + MorePassive house design, net zero goals, and sustainability. These things might sound like headaches for some, but for Sarah Jefferys who leads her namesake firm, Sarah Jefferys Architecture + Interiors they are the impetus to arrive at the most robust design solution for people and the planet. An expert in her field with over 20 years of experience, Jefferys is on a mission to reach net zero on all her studios projects within the next decade.4. George Smart on His Favorite Modernist Residential ArchitectureHaving defected from a career in consulting, George Smart set on a new path to pay it forward. While researching design precedents for a new family home, he noticed the lack of reputable online sources for the everyman. He decided to build his own repository, which marked the founding of NCModernist, and later USModernist the worlds largest nonprofit educational archive dedicated to the documentation, preservation, and promotion of Modernist residential design.3. Brigette Romanek Loves Alaia Dresses, Soulful Books + MoreGwyneth Paltrow, Demi Moore, Joe Jonas, Christian Bale, Beyonc, and Jay-Z. While celebrity may be one throughline connecting these stars, interior designer Brigette Romanek is another. The award-winning creative started styling interiors roughly a decade ago and has already grown her creative practice into a highly sought after design studio now stepping into the realm of product design.2. Kickie Chudikova Loves the Art of Scent, Issey Miyake + MoreIndustrial designer Kickie Chudikovas curiosity for artful objects is exercised in the design of every product, home furnishing, and artifact she manufactures with the hopes that it will provide their owners with enrichment or fulfillment for a lifetime. Chudikova has never limited herself in material palette or by color, always looking for a solution that invites interaction, with future aspirations to tackle food.And the most popular Friday Five post of 2024 is1. Dale Chihuly Shares His Favorite Architect + Beloved CollectionsGlass is enchanting, and for master of his craft Dale Chihuly, the mediums properties are incomparable. His work includes more than 200 museum collections worldwide and his rsum is equally as decorated. It boasts many accolades including two fellowships, 13 honorary doctorates, and title as co-founder of the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington State. Chihuly is one of few leading the development of this industry into the future.Check out the rest of Design Milks end of the year coverage here!0 Σχόλια 0 Μοιράστηκε 179 Views