0 Комментарии

0 Поделились

Каталог

Каталог

-

Войдите, чтобы отмечать, делиться и комментировать!

-

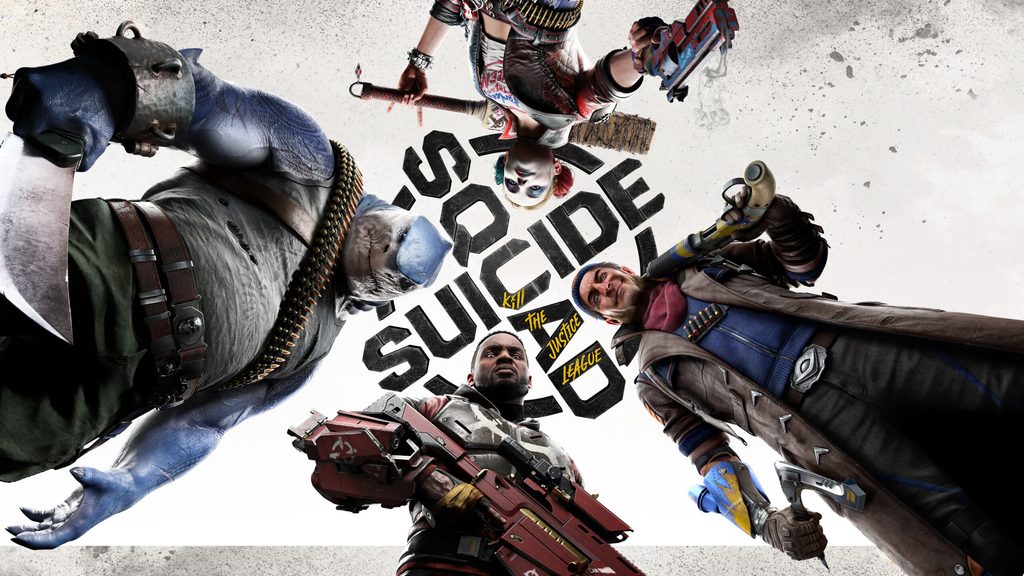

BLOG.PLAYSTATION.COMPlayStation Plus Monthly Games for Jan 2025: Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, Need for Speed Hot Pursuit Remastered, The Stanley Parable: Ultra DeluxeHappy New Year! Kick off your 2025 gaming sessions by taking on (and taking out) a league of corrupted super heroes, race on both sides of the law and escape office life with the PlayStation Plus Monthly Games for January. Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, Need for Speed Hot Pursuit and The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe launch January 7 for PlayStation Plus members*.Lets take a closer look at the games.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageSuicide Squad: Kill the Justice League | PS5Take down The Justice League yourself in single-player or team up with friends in multiplayer co-op in this genre-defying, action-adventure third-person shooter from Rocksteady Studios, creators of the critically acclaimed Batman: Arkham series. Featuring an original narrative set within an expansive open-world city of Metropolis, the game puts the four DC Super-Villains on a collision course with an invading alien force and DC Super Heroes who are now laser-focused on destroying the city they once vowed to protect. All the while, the Suicide Squad must be mindful of the lethal explosives implanted in their heads that could go off at the first sign of defiance. Each squad member has their own unique moveset with enhanced traversal abilities to freely explore the dynamic open-world of Metropolis, along with a variety of weapons to customize, and skills to master.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageNeed for Speed Hot Pursuit Remastered | PS4Feel the thrill of the chase and the rush of escape in Need for Speed Hot Pursuit. Unleash a savage sense of speed both as an outlaw and a cop in the worlds hottest high-performance cars. Outsmart the heat or take down lawbreakers with the tactical weaponry at your disposal in a heart-pumping, socially competitive racing experience. Updated with enhanced visuals, cross-platform multiplayer including the asynchronous competition powered by Autolog plus all additional DLC content, this is the ultimate edition of Criterion Games critically acclaimed Need for Speed debut. Its time to reignite the pursuit.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageThe Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe | PS4, PS5The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe is an expanded re-imagining of the critically acclaimed, award winning indie game The Stanley Parable from 2013. Everything that was in the original Stanley Parable is here, preserved just like it was back in 2013. But The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe also dramatically expands the world of the original game with new content, new choices, and new secrets to uncover. The labyrinth has just gotten bigger. In addition, the game has been visually upgraded to reflect modern technology while faithfully preserving the tone of the original game. Accessibility features have also been added to the game, including localization of in-world text, colorblind options, and content warnings. And just as before, the impeccable voicework of Kevan Brighting will accompany you every step of the way.All three games will be available to PlayStation Plus members on January 7 until February 3.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageLast chance to download Decembers gamesPlayStation Plus members have until January 6 to add It Takes Two, Aliens: Dark Descent and Temtem to their game libraries.*PlayStation Plus Game Catalog lineup may differ in certain regions. Please check the PlayStation Store on launch day for your regions lineup.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились

BLOG.PLAYSTATION.COMPlayStation Plus Monthly Games for Jan 2025: Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, Need for Speed Hot Pursuit Remastered, The Stanley Parable: Ultra DeluxeHappy New Year! Kick off your 2025 gaming sessions by taking on (and taking out) a league of corrupted super heroes, race on both sides of the law and escape office life with the PlayStation Plus Monthly Games for January. Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, Need for Speed Hot Pursuit and The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe launch January 7 for PlayStation Plus members*.Lets take a closer look at the games.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageSuicide Squad: Kill the Justice League | PS5Take down The Justice League yourself in single-player or team up with friends in multiplayer co-op in this genre-defying, action-adventure third-person shooter from Rocksteady Studios, creators of the critically acclaimed Batman: Arkham series. Featuring an original narrative set within an expansive open-world city of Metropolis, the game puts the four DC Super-Villains on a collision course with an invading alien force and DC Super Heroes who are now laser-focused on destroying the city they once vowed to protect. All the while, the Suicide Squad must be mindful of the lethal explosives implanted in their heads that could go off at the first sign of defiance. Each squad member has their own unique moveset with enhanced traversal abilities to freely explore the dynamic open-world of Metropolis, along with a variety of weapons to customize, and skills to master.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageNeed for Speed Hot Pursuit Remastered | PS4Feel the thrill of the chase and the rush of escape in Need for Speed Hot Pursuit. Unleash a savage sense of speed both as an outlaw and a cop in the worlds hottest high-performance cars. Outsmart the heat or take down lawbreakers with the tactical weaponry at your disposal in a heart-pumping, socially competitive racing experience. Updated with enhanced visuals, cross-platform multiplayer including the asynchronous competition powered by Autolog plus all additional DLC content, this is the ultimate edition of Criterion Games critically acclaimed Need for Speed debut. Its time to reignite the pursuit.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageThe Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe | PS4, PS5The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe is an expanded re-imagining of the critically acclaimed, award winning indie game The Stanley Parable from 2013. Everything that was in the original Stanley Parable is here, preserved just like it was back in 2013. But The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe also dramatically expands the world of the original game with new content, new choices, and new secrets to uncover. The labyrinth has just gotten bigger. In addition, the game has been visually upgraded to reflect modern technology while faithfully preserving the tone of the original game. Accessibility features have also been added to the game, including localization of in-world text, colorblind options, and content warnings. And just as before, the impeccable voicework of Kevan Brighting will accompany you every step of the way.All three games will be available to PlayStation Plus members on January 7 until February 3.View and download imageDownload the imagecloseCloseDownload this imageLast chance to download Decembers gamesPlayStation Plus members have until January 6 to add It Takes Two, Aliens: Dark Descent and Temtem to their game libraries.*PlayStation Plus Game Catalog lineup may differ in certain regions. Please check the PlayStation Store on launch day for your regions lineup.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились -

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe most anticipated TTRPG books of 2025Several high-profile tabletop role-playing games that have been in the works for years are scheduled to finally be released in 2025, setting the stage for a year where players and game masters will truly be spoiled for choice. As Wizards of the Coast finishes its 50th-anniversary rules refresh with the release of a new Monster Manual, it will face competition from former collaborators, including Critical Roles Darrington Press, Paizo, and MCDM, as the fallout from Hasbros attempted revisions to the Open Gaming License continues years after the plan was abandoned.Even still, D&Ds pull remains powerful. While Wizards publication schedule is relatively light in 2025, with a long gap between the Monster Manual and an as-yet-unnamed adventure anthology being released in the summer, third-party publishers continue to find creative new spins on the system. This year will offer 5th edition players the chance to hunt kaiju and delve into folk horror. Other new releases offer the opportunity to tell new stories in the worlds of two of the most beloved fantasy authors. Whatever youre looking for in a TTRPG, this alphabetical list offers a glimpse of the books were most excited about.The Broken Empires RPGTrevor Devall is publishing the gritty fantasy setting and skill-based system he developed over the course of four seasons of actual plays on the TTRPG channel Me, Myself and Die!, picking and choosing mechanics from more than 125 other games. The Broken Empires RPG promises to prioritize exploration and intrigue while offering a high level of flexibility for characters.Cosmere RPGBrandon Sanderson isnt planning on returning to the Stormlight Archive for six years, but fans of the epic fantasy series will be able to have their own adventures on Roshar with the Cosmere RPG. The author worked closely with Brotherwise Games to develop a system that will begin there with an adventure that ties directly into his latest book, but the game promises to grow to include campaigns in Sandersons Mistborn setting and the possibility of stories that move between worlds.The Crooked MoonOriginally expected for release in 2024, The Crooked Moon was delayed until 2025 so that Legends of Avantris could deliver a product worthy of its ambitions and its $4 million Kickstarter campaign. The folk horror setting for Dungeons & Dragons 5e promises terrifying adventures, epic multiphase boss fights, and twisted curses, while offering players plenty of spooky new species and subclass options.Critical Roles DaggerheartCritical Role helped inspire a new generation of Dungeons & Dragons players, but now its Darrington Press imprint is launching its own high fantasy RPG. While some early players think its not distinct enough, the Daggerheart open beta has hooked others with innovations like card-based character creation and tracking both emotional stress and hit points. Swapping the d20 for 2d12s also allows for more consistent player abilities, avoiding the frustration of missing too often.Draw Steel (formerly the MCDM RPG)MCDM has made plenty of excellent supplements for D&D 5e, like Flee, Mortals! and Strongholds & Followers, but like so many third-party publishers the company was shaken by the OGL fiasco. It has spent the intervening time developing its own system, Draw Steel, that will focus on dynamic action, keeping combats moving quickly by lumping attack and damage into a single roll and granting characters resources as they fight so that combats get more intense as the rounds pass.Monster ManualWizards of the Coast will complete the revision of the D&D 5e core rulebooks in February with the release of its largest-ever Monster Manual. The book will feature more than 90 brand-new monsters along with hundreds of favorites that have been redesigned and rebalanced. It also promises to make things easier on DMs with a more intuitive organization system. The updated Dungeon Masters Guide and Players Handbook have helped push the 50-year-old game forward, and hopefully its refreshed dragons and owlbears will do the same.Pathfinder Lost Omens: Rival AcademiesFans of magical school stories and anyone looking for inspiration for their next Pathfinder monk or wizard will want to pick up Pathfinder Lost Omens: Rival Academies when it comes out in March. Paizo has been doing a great job at enriching its already complex setting with its Lost Omens series, and this promises to be a particularly fun entry, set at a gathering of six academies each with their own specialty, from mad science to exploring the fae realms.Ryokos Guide to the Yokai RealmsThe highly anticipated follow-up to Loot Taverns D&D 5e book Helianas Guide to Monster Hunting, Ryokos Guide to the Yokai Realms takes the publishers dynamic crafting system and penchant for engaging boss fights into a setting inspired by East Asian mythology and pop culture. Players will be able to hunt kaiju and learn how to exploit their vulnerabilities, play a new class based on Avatar: The Last Airbender, and coordinate with their party members to unleash combo attacks.Starfinder Second Edition Player CoreThe playtest for Starfinder 2e already feels like a huge achievement, thanks to its depth of character options and monsters, creative changes to the world, and rich initial adventures, but its really designed to get feedback from players and game masters that will shape the Gen Con release of the Starfinder Second Edition Player Core and the books that come after. The science fantasy games rules have been made fully compatible with Pathfinder 2e, making it easier for gaming groups to try their hand at planet hopping and dealing with everything from political intrigue to cosmic horrors. You can still find the playtest materials right now, free to download online.Terry Pratchetts Discworld RPG: Adventures in Ankh-MorporkModiphius Entertainment has a great track record of high-profile TTRPG adaptations, including Dune: Adventures in the Imperium and Fallout: The Roleplaying Game, and its applying it to the irreverent world of Terry Pratchetts beloved fantasy series in Terry Pratchetts Discworld RPG: Adventures in Ankh-Morpork. Rather than using Modiphius signature 2d20 mechanics, the game employs a custom Narrativium system, keeping the mechanics simple so you can focus on making puns.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe most anticipated TTRPG books of 2025Several high-profile tabletop role-playing games that have been in the works for years are scheduled to finally be released in 2025, setting the stage for a year where players and game masters will truly be spoiled for choice. As Wizards of the Coast finishes its 50th-anniversary rules refresh with the release of a new Monster Manual, it will face competition from former collaborators, including Critical Roles Darrington Press, Paizo, and MCDM, as the fallout from Hasbros attempted revisions to the Open Gaming License continues years after the plan was abandoned.Even still, D&Ds pull remains powerful. While Wizards publication schedule is relatively light in 2025, with a long gap between the Monster Manual and an as-yet-unnamed adventure anthology being released in the summer, third-party publishers continue to find creative new spins on the system. This year will offer 5th edition players the chance to hunt kaiju and delve into folk horror. Other new releases offer the opportunity to tell new stories in the worlds of two of the most beloved fantasy authors. Whatever youre looking for in a TTRPG, this alphabetical list offers a glimpse of the books were most excited about.The Broken Empires RPGTrevor Devall is publishing the gritty fantasy setting and skill-based system he developed over the course of four seasons of actual plays on the TTRPG channel Me, Myself and Die!, picking and choosing mechanics from more than 125 other games. The Broken Empires RPG promises to prioritize exploration and intrigue while offering a high level of flexibility for characters.Cosmere RPGBrandon Sanderson isnt planning on returning to the Stormlight Archive for six years, but fans of the epic fantasy series will be able to have their own adventures on Roshar with the Cosmere RPG. The author worked closely with Brotherwise Games to develop a system that will begin there with an adventure that ties directly into his latest book, but the game promises to grow to include campaigns in Sandersons Mistborn setting and the possibility of stories that move between worlds.The Crooked MoonOriginally expected for release in 2024, The Crooked Moon was delayed until 2025 so that Legends of Avantris could deliver a product worthy of its ambitions and its $4 million Kickstarter campaign. The folk horror setting for Dungeons & Dragons 5e promises terrifying adventures, epic multiphase boss fights, and twisted curses, while offering players plenty of spooky new species and subclass options.Critical Roles DaggerheartCritical Role helped inspire a new generation of Dungeons & Dragons players, but now its Darrington Press imprint is launching its own high fantasy RPG. While some early players think its not distinct enough, the Daggerheart open beta has hooked others with innovations like card-based character creation and tracking both emotional stress and hit points. Swapping the d20 for 2d12s also allows for more consistent player abilities, avoiding the frustration of missing too often.Draw Steel (formerly the MCDM RPG)MCDM has made plenty of excellent supplements for D&D 5e, like Flee, Mortals! and Strongholds & Followers, but like so many third-party publishers the company was shaken by the OGL fiasco. It has spent the intervening time developing its own system, Draw Steel, that will focus on dynamic action, keeping combats moving quickly by lumping attack and damage into a single roll and granting characters resources as they fight so that combats get more intense as the rounds pass.Monster ManualWizards of the Coast will complete the revision of the D&D 5e core rulebooks in February with the release of its largest-ever Monster Manual. The book will feature more than 90 brand-new monsters along with hundreds of favorites that have been redesigned and rebalanced. It also promises to make things easier on DMs with a more intuitive organization system. The updated Dungeon Masters Guide and Players Handbook have helped push the 50-year-old game forward, and hopefully its refreshed dragons and owlbears will do the same.Pathfinder Lost Omens: Rival AcademiesFans of magical school stories and anyone looking for inspiration for their next Pathfinder monk or wizard will want to pick up Pathfinder Lost Omens: Rival Academies when it comes out in March. Paizo has been doing a great job at enriching its already complex setting with its Lost Omens series, and this promises to be a particularly fun entry, set at a gathering of six academies each with their own specialty, from mad science to exploring the fae realms.Ryokos Guide to the Yokai RealmsThe highly anticipated follow-up to Loot Taverns D&D 5e book Helianas Guide to Monster Hunting, Ryokos Guide to the Yokai Realms takes the publishers dynamic crafting system and penchant for engaging boss fights into a setting inspired by East Asian mythology and pop culture. Players will be able to hunt kaiju and learn how to exploit their vulnerabilities, play a new class based on Avatar: The Last Airbender, and coordinate with their party members to unleash combo attacks.Starfinder Second Edition Player CoreThe playtest for Starfinder 2e already feels like a huge achievement, thanks to its depth of character options and monsters, creative changes to the world, and rich initial adventures, but its really designed to get feedback from players and game masters that will shape the Gen Con release of the Starfinder Second Edition Player Core and the books that come after. The science fantasy games rules have been made fully compatible with Pathfinder 2e, making it easier for gaming groups to try their hand at planet hopping and dealing with everything from political intrigue to cosmic horrors. You can still find the playtest materials right now, free to download online.Terry Pratchetts Discworld RPG: Adventures in Ankh-MorporkModiphius Entertainment has a great track record of high-profile TTRPG adaptations, including Dune: Adventures in the Imperium and Fallout: The Roleplaying Game, and its applying it to the irreverent world of Terry Pratchetts beloved fantasy series in Terry Pratchetts Discworld RPG: Adventures in Ankh-Morpork. Rather than using Modiphius signature 2d20 mechanics, the game employs a custom Narrativium system, keeping the mechanics simple so you can focus on making puns.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились -

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe 44 most exciting science fiction and fantasy books for your 2025 reading listIts that time of the year again! As we finally put 2024 to bed, its time to start looking forward to what the 2025 publishing season holds in store for our TBR piles. The answer, at a glance, is a lot. Seriously, the time to reinforce all of your bookshelves so that they do not collapse in on themselves is now, my friends. 2025 marks a hotly anticipated, and no doubt emotionally devastating, return to Panem that will reflect the state of the world in the way Suzanne Collins does best; a new vampire novel from modern master of the horror genre Stephen Graham Jones; and a little spicy romantasy from the minds of Critical Role with a little help from Thea Guanzon. Needless to say, theres a little something for everyone!The following are 44 books you can look forward to in 2025.Daughter of Chaos (The Dark Pantheon #1) by A.S. WebbJan. 14Set in ancient Greece on the island of Naxos, Daughter of Chaos by A.S. Webb tells the story of Danae, a fishermans daughter who discovers that she has mysterious powers. Cast out from her home and determined to find the truth of who she is, Danae joins forces with Heracles and his monster-fighting comrades.Fans of Greek mythology might already know that Danae is the mother of Perseus, but Daughter of Chaos is a reimagining of the myth, which begs the question of what exactly lies in store for the hero of Webbs new series.Helen of Troy, 1993: Poems by Maria ZoccolaJan. 14Speaking of Greek mythologyIts difficult to put into words how gorgeous and apropos of the world we live in Maria Zoccolas debut collection of poetry, Helen of Troy, 1993, is, but Ill try my best.This sparkling, feminist collection of work reimagines Helen from Homers Iliad as a housewife in Sparta, Tennessee, in the early 1990s. Its a clever mashup of mythology and modernity that feels akin to Maria Dahvana Headleys recent translation of Beowulf. Everything old is new again, and in this case it creates a snapshot of the rural South and a powerful, unapologetic woman who is the object of desire no matter when or where the story is told.Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady HendrixJan. 14If youre a horror fan like me, then its hard not to love Grady Hendrix. Hes written about everything from selling haunted houses to exorcisms to vampire-fighting book clubs, and in his new book, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls, hes tackling the occult.Set in the 1970s at a Floridian institution where young pregnant women can have their babies in secret so as not to shame their families, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls tells the story of 15-year-old Fern and the girls she befriends there. While their day-to-day lives are strictly monitored, Fern discovers an unexpected source of untapped power and, potentially, an escape when shes given a book of occult witchcraft by a librarian.Motheater by Linda H. CodegaJan. 21Set in the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia, Linda H. Codegas debut novel is an atmospheric, queer fantasy that pits nature and industry against one another.After the sudden death of her best friend, Bennie Mattox gives up everything in order to try and find out what exactly has been killing the miners up on Kire Mountain. The last thing she expects to find is a half-drowned woman who claims to be a witch who is bound to protect Kire from the seemingly inevitable progress of industry. But the more time they spend together, the more Bennie feels drawn to the mysterious Motheater and the future they could build together.Blob: A Love Story by Maggie SuJan. 28When Vi Liu, the daughter of a Taiwanese father and white mother, goes to a drag show with her friend Rachel, she discovers an amorphous, sentient blob with beady black eyes. Vi decides to take the blob home with her and, before long, she realizes that she can shape her new companion into whatever she wants, including a perfect boyfriend. The result is Glen Powell-esque and, while undeniably handsome, her new blobby boyfriend forces Vi on a journey of self-discovery that is as delightful and touching as it is downright strange.The Lamb by Lucy RoseFeb. 4Billed as being for fans of Angela Carter and Julia Armfield (a deadly combination if ever Ive seen one), The Lamb by Lucy Rose is a modern fairy tale and gothic coming-of-age.Margot has lived with her mama by the edge of the forest for as long as she can remember. Her mama likes to take in strays, people who have wandered too far from the road, and looks after them for a time. But when a gorgeous stray by the name of Eden arrives, the relationship between Margot and her mother begins to change drastically as she navigates her own needs and wants.Anoxia by Miguel ngel Hernndez (translated by Adrian Nathan West)Feb. 4Set 10 years after the sudden death of her husband, Anoxia tells the story of Dolores Ayala, a photographer who receives an unusual request from a man by the name of Clemente Arts. Clemente is obsessed with the tradition of photographing the dead on the day of their funeral, and begins to train Dolores in this practice. What unravels is a nuanced ghost story in which the lines between the living and the dead become increasingly blurred.Victorian Psycho by Virginia FeitoFeb. 4From Virgina Feito, author of Mrs. March, comes a gothic, dark comedy that is already being made into a movie starring Margaret Qualley and Thomasin McKenzie about a governess hell-bent on giving the staff something to talk about.On paper, Winifred Notty is an absolutely perfect governess. Thats why the Pounds family has hired her. But the more time Winifred spends with her charges, Drusilla and Andrew, the more she begins to learn about the Pounds and their strange habits, and the more she begins to give in to her own odd compulsions.Listen to Your Sister by Neena VielFeb. 4Stranger Things by way of Jordan Peele, Listen to Your Sister, by debut novelist Neena Viel, promises to be as much a terrifying fever dream as it is a laugh-out-loud comedy.After becoming the guardian of her younger brother, Jamie, Calla Williams has begun suffering from hyperrealistic, violent dreams in which he dies before she can save him. When his actions at a protest get Jamie in a little too much trouble, the two hightail it to a remote Airbnb to try and wait out the chaos. But Callas nightmare continues to haunt her, bringing a new threat to their well-being to light.The Crimson Road by A.G. SlatterFeb. 11A.G. Slatter, author of All the Murmuring Bones, The Path of Thorns, and The Briar Book of the Dead returns once again to her Sourdough Universe with the latest in the series, The Crimson Road.Violet Zennor has trained all of her life to be skilled in hand-to-hand combat thanks to her father, Hederek. When her father dies, Violet thinks she might finally be free of the hell that he has put her through.But freedom comes at a price, and her father has debts to be paid and a mess to be cleaned up. Ultimately Violet must venture into the Darklands and the Anchorhold beyond, meeting some familiar faces along the way.Beta Vulgaris by Margie SarsfieldFeb. 11Who knew that vegetables could be so scary?Determined to find a way to pay for her Brooklyn apartment, Elise and her boyfriend, Tom, pick up a summer job in Minnesota helping to harvest sugar beets (aka Beta vulgaris). But what should be an easy gig quickly takes a turn when the grueling labor begins to run Elise into the ground and she discovers a strange, unexplainable rash on her body. Worse still is the disembodied voice that seems to be coming from the pile of harvested beets itself.The Spirit Collection of Thorne Hall by J. Ann ThomasFeb. 11The year is 1890, and it is Elegy Thornes job to keep the spirits that occupy Thorne Hall, her familys grand estate in the Berkshires, at peace. When one of the spirits causes a small bit of chaos within her home, a local preservationist and his son are called upon for assistance. The last thing Elegy expects is to find herself torn between Thorne family tradition and the spirits she has known her whole life, and a young man who dreams of modernity.But Not Too Bold by Hache PueyoFeb. 11Hache Pueyos upcoming novella, But Not Too Bold, is for all of my fellow monster lovers out there.The best way to describe Anatema, the Lady of the Capricious House, is somewhere between Lady Dimitrescu from Resident Evil Village and The Will from Saga. She is, essentially, a humanoid spider-woman with a weakness and insatiable hunger for beautiful women. Enter Dlia, the newest keeper of the keys for Capricious House. What Dlia doesnt know is that her mistress ate her predecessor, and that she might be next on the menu if shes not careful.Emily Wildes Compendium of Lost Tales by Heather FawcettFeb. 11If you havent been keeping up with Emily Wilde and her escapades, then youre missing out on one of the most romantic and heartwarming fantasy series to hit shelves in years.In this new installment, Emily faces her most dangerous challenge yet: researching faerie folk and their realm as their new queen. Now that shes engaged to Wendell, her frustratingly handsome academic rival/princely cohort turned fianc, this should, hypothetically, be easy to accomplish. But Wendells bloodthirsty stepmother has other plans in mind, and not everyone is so willing to have an academic, let alone a human, as their new ruler.Upon a Starlit Tide by Kell WoodsFeb. 18What do you get when you mix The Little Mermaid and Cinderella? The answer is Upon a Starlit Tide by Kell Woods.The year is 1758, and Lucinde Leon dreams of escaping the walled city of Saint-Malo, where she is the youngest daughter of a wealthy sea captain. Lucinde spends her days learning to sail with her best friend, Samuel, but her secret afternoons on the water soon change when she rescues Morgan de Chatelaine, the son of a wealthy ship owner, from drowning.Hungerstone by Kat DunnFeb. 18As is the case with all good vampire stories, the push and pull between fear and desire in Kat Dunns new novel, Hungerstone, is palpable from its very first pages.After 10 years together, the relationship between Lenore and her husband, Henry, has taken a turn for the worse. When Henry decides to host a hunt at the remote and foreboding Nethershaw Manor, Lenore reluctantly accompanies him. But when a fluke carriage accident brings the mysterious Carmilla (yes, that Carmilla) suspiciously weak during the day and full of vigor at night into her life, Lenore finds herself inexplicably drawn to her new acquaintance.Fagin the Thief by Allison EpsteinFeb. 25Historical fiction fans, rejoice! Allison Epstein is back, and this time with a novel that focuses on one of Londons most gifted thieves.Fans of Charles Dickens will recognize the name Jacob Fagin right away. He is, of course, the infamous and, dare I say, fan-favorite pickpocket from Oliver Twist. In Epsteins new novel, she puts Fagin at the forefront, reimagining Dickens work through the eyes of a Jewish man looking to make a name for himself on the streets of London in the wake of his fathers death.Greenteeth by Molly ONeillFeb. 25If youre anything like me, and familiar with English folklore, then you might recognize the name Jenny Greenteeth. Shes typically depicted as a river hag who would pull unsuspecting victims into the water, but Molly ONeills Greenteeth is a little bit different. Sure, she still has needle-like teeth and lives underwater, but when a witch by the name of Temperance is thrown into her lake, she has a change of heart. Though theyre nothing alike, Jenny and Temperance become unlikely allies as they join forces to defeat the evil that plagues their home.The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (translated by Sarah Moses)March 4Fans of religious horror (and Tender Is the Flesh) will want to put Agustina Bazterricas new novel, The Unworthy, at the top of their TBR list ASAP.Told by a nameless woman, sequestered in a mysterious convent known as the House of the Sacred Sisterhood as the world falls apart, The Unworthy is a mashup of dystopian climate crisis and violent extremism. When a stranger breaches the convents walls, it throws everyone for a loop, and Bazterricas narrator soon finds herself questioning what enlightenment really means and what it takes to get there.They Bloom at Night by Trang Thanh TranMarch 4I have been a fan of Trang Thanh Tran since their debut horror novel, She Is a Haunting, and have been waiting with bated breath for their second book ever since.They Bloom at Night tells the story of Noon, a young woman whose hometown of Mercy, Louisiana, has been overtaken by a red algae bloom after a devastating hurricane. To make matters more complicated, Noons mother believes that their family are sea creatures. With another storm looming on the horizon and Mercys leader breathing down Noons neck, its a race against time to find out if her mother is right or something more sinister is afoot.The River Has Roots by Amal El-MohtarMarch 4Best known for her deeply romantic novel, This Is How You Lose the Time War (co-written with Max Gladstone), Amal El-Mohtars new novella brings readers to the far-off town of Thistleford. Thistleford is the home of the strange and mysterious Hawthorne family, who spend their days harvesting willows. Sisters Esther and Ysabel are as dedicated to this task as they are to one another, but when Esther chooses love over propriety, it tests the bonds of sisterhood.Fan Service by Rosie DananMarch 11If youre looking for a book to fill the Teen Wolf-shaped hole in your heart, then look no further than Rosie Danans new romance novel, Fan Service.In her youth, Alex Lawson ran an online forum for a show about the supernatural called The Arcane Files. She also had a big fat crush on the shows star, Devin Ashwood, before he proved himself to be a real jerk. Now, years later, Devin is beginning to show the symptoms of being a werewolf, not unlike those his character suffered from, and Ash, now a small-town vet, might be the only person who can help him.The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham JonesMarch 18Horror legend Stephen Graham Jones is headed back in time for his highly anticipated new novel, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter.Set in the American West during 1912, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter follows the story of a Lutheran priest transcribing the life of a vampire member of the Blackfeet tribe, hell-bent on revenge after the death of 217 tribe members.Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne CollinsMarch 18March 2025 marks a return to Panem for Suzanne Collins, this time for another Quarter Quell and a young Haymitch Abernathy just before his name is called for the infamous Hunger Games. Theres no doubt in my mind that Collins will break fans hearts as we learn about the events that will eventually make him the man who takes Katniss under his wing.Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert by Bob the Drag QueenMarch 25Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert is, hands down, one of my most anticipated books of 2025 for a couple of reasons.The first, of course, is that it is written by Bob the Drag Queen, winner of RuPauls Drag Race and creator of Were Here, which is nothing short of spectacular. The second reason is that Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert reimagines the American hero as a wannabe Broadway star determined to make a different name for herself while still honoring her history with the help of a hip-hop producer she meets along the way. Its a wild and utterly original concept for a book that will, no doubt, be a chart topper in and of itself.Sour Cherry by Natalia TheodoridouApril 1Sour Cherry by Natalia Theodoridou is a fairy tale within a fairy tale, at once a retelling of Bluebeard and something wholly original and really gorgeous about everything from toxic masculinity to a mothers love. Theodoridou gives a voice to the victims in her novel that is as tragic as it is poignant.Gifted & Talented by Olivie BlakeApril 1If you watched Succession and found yourself wishing there was a little more magic involved, Gifted & Talented might be just the book for you.Thayer Wren, CEO of Wrenfare Magitech, is dead. Its common knowledge that any one of his brilliant, telepathically and electrokinetically skilled children could be the one to inherit the family business. The only question is who it might be, and what exactly theyre willing to do in order to inheritthe mantle.Cold Eternity by S.A. BarnesApril 8Ive been a fan of S.A. Barnes since her first space horror novel and personally cannot wait to get my hands on a copy of Cold Eternity.On the run from a political scandal, a woman by the name of Halley finds a brief bit of respite on a space barge hosting the cryogenically frozen bodies of earths most elite citizens. The ship has long been out of use and while Halley knows, logically, that shes the only conscious human being on board, that doesnt change the fact that shes starting to see figures in the hallways.Sky Daddy by Kate FolkApril 8Sky Daddy is far and away one of the most audacious and surprisingly feel-good books that 2025 has to offer.Linda has a secret. She is sexually attracted to airplanes (yes, really) and indulges herself by taking a round trip flight from SFO to a random regional hub. In fact, she believes that its her destiny to marry one of her Boeing suitors by dying in a plane crash. But a chance lunch date with a work friend changes all that as Lindas carefully balanced life, and secret desires, begin to spiral out of control.Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng by Kylie Lee BakerApril 29Hold on to your hat. Bat Eater is a wild ride from start to finish, an intense examination of the racism toward Chinese people (especially in the wake of COVID-19), and, quite possibly, one of the best horror novels of early 2025.As a crime scene cleaner in New York Citys Chinatown during COVID, its safe to say that Cora Zeng does not have an easy job. That said, the grisly remains that she deals with are nothing compared to the memory of watching her sister be pushed in front of a train. While the murderer was never caught, what he shouted as he fled the scene has stuck with Cora ever since: Bat Eater. While she struggles to differentiate between whats real and whats in her head, Cora cant shake the feeling that there must be some sort of connection between the bat carcasses she keeps finding at crime scenes, the fact that all of her recent jobs have involved the bodies of East Asian women, and her sisters murder.When the Tides Held the Moon by Venessa Vida KelleyApril 29Part historical fiction, part epic queer romance, part fairy tale, and part illustrated novel, When the Tides Held the Moon is quite unlike anything else on this list.Set at the turn of the 20th century in New York City, When the Tides Held the Moon tells the story of Benigno Benny Caldera, an orphan known for the ironwork tank he made for Coney Island. The last thing Benny expected was for his tank to be used for a living, breathing merman or to find himself falling in love with him.Traitor of Sherwood Forest By Amy S. KaufmanApril 29I am a big sucker for a reimagining of Robin Hood and, as such, am incredibly excited to get my hands on a copy of The Traitor of Sherwood Forest by Amy S. Kaufman.This reimagining in particular is told through the eyes of Jane Crowe, a peasant girl turned spy for the infamous thief himself. The more time Jane spends with the charismatic rebel, the more she feels herself drawn to him, but when his uprising grows increasingly chaotic and violent, Jane begins to wonder if the Lord of the Greenwood is all hes cracked up to be.Polybius by Collin ArmstrongApril 29Based on a popular urban legend born from the idea of the American government using video games for psychological warfare, Collin Armstrongs new novel is a wild ride from beginning to end.The year is 1982 and Andi and her mother have just moved to the picturesque, boring town of Tasker Bay. When Polybius, a hot new video game, shows up at the local arcade, Andi and her new (and only) friend, Ro, decide to go check it out. But when people who have played the game start to become paranoid and uncontrollably violent, Andi cant shake the feeling that there might be a connection between this mystery virus and the new video game.Bochica by Carolina Flrez-CerchiaroMay 13Who doesnt love a book about a haunted house?In Bochica, a young woman by the name of Antonia and her family move into La Casona, a deeply haunted estate located in Soacha, Colombia. Its so haunted, in fact, its causing Antonias entire family to suffer from horrendous nightmares. Three years after a fatal accident took her mothers life and her father attempted to burn the house down in a fit of grief, Antonia returns to her childhood home, now a hotel, to look for answers about what really happened that fateful night.Of Monsters and Mainframes by Barbara TrueloveMay 13Somewhere between pulp horror and classic sci-fi youll find Barbara Trueloves upcoming, totally punk-rock queer space odyssey, Of Monsters and Mainframes.Demeter is a spaceship struggling to transport her human cargo from Earth to Alpha Centauri. They keep inconveniently dying and, in order to keep from being decommissioned, Demeter needs that to stop. Demeter believes that these arent just your run-of-the-mill human deaths, though. These are supernatural occurrences and, in order to put them to an end, shell have to team up with a vampire, a werewolf, and an undead engineer to close the case as quickly as possible.Anji Kills a King (The Rising Tide #1) by Evan LeikamMay 13For those who also loved The Blacktongue Thief and The Daughters War and have been looking to scratch that itch ever since, Anji Kills a King by Evan Leikam promises to do just that.Its no spoiler to say that Anji Kills a King begins with Anji killing a king. Now, with her life in shambles, a bounty on her head, and some of the kingdoms most skilled mercenaries hot on her heels, Anji has to keep moving to stay alive. But when the Hawk, a veteran swordswoman, finally catches up, an unlikely alliance forms between the two women.The Country Under Heaven by Frederic S. DurbinMay 13What would happen if you dropped Arthur Morgan in the middle of an H.P. Lovecraft story? The answer might just be Frederic S. Durbins fantasy Western novel, The Country Under Heaven.Ovid Vesper, a union soldier who has been plagued by enigmatic visions after surviving the Battle of Antietam, has set across the American West to look for answers. Why him? What do the visions mean? The closer he gets to answering these questions, the stranger the world around him seems to become.Metallic Realms by Lincoln MichelMay 13I am a big ol fan of Lincoln Michel. So much so, in fact, that I think hes one of the sharpest and cleverest minds when it comes to modern sci-fi, and his latest work, Metallic Realms, is further proof of that fact. Its also a wonderful ode to being a nerd.The lead character in Metallic Realms, Michael Lincoln, is, in fact, just that: a big nerd. And while he didnt grow up to be like the sci-fi heroes of his youth, he is taking it upon himself to do something heroic. He is determined to preserve The Star Rot Chronicles, a series written by his best friend, Taras K. Castle, and their writing group, Orb 4, and it just so happens to include the greatest multiverse ever created.This Princess Kills Monsters: The Misadventures of a Fairy-Tale Stepsister by Ry HermanJune 17In This Princess Kills Monsters, its clear that someone wants Princess Melilot dead. Worse still is the fact that her stepmother wont stop sending her on dangerous quests that always seem to end with her being rescued by her stepsisters, and the fact that shes being forced to marry a king shes never met. When one quest in particular ends with her being rescued by a group of masked huntsmen rather than her sisters, Melilot comes to the conclusion that she might be the only one with the skills needed to stop whats happening to her.Tusk Love by Thea Guanzon and Critical RoleJuly 1The cast of Critical Role has said it time and time again: The world could use more smutty fantasy novels in it. And theyre taking it upon themselves to give us exactly that.Written by Thea Guanzon, author of The Hurricane Wars, Tusk Love tells the story of Guinevere, a merchants daughter who longs for adventure, and Oskar, the half-orc bandit who she meets during an attack on the caravan shes traveling with. Fans of Critical Role, and Jester and Fjord in particular, will be familiar with the layers to this romantic story, but its a delightful (and spicy) tale for those who are just getting their foot in the D&D door as well.One Yellow Eye by Leigh RadfordJuly 15If youre in the mood to read a literary zombie novel (with an excellent cover), look no further than Leigh Radfords new book, One Yellow Eye.Kestas husband is dead. Well, undead, technically, and tied up in her bedroom, as he was one of the last to be bitten during a zombie pandemic. A scientist by day, Kesta is determined to find a cure for the disease that is ravaging her husbands body before shes found out, or worse, another outbreak occurs.The Hounding by Xenobe PurvisAug. 5Following in Nightbitchs footsteps and continuing the tradition of novels in which a woman or, in this case, women might be turning into a dog, is The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis.The villagers living in the town of Little Nettlebed have never much liked the Mansfield girls. And while the belief in witchcraft was waning in England during the 18th century, they cant help but feel that theres something not quite right about them. When the villagers begin to hear barking, and one sees one of the girls turn into a dog before their very eyes, it becomes clear to them that something entirely supernatural is afoot.Love at First Sighting by Mallory MarloweAug. 12I was a huge fan of Mallory Marlowes first romance novel, Love and Other Conspiracies, and Love at First Sighting sounds like itll be every bit as delightful.Social media influencer El Martin wants to believe. In love, that is. The last thing she expects is for her heart to be all aflutter over footage of a mysterious flying aircraft, let alone Agent Carter Brody, the Private Intelligence Sector officer assigned to her. Carter himself is thrown by Els confidence, and the veracity of her footage, and soon enough the two are on the hunt to find out whether little green men are real or not.The Possession of Alba Daz by Isabel CaasAug. 19I would be lying if I said that I havent been feverishly counting down the days until Isabel Caas next book hits shelves.In her new novel, a plague is ravaging the town of Zacatecas. In order to save themselves, Alba and her husband, Carlos, take shelter in an abandoned mine. But, as time passes, Alba begins to experience strange hallucinations, and the encroaching feeling that she is not alone. Enter Elias, who cant help but notice the chemistry between himself and Alba whenever she enters the room. The problem, of course, is that Alba is married to his cousin and, very possibly, being possessed by a demon.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились

WWW.POLYGON.COMThe 44 most exciting science fiction and fantasy books for your 2025 reading listIts that time of the year again! As we finally put 2024 to bed, its time to start looking forward to what the 2025 publishing season holds in store for our TBR piles. The answer, at a glance, is a lot. Seriously, the time to reinforce all of your bookshelves so that they do not collapse in on themselves is now, my friends. 2025 marks a hotly anticipated, and no doubt emotionally devastating, return to Panem that will reflect the state of the world in the way Suzanne Collins does best; a new vampire novel from modern master of the horror genre Stephen Graham Jones; and a little spicy romantasy from the minds of Critical Role with a little help from Thea Guanzon. Needless to say, theres a little something for everyone!The following are 44 books you can look forward to in 2025.Daughter of Chaos (The Dark Pantheon #1) by A.S. WebbJan. 14Set in ancient Greece on the island of Naxos, Daughter of Chaos by A.S. Webb tells the story of Danae, a fishermans daughter who discovers that she has mysterious powers. Cast out from her home and determined to find the truth of who she is, Danae joins forces with Heracles and his monster-fighting comrades.Fans of Greek mythology might already know that Danae is the mother of Perseus, but Daughter of Chaos is a reimagining of the myth, which begs the question of what exactly lies in store for the hero of Webbs new series.Helen of Troy, 1993: Poems by Maria ZoccolaJan. 14Speaking of Greek mythologyIts difficult to put into words how gorgeous and apropos of the world we live in Maria Zoccolas debut collection of poetry, Helen of Troy, 1993, is, but Ill try my best.This sparkling, feminist collection of work reimagines Helen from Homers Iliad as a housewife in Sparta, Tennessee, in the early 1990s. Its a clever mashup of mythology and modernity that feels akin to Maria Dahvana Headleys recent translation of Beowulf. Everything old is new again, and in this case it creates a snapshot of the rural South and a powerful, unapologetic woman who is the object of desire no matter when or where the story is told.Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady HendrixJan. 14If youre a horror fan like me, then its hard not to love Grady Hendrix. Hes written about everything from selling haunted houses to exorcisms to vampire-fighting book clubs, and in his new book, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls, hes tackling the occult.Set in the 1970s at a Floridian institution where young pregnant women can have their babies in secret so as not to shame their families, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls tells the story of 15-year-old Fern and the girls she befriends there. While their day-to-day lives are strictly monitored, Fern discovers an unexpected source of untapped power and, potentially, an escape when shes given a book of occult witchcraft by a librarian.Motheater by Linda H. CodegaJan. 21Set in the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia, Linda H. Codegas debut novel is an atmospheric, queer fantasy that pits nature and industry against one another.After the sudden death of her best friend, Bennie Mattox gives up everything in order to try and find out what exactly has been killing the miners up on Kire Mountain. The last thing she expects to find is a half-drowned woman who claims to be a witch who is bound to protect Kire from the seemingly inevitable progress of industry. But the more time they spend together, the more Bennie feels drawn to the mysterious Motheater and the future they could build together.Blob: A Love Story by Maggie SuJan. 28When Vi Liu, the daughter of a Taiwanese father and white mother, goes to a drag show with her friend Rachel, she discovers an amorphous, sentient blob with beady black eyes. Vi decides to take the blob home with her and, before long, she realizes that she can shape her new companion into whatever she wants, including a perfect boyfriend. The result is Glen Powell-esque and, while undeniably handsome, her new blobby boyfriend forces Vi on a journey of self-discovery that is as delightful and touching as it is downright strange.The Lamb by Lucy RoseFeb. 4Billed as being for fans of Angela Carter and Julia Armfield (a deadly combination if ever Ive seen one), The Lamb by Lucy Rose is a modern fairy tale and gothic coming-of-age.Margot has lived with her mama by the edge of the forest for as long as she can remember. Her mama likes to take in strays, people who have wandered too far from the road, and looks after them for a time. But when a gorgeous stray by the name of Eden arrives, the relationship between Margot and her mother begins to change drastically as she navigates her own needs and wants.Anoxia by Miguel ngel Hernndez (translated by Adrian Nathan West)Feb. 4Set 10 years after the sudden death of her husband, Anoxia tells the story of Dolores Ayala, a photographer who receives an unusual request from a man by the name of Clemente Arts. Clemente is obsessed with the tradition of photographing the dead on the day of their funeral, and begins to train Dolores in this practice. What unravels is a nuanced ghost story in which the lines between the living and the dead become increasingly blurred.Victorian Psycho by Virginia FeitoFeb. 4From Virgina Feito, author of Mrs. March, comes a gothic, dark comedy that is already being made into a movie starring Margaret Qualley and Thomasin McKenzie about a governess hell-bent on giving the staff something to talk about.On paper, Winifred Notty is an absolutely perfect governess. Thats why the Pounds family has hired her. But the more time Winifred spends with her charges, Drusilla and Andrew, the more she begins to learn about the Pounds and their strange habits, and the more she begins to give in to her own odd compulsions.Listen to Your Sister by Neena VielFeb. 4Stranger Things by way of Jordan Peele, Listen to Your Sister, by debut novelist Neena Viel, promises to be as much a terrifying fever dream as it is a laugh-out-loud comedy.After becoming the guardian of her younger brother, Jamie, Calla Williams has begun suffering from hyperrealistic, violent dreams in which he dies before she can save him. When his actions at a protest get Jamie in a little too much trouble, the two hightail it to a remote Airbnb to try and wait out the chaos. But Callas nightmare continues to haunt her, bringing a new threat to their well-being to light.The Crimson Road by A.G. SlatterFeb. 11A.G. Slatter, author of All the Murmuring Bones, The Path of Thorns, and The Briar Book of the Dead returns once again to her Sourdough Universe with the latest in the series, The Crimson Road.Violet Zennor has trained all of her life to be skilled in hand-to-hand combat thanks to her father, Hederek. When her father dies, Violet thinks she might finally be free of the hell that he has put her through.But freedom comes at a price, and her father has debts to be paid and a mess to be cleaned up. Ultimately Violet must venture into the Darklands and the Anchorhold beyond, meeting some familiar faces along the way.Beta Vulgaris by Margie SarsfieldFeb. 11Who knew that vegetables could be so scary?Determined to find a way to pay for her Brooklyn apartment, Elise and her boyfriend, Tom, pick up a summer job in Minnesota helping to harvest sugar beets (aka Beta vulgaris). But what should be an easy gig quickly takes a turn when the grueling labor begins to run Elise into the ground and she discovers a strange, unexplainable rash on her body. Worse still is the disembodied voice that seems to be coming from the pile of harvested beets itself.The Spirit Collection of Thorne Hall by J. Ann ThomasFeb. 11The year is 1890, and it is Elegy Thornes job to keep the spirits that occupy Thorne Hall, her familys grand estate in the Berkshires, at peace. When one of the spirits causes a small bit of chaos within her home, a local preservationist and his son are called upon for assistance. The last thing Elegy expects is to find herself torn between Thorne family tradition and the spirits she has known her whole life, and a young man who dreams of modernity.But Not Too Bold by Hache PueyoFeb. 11Hache Pueyos upcoming novella, But Not Too Bold, is for all of my fellow monster lovers out there.The best way to describe Anatema, the Lady of the Capricious House, is somewhere between Lady Dimitrescu from Resident Evil Village and The Will from Saga. She is, essentially, a humanoid spider-woman with a weakness and insatiable hunger for beautiful women. Enter Dlia, the newest keeper of the keys for Capricious House. What Dlia doesnt know is that her mistress ate her predecessor, and that she might be next on the menu if shes not careful.Emily Wildes Compendium of Lost Tales by Heather FawcettFeb. 11If you havent been keeping up with Emily Wilde and her escapades, then youre missing out on one of the most romantic and heartwarming fantasy series to hit shelves in years.In this new installment, Emily faces her most dangerous challenge yet: researching faerie folk and their realm as their new queen. Now that shes engaged to Wendell, her frustratingly handsome academic rival/princely cohort turned fianc, this should, hypothetically, be easy to accomplish. But Wendells bloodthirsty stepmother has other plans in mind, and not everyone is so willing to have an academic, let alone a human, as their new ruler.Upon a Starlit Tide by Kell WoodsFeb. 18What do you get when you mix The Little Mermaid and Cinderella? The answer is Upon a Starlit Tide by Kell Woods.The year is 1758, and Lucinde Leon dreams of escaping the walled city of Saint-Malo, where she is the youngest daughter of a wealthy sea captain. Lucinde spends her days learning to sail with her best friend, Samuel, but her secret afternoons on the water soon change when she rescues Morgan de Chatelaine, the son of a wealthy ship owner, from drowning.Hungerstone by Kat DunnFeb. 18As is the case with all good vampire stories, the push and pull between fear and desire in Kat Dunns new novel, Hungerstone, is palpable from its very first pages.After 10 years together, the relationship between Lenore and her husband, Henry, has taken a turn for the worse. When Henry decides to host a hunt at the remote and foreboding Nethershaw Manor, Lenore reluctantly accompanies him. But when a fluke carriage accident brings the mysterious Carmilla (yes, that Carmilla) suspiciously weak during the day and full of vigor at night into her life, Lenore finds herself inexplicably drawn to her new acquaintance.Fagin the Thief by Allison EpsteinFeb. 25Historical fiction fans, rejoice! Allison Epstein is back, and this time with a novel that focuses on one of Londons most gifted thieves.Fans of Charles Dickens will recognize the name Jacob Fagin right away. He is, of course, the infamous and, dare I say, fan-favorite pickpocket from Oliver Twist. In Epsteins new novel, she puts Fagin at the forefront, reimagining Dickens work through the eyes of a Jewish man looking to make a name for himself on the streets of London in the wake of his fathers death.Greenteeth by Molly ONeillFeb. 25If youre anything like me, and familiar with English folklore, then you might recognize the name Jenny Greenteeth. Shes typically depicted as a river hag who would pull unsuspecting victims into the water, but Molly ONeills Greenteeth is a little bit different. Sure, she still has needle-like teeth and lives underwater, but when a witch by the name of Temperance is thrown into her lake, she has a change of heart. Though theyre nothing alike, Jenny and Temperance become unlikely allies as they join forces to defeat the evil that plagues their home.The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (translated by Sarah Moses)March 4Fans of religious horror (and Tender Is the Flesh) will want to put Agustina Bazterricas new novel, The Unworthy, at the top of their TBR list ASAP.Told by a nameless woman, sequestered in a mysterious convent known as the House of the Sacred Sisterhood as the world falls apart, The Unworthy is a mashup of dystopian climate crisis and violent extremism. When a stranger breaches the convents walls, it throws everyone for a loop, and Bazterricas narrator soon finds herself questioning what enlightenment really means and what it takes to get there.They Bloom at Night by Trang Thanh TranMarch 4I have been a fan of Trang Thanh Tran since their debut horror novel, She Is a Haunting, and have been waiting with bated breath for their second book ever since.They Bloom at Night tells the story of Noon, a young woman whose hometown of Mercy, Louisiana, has been overtaken by a red algae bloom after a devastating hurricane. To make matters more complicated, Noons mother believes that their family are sea creatures. With another storm looming on the horizon and Mercys leader breathing down Noons neck, its a race against time to find out if her mother is right or something more sinister is afoot.The River Has Roots by Amal El-MohtarMarch 4Best known for her deeply romantic novel, This Is How You Lose the Time War (co-written with Max Gladstone), Amal El-Mohtars new novella brings readers to the far-off town of Thistleford. Thistleford is the home of the strange and mysterious Hawthorne family, who spend their days harvesting willows. Sisters Esther and Ysabel are as dedicated to this task as they are to one another, but when Esther chooses love over propriety, it tests the bonds of sisterhood.Fan Service by Rosie DananMarch 11If youre looking for a book to fill the Teen Wolf-shaped hole in your heart, then look no further than Rosie Danans new romance novel, Fan Service.In her youth, Alex Lawson ran an online forum for a show about the supernatural called The Arcane Files. She also had a big fat crush on the shows star, Devin Ashwood, before he proved himself to be a real jerk. Now, years later, Devin is beginning to show the symptoms of being a werewolf, not unlike those his character suffered from, and Ash, now a small-town vet, might be the only person who can help him.The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham JonesMarch 18Horror legend Stephen Graham Jones is headed back in time for his highly anticipated new novel, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter.Set in the American West during 1912, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter follows the story of a Lutheran priest transcribing the life of a vampire member of the Blackfeet tribe, hell-bent on revenge after the death of 217 tribe members.Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne CollinsMarch 18March 2025 marks a return to Panem for Suzanne Collins, this time for another Quarter Quell and a young Haymitch Abernathy just before his name is called for the infamous Hunger Games. Theres no doubt in my mind that Collins will break fans hearts as we learn about the events that will eventually make him the man who takes Katniss under his wing.Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert by Bob the Drag QueenMarch 25Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert is, hands down, one of my most anticipated books of 2025 for a couple of reasons.The first, of course, is that it is written by Bob the Drag Queen, winner of RuPauls Drag Race and creator of Were Here, which is nothing short of spectacular. The second reason is that Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert reimagines the American hero as a wannabe Broadway star determined to make a different name for herself while still honoring her history with the help of a hip-hop producer she meets along the way. Its a wild and utterly original concept for a book that will, no doubt, be a chart topper in and of itself.Sour Cherry by Natalia TheodoridouApril 1Sour Cherry by Natalia Theodoridou is a fairy tale within a fairy tale, at once a retelling of Bluebeard and something wholly original and really gorgeous about everything from toxic masculinity to a mothers love. Theodoridou gives a voice to the victims in her novel that is as tragic as it is poignant.Gifted & Talented by Olivie BlakeApril 1If you watched Succession and found yourself wishing there was a little more magic involved, Gifted & Talented might be just the book for you.Thayer Wren, CEO of Wrenfare Magitech, is dead. Its common knowledge that any one of his brilliant, telepathically and electrokinetically skilled children could be the one to inherit the family business. The only question is who it might be, and what exactly theyre willing to do in order to inheritthe mantle.Cold Eternity by S.A. BarnesApril 8Ive been a fan of S.A. Barnes since her first space horror novel and personally cannot wait to get my hands on a copy of Cold Eternity.On the run from a political scandal, a woman by the name of Halley finds a brief bit of respite on a space barge hosting the cryogenically frozen bodies of earths most elite citizens. The ship has long been out of use and while Halley knows, logically, that shes the only conscious human being on board, that doesnt change the fact that shes starting to see figures in the hallways.Sky Daddy by Kate FolkApril 8Sky Daddy is far and away one of the most audacious and surprisingly feel-good books that 2025 has to offer.Linda has a secret. She is sexually attracted to airplanes (yes, really) and indulges herself by taking a round trip flight from SFO to a random regional hub. In fact, she believes that its her destiny to marry one of her Boeing suitors by dying in a plane crash. But a chance lunch date with a work friend changes all that as Lindas carefully balanced life, and secret desires, begin to spiral out of control.Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng by Kylie Lee BakerApril 29Hold on to your hat. Bat Eater is a wild ride from start to finish, an intense examination of the racism toward Chinese people (especially in the wake of COVID-19), and, quite possibly, one of the best horror novels of early 2025.As a crime scene cleaner in New York Citys Chinatown during COVID, its safe to say that Cora Zeng does not have an easy job. That said, the grisly remains that she deals with are nothing compared to the memory of watching her sister be pushed in front of a train. While the murderer was never caught, what he shouted as he fled the scene has stuck with Cora ever since: Bat Eater. While she struggles to differentiate between whats real and whats in her head, Cora cant shake the feeling that there must be some sort of connection between the bat carcasses she keeps finding at crime scenes, the fact that all of her recent jobs have involved the bodies of East Asian women, and her sisters murder.When the Tides Held the Moon by Venessa Vida KelleyApril 29Part historical fiction, part epic queer romance, part fairy tale, and part illustrated novel, When the Tides Held the Moon is quite unlike anything else on this list.Set at the turn of the 20th century in New York City, When the Tides Held the Moon tells the story of Benigno Benny Caldera, an orphan known for the ironwork tank he made for Coney Island. The last thing Benny expected was for his tank to be used for a living, breathing merman or to find himself falling in love with him.Traitor of Sherwood Forest By Amy S. KaufmanApril 29I am a big sucker for a reimagining of Robin Hood and, as such, am incredibly excited to get my hands on a copy of The Traitor of Sherwood Forest by Amy S. Kaufman.This reimagining in particular is told through the eyes of Jane Crowe, a peasant girl turned spy for the infamous thief himself. The more time Jane spends with the charismatic rebel, the more she feels herself drawn to him, but when his uprising grows increasingly chaotic and violent, Jane begins to wonder if the Lord of the Greenwood is all hes cracked up to be.Polybius by Collin ArmstrongApril 29Based on a popular urban legend born from the idea of the American government using video games for psychological warfare, Collin Armstrongs new novel is a wild ride from beginning to end.The year is 1982 and Andi and her mother have just moved to the picturesque, boring town of Tasker Bay. When Polybius, a hot new video game, shows up at the local arcade, Andi and her new (and only) friend, Ro, decide to go check it out. But when people who have played the game start to become paranoid and uncontrollably violent, Andi cant shake the feeling that there might be a connection between this mystery virus and the new video game.Bochica by Carolina Flrez-CerchiaroMay 13Who doesnt love a book about a haunted house?In Bochica, a young woman by the name of Antonia and her family move into La Casona, a deeply haunted estate located in Soacha, Colombia. Its so haunted, in fact, its causing Antonias entire family to suffer from horrendous nightmares. Three years after a fatal accident took her mothers life and her father attempted to burn the house down in a fit of grief, Antonia returns to her childhood home, now a hotel, to look for answers about what really happened that fateful night.Of Monsters and Mainframes by Barbara TrueloveMay 13Somewhere between pulp horror and classic sci-fi youll find Barbara Trueloves upcoming, totally punk-rock queer space odyssey, Of Monsters and Mainframes.Demeter is a spaceship struggling to transport her human cargo from Earth to Alpha Centauri. They keep inconveniently dying and, in order to keep from being decommissioned, Demeter needs that to stop. Demeter believes that these arent just your run-of-the-mill human deaths, though. These are supernatural occurrences and, in order to put them to an end, shell have to team up with a vampire, a werewolf, and an undead engineer to close the case as quickly as possible.Anji Kills a King (The Rising Tide #1) by Evan LeikamMay 13For those who also loved The Blacktongue Thief and The Daughters War and have been looking to scratch that itch ever since, Anji Kills a King by Evan Leikam promises to do just that.Its no spoiler to say that Anji Kills a King begins with Anji killing a king. Now, with her life in shambles, a bounty on her head, and some of the kingdoms most skilled mercenaries hot on her heels, Anji has to keep moving to stay alive. But when the Hawk, a veteran swordswoman, finally catches up, an unlikely alliance forms between the two women.The Country Under Heaven by Frederic S. DurbinMay 13What would happen if you dropped Arthur Morgan in the middle of an H.P. Lovecraft story? The answer might just be Frederic S. Durbins fantasy Western novel, The Country Under Heaven.Ovid Vesper, a union soldier who has been plagued by enigmatic visions after surviving the Battle of Antietam, has set across the American West to look for answers. Why him? What do the visions mean? The closer he gets to answering these questions, the stranger the world around him seems to become.Metallic Realms by Lincoln MichelMay 13I am a big ol fan of Lincoln Michel. So much so, in fact, that I think hes one of the sharpest and cleverest minds when it comes to modern sci-fi, and his latest work, Metallic Realms, is further proof of that fact. Its also a wonderful ode to being a nerd.The lead character in Metallic Realms, Michael Lincoln, is, in fact, just that: a big nerd. And while he didnt grow up to be like the sci-fi heroes of his youth, he is taking it upon himself to do something heroic. He is determined to preserve The Star Rot Chronicles, a series written by his best friend, Taras K. Castle, and their writing group, Orb 4, and it just so happens to include the greatest multiverse ever created.This Princess Kills Monsters: The Misadventures of a Fairy-Tale Stepsister by Ry HermanJune 17In This Princess Kills Monsters, its clear that someone wants Princess Melilot dead. Worse still is the fact that her stepmother wont stop sending her on dangerous quests that always seem to end with her being rescued by her stepsisters, and the fact that shes being forced to marry a king shes never met. When one quest in particular ends with her being rescued by a group of masked huntsmen rather than her sisters, Melilot comes to the conclusion that she might be the only one with the skills needed to stop whats happening to her.Tusk Love by Thea Guanzon and Critical RoleJuly 1The cast of Critical Role has said it time and time again: The world could use more smutty fantasy novels in it. And theyre taking it upon themselves to give us exactly that.Written by Thea Guanzon, author of The Hurricane Wars, Tusk Love tells the story of Guinevere, a merchants daughter who longs for adventure, and Oskar, the half-orc bandit who she meets during an attack on the caravan shes traveling with. Fans of Critical Role, and Jester and Fjord in particular, will be familiar with the layers to this romantic story, but its a delightful (and spicy) tale for those who are just getting their foot in the D&D door as well.One Yellow Eye by Leigh RadfordJuly 15If youre in the mood to read a literary zombie novel (with an excellent cover), look no further than Leigh Radfords new book, One Yellow Eye.Kestas husband is dead. Well, undead, technically, and tied up in her bedroom, as he was one of the last to be bitten during a zombie pandemic. A scientist by day, Kesta is determined to find a cure for the disease that is ravaging her husbands body before shes found out, or worse, another outbreak occurs.The Hounding by Xenobe PurvisAug. 5Following in Nightbitchs footsteps and continuing the tradition of novels in which a woman or, in this case, women might be turning into a dog, is The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis.The villagers living in the town of Little Nettlebed have never much liked the Mansfield girls. And while the belief in witchcraft was waning in England during the 18th century, they cant help but feel that theres something not quite right about them. When the villagers begin to hear barking, and one sees one of the girls turn into a dog before their very eyes, it becomes clear to them that something entirely supernatural is afoot.Love at First Sighting by Mallory MarloweAug. 12I was a huge fan of Mallory Marlowes first romance novel, Love and Other Conspiracies, and Love at First Sighting sounds like itll be every bit as delightful.Social media influencer El Martin wants to believe. In love, that is. The last thing she expects is for her heart to be all aflutter over footage of a mysterious flying aircraft, let alone Agent Carter Brody, the Private Intelligence Sector officer assigned to her. Carter himself is thrown by Els confidence, and the veracity of her footage, and soon enough the two are on the hunt to find out whether little green men are real or not.The Possession of Alba Daz by Isabel CaasAug. 19I would be lying if I said that I havent been feverishly counting down the days until Isabel Caas next book hits shelves.In her new novel, a plague is ravaging the town of Zacatecas. In order to save themselves, Alba and her husband, Carlos, take shelter in an abandoned mine. But, as time passes, Alba begins to experience strange hallucinations, and the encroaching feeling that she is not alone. Enter Elias, who cant help but notice the chemistry between himself and Alba whenever she enters the room. The problem, of course, is that Alba is married to his cousin and, very possibly, being possessed by a demon.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились -

WWW.POLYGON.COMWhen is Squid Game coming to Black Ops 6?Netflixs Squid Game is making an appearance in Black Ops 6.The crossover with the hit series will add new limited-time modes, operators, and weapon blueprints to the game in 2025. Surprisingly, the show is not only coming to multiplayer, but to Zombies and Warzone as well. Be on your toes and look out for any suspicious people playing ddakji or offering you a choice between bread and scratch-offs. That is, unless you wish to participate yourself.Heres when Squid Game is releasing in Black Ops 6, and what we do and dont know about the collaboration so far.When is Squid Game coming to Black Ops 6?Squid Game is coming to Black Ops 6 on Friday, Jan. 3, according to the Call of Duty X account.An official release time has not been announced, but Black Ops 6 updates usually occur between the hours of 9 11 a.m. PST. Heres when that is in your time zone:9-11 a.m. PST for the West Coast of North America12-2 p.m. EST for the East Coast of North America5-7 p.m. GMT for the U.K.6-8 p.m. CET for Western Europe/Paris2-4 a.m. JST on Jan. 4 for Tokyo4-6 a.m AEDT on Jan. 4 for the East Coast of AustraliaWhat to expect in the Squid Game collabWhat we know about the Squid Game collab so farNew limited time modes added to multiplayer, Zombies, and Warzone in-season according to a Call of Duty blog post. In the collaboration trailer, there appears to be a Red Light, Green Light game that takes place on Red Card, and ddakjis may have replaced dog tags in Kill Confirmed. The trailer also shows that Red Light, Green Light will make an appearance in Warzone as the animatronic girl guards a few chests.New operators dressed in iconic Squid Game fashion have been confirmed. Play as the one of the workers, the Front Man, a VIP, Players 115 and 006, and even the robot girl from Red Light, Green Light. New weapon blueprints are coming as well and a few can be seen in the collaboration trailer. There arent many iconic weapons from the series, so these could be the MP5s that the workers are holding or entirely new skins.What we dont know about the Squid Game collab so farWere not sure what the limited time modes will entail, but the trailer does seem to showcase Red Light, Green Light across multiplayer and Warzone. As for Zombies, VIPs are watching from the balconies and theyre thrilled to see you take on the horde, but that is all we know about Zombies so far.How long the collaboration will last. Black Ops 6 season 1 is expected to end on Jan. 28, 2025, and the Squid Game collab is listed as one of the Season 1 Reloaded events, so we can assume that the collab will end either before the 28th or on the same day.0 Комментарии 0 Поделились