Stand Up for Science Must March On to Mean Anything

www.scientificamerican.com

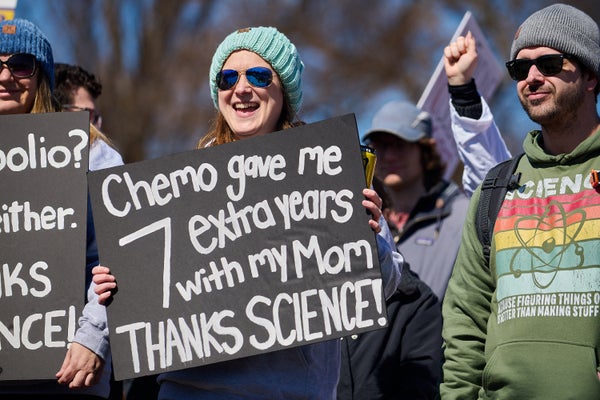

OpinionMarch 11, 20255 min readA Science Protest Offers Insight into the Science of ProtestingStand Up for Science shows how science supporters are coming togetherBy Dan Vergano edited by Jeanna BrynerThousands protest the Trump administration's federal funding cuts during the Stand-Up for Science rally in Washington D.C., Friday, March 7, 2025. Dominic Gwinn/Middle East Images via AFPWASHINGTON, D.C.The crowd streamed down from subways and sidewalks to the Lincoln Memorial, carrying signs on a bright, chilly day.It marched for science. During the March 7 Stand Up for Science protest in Washington, D.C., one of many nationwide, including in Chicago, Philadelphia and other U.S. and overseas cities, the crowd rallied to defend science as a public good and pillar of social, political, and economic progress, according to the organizers policy goals. Whether the gathering at the Lincoln Memorial represented the start of a bigger movement or a mere gesture in a nation turning its back on science hung in the air, undecided, as the songs and speeches began.The crowd brandished signs that were equal parts nerdy, clever and full of outrage. Speakers ranging from former National Institutes of Health chief Francis Collins to TV icon Bill Nye (and even astronomer Phil Plait, who writes a column for Scientific American) spoke to the crowd, which consisted of a few thousand people on that Friday afternoon. They condemned the mass firings, extreme budget cuts and shuttered safety panels that have been the result of actions undertaken at federal agencies since January by the Trump administration and its chainsaw-brandishing vizier Elon Musk. We have a job to do, said Atul Gawande, author, surgeon and former assistant administrator of global health at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). We must bear witness to the truth. We must bear witness to the damage.On supporting science journalismIf you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.Yet the most important people at the protest may not have been on the stage but in the audience. People like Sara Rouhi, who works in research publishing and is a co-author of the Declaration to Defend Research against U.S. Government Censorship, steadily traversed the crowd, QR-coded sign and shirt at the ready.Were trying to organize people across the board to push back, said Rouhi, who added that the group behind the declaration has signed up 3,000 supporters so far. Its looking to combine forces with organizations like the Union of Concerned Scientists, she said, as well as the Data Rescue Projects effort to collect and curate U.S. government data erased from public view by the Trump administration.A protestor at the 'Stand for Science' event in Washington D.C.Dan VerganoThat kind of activism, mobilizing people to act, is the real business at a protest, says American University sociologist Dana Fisher, author of American Resistance: From the Womens March to the Blue Wave. The big point of protests is to channel outrage into something else, Fisher said. Give people a sense of identity and engagement thats longer-term and more embedded in a movement than just showing up and holding a sign, right?Whether the protest marks the start of an effective resistance to Trumps moves starts with the crowd, then, not the speakers. It was refreshing, though, to hear Collinsso politically adroit during his tenure as NIH chief that he mostly avoided pandemic-related nonsense from Trumpcriticize pharmaceutical companies for not speaking out against moves to slash research spending. (Collins, a guitarist, also played a science-tinged version of the folk song All the Good People as the crowd sang along.)In the U.S., protests have shifted substantially since the 1970s. Decades ago massive organizing preceded massive protests. Without social media, people werent centrally connected, so local groups needed to decide to organize together and march on Washington, D.C. Everything from renting buses to signing people up for those seats took work that formed the glue that connected activists and culminated in the protest.Nowadays its really very different. Protest becomes the beginning of a movement rather than the end, says Fisher, who added that social media speeds organizing. The Womens March in 2017, for examplethe largest single-day protest in U.S. historywas a harbinger of a blue wave election a year later that gave the Democrats control of the U.S. House of Representatives. That march channeled the outrage that many people felt over Trumps behavior in his first term in office and turned it into activism and engagement that led to the highest midterm voter turnout since 1914.Theres a right way and a wrong way to do protests, especially protests as a form of resistance, Fisher said. The 2018 March for Our Lives, organized by students after 17 people were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., that year, brought hundreds of thousands of people to hundreds of events that often featured celebrities and bands. But while it led to record youth voter registrations and played a role in the short-lived ban on rifle bump stocks (overturned last year by the U.S. Supreme Court in a fit of gun-fetishizing bunkum), any bigger movement to end gun violence is on its back foot in the Trump era. In the 2024 U.S. election, younger mens voting shifted to Trump even though they came of age in the March for Our Lives era of school lockdowns and continued mass shootings, such as the 2022 murder of 19 schoolchildren and two teachers in Uvalde, Tex.Scientists and their supporters now face a similar test. In its first weeks, the Trump administration has targeted the U.S. scientific enterprise broadly, the culmination of decades of attacks on climate scientists, safety panels and health officials by business-backed politicians like Trump.Its personal this time, says Fisher, who is no longer able to fund one researcher that she had supported because of the recent cuts and still funds three others with federal grants. I work with a number of colleagues who believe they are on lists, who may be fired. Her team surveyed the protest and found that it was a first protest for about 22 percent of participants. It was also a highly educated crowd; 37 percent of people reported that they had a Ph.D., M.D. or J.D. Only in Washington, D.C.Today Stand Up for Science stands at a crossroads. Organized mainly by graduate students, the protests could mark a wider start of scientific resistance to the authoritarian offensive, as Harvard University political scientist Steven Levitsky described the actions of the new Trump administration in an Intelligencer interview. But thats only if people in the crowd do more than hold signs and sing songs. They should join local community groups or advocacy groups, Fisher said, or a data-recovery effort like the Data Rescue Project. Even organizing a book club is a good thing, she says. Only if the people protesting organize and draw in more people to effectively resist Trumps moves will all the signs and singing matter. They are off to a good start: 45 percent of people sampled by Fisher and her colleagues said that they had contacted an elected official in the last year.Rouhi said she is just getting started. This cant be the end, she said of the protests. If its the end, its end for all of us.This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

0 Comments

·0 Shares

·38 Views