www.architectural-review.com

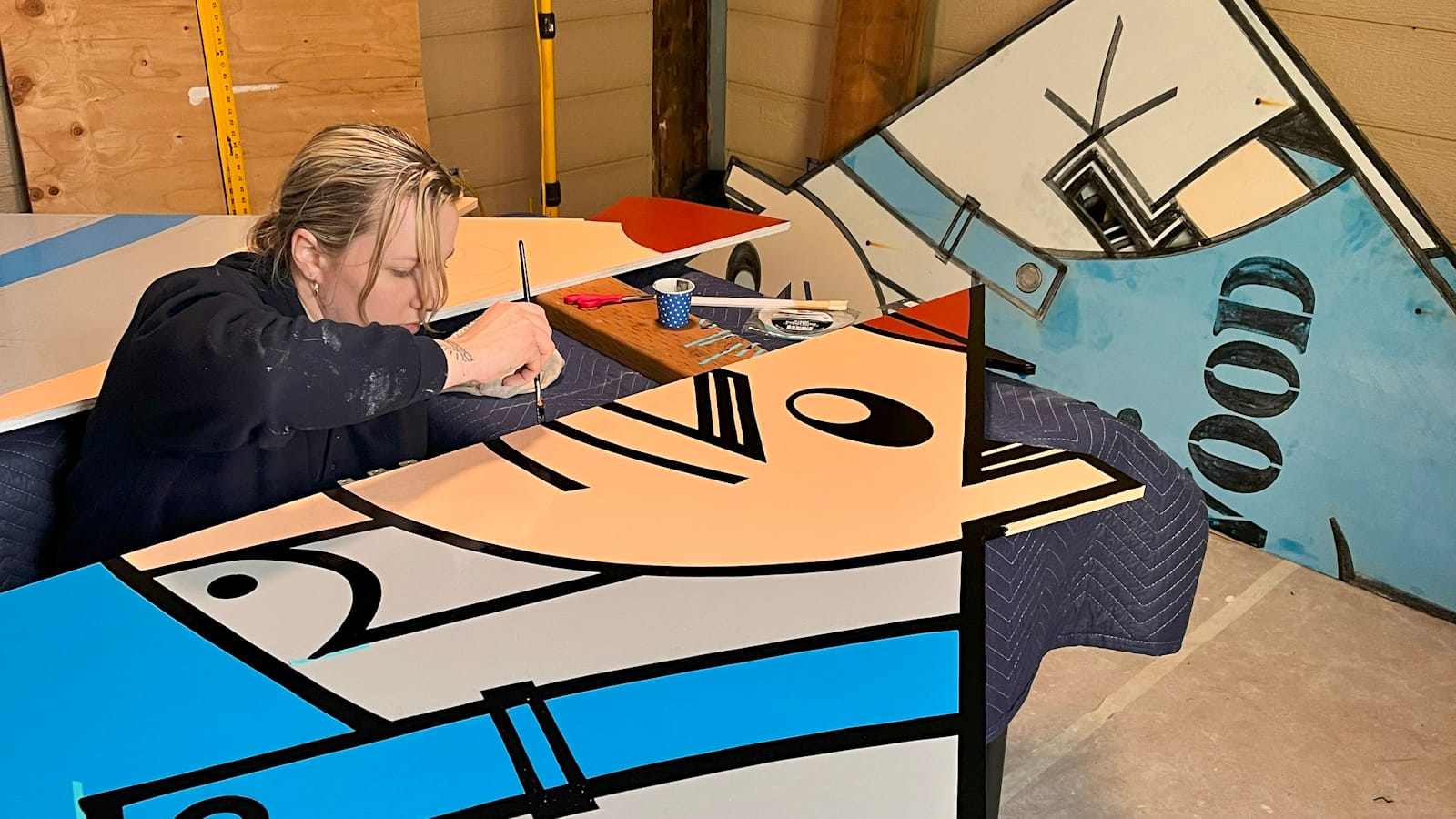

The Arklow wastewater treatment plant in Ireland, designed by Clancy Moore, is an act of public serviceThe Irish Sea near the town of Arklow was once home to 90km ofnaturally occurring oyster reefs. During the 19th century, Arklow was the countrys main port for oysters 40million were harvested in 1863, with many exported to England, the colonial metropole. But by the end of the 1800s, the oyster beds were depleting due to overharvesting and pollution from the Avoca mines upstream; even in the 1860s, oysters were rebedded elsewhere to remove the taste of copper, dispensed into the river by the mines, beforebeing sold.Since the 19th century, the water qualityof the Avoca River and the sea into whichitdischarges has suffered, due to bothindustry and a lack of wastewater infrastructure. Until June 2024, when the new Arklow wastewater treatment plant began operation, raw sewage as well as greywater and surface runoff was released directly into the river. The lower reaches ofthe Avoca River constituted the most polluted stretches of river in Ireland, according to a 2003 Eastern Regional Fisheries Board report. In 2019, the European Court of Justice took Ireland tocourt for its failure to treat wastewater inArklow, along with 37 other Irish towns.Attempts to build a wastewater treatment plant began in the 1990s but were frustrated by searches for a suitable site. In 2016, alocation was selected at the mouth oftheAvoca River, next to the marina andprominently visible from the town tothesouth. We came to the conclusion that if were going to build something there, it needs to be a civic building that were proud of and that speaks to the town, explains Michael Tinsley, an engineer and senior manager at Uisce ireann (formerly Irish Water), who commissioned the project. Weneed to get an architect involved here. There was an invited competition in 2016 for a practice to join the existing design team, led by Arup and Ayesa Engineering. Dublinbased practice Clancy Moore were anunlikely addition to the lineup, invited on the commendation of a planner who hadbeen impressed by a house on a sensitive quarry site which the practice had designed in 2008.The lower reaches of the Avoca River constituted the most polluted stretches of river in IrelandClancy Moore found themselves aconsultant among many; around 20 specialisms were represented in the design team (odour engineerarticularly niche favourite). In the built project, however, thearchitects hand is keenly felt. From a distance, the monumental louvred volumes appear almost toylike, emerging from between tanks and warehouses like oversized pleated origami. This is how thebuildings will be experienced by most people: a landmark viewed across the river from the south quay or glimpsed on a windy walk by the sea to the north. As Andrew Clancy, cofounder of Clancy Moore, explains, while not accessible to the public,the project is fundamentally for andabout the public good.Clancy Moore have achieved more than just smart dresses for giant sheds. In one ofmany meetings, the architects casually asked if it was possible to put this on that, marking a departure from typical sewage plant design, in which processes are arrayed horizontally and tanks are sunk into the ground. At Arklow, the initial treatment processes where grit and nonorganic objects, such as wet wipes and nappies, areremoved take place on an upper level, with large storm tanks and skips for collecting the removed material below. Wastewater ispumped up to the raised level from the underground sewer and then flows by gravity to the second volume which contains aeration tanks effectively giant petri dishes where bacteria break down harmful compounds before making the journey down a kilometrelong outfall pipe to the Irish Sea.This decision to stack processes precipitated a chain reaction of happy consequences. Volumes were able to be morevertical: confident urban figures with acivic presence. The only evidence that the buildings are in fact part of a sewage works will be a lorry coming out a couple of times aweek to take dried sludge away to eitherbe used as fertiliser or incinerated togenerate electricity. The volumes had to have roofs because the higher areas needed to be served by gantry cranes, which in turn meant that solar panels could be installed onthe roofs (currently just one roof but there are plans to roll out on the second inacouple of years). These will be able to contribute up to40 per cent of the plants energy demands reduced compared with typical arrangements, where wastewater ispumped between each tank rather than fed by gravity. The reduced built area alsoallowed a third of the site area toberewilded, including plants that willhelp todecontaminate the ground.The giant louvres, like halfclosed Venetian blinds, allow air circulation without revealing the unsavoury innards, and are already welcoming small birds looking for a nesting spot (though netting prevents wildlife from venturing further inside). The fins of corrugated fibrecement board, the colour of oxidised copper, hang from a steelframed carapace, the steel columns meeting the ground on hefty concrete feet, a precaution against manoeuvring trucks. The small office building at the site entrance speaks the same language as its two larger siblings butin a softer register, with concrete wedges supporting a portico that echoes the louvres, gently lapped cementboard cladding in the same marine green, and windows in a dance along each facade, like notes on a stave.The reference here to John Hejduks Kreuzberg Tower in Berlin is wittily rehearsed (the facade at the entrance resembles I suspect intentionally a face in profile), and the two louvred sheds heavily quote Hans Christian Hansens Amager switching stations in Copenhagen: large warehouselike buildings with corrugated louvres that flap up and down to allow ventilation. Clancy Moores project itself hasalso been quoted; before the wastewater plant was even completed, DMOD Architects headquarters for Arklow Shipping was builtin 2022 with an oversizedgreen sawtooth roof.Concrete was a prerequisite for the tanks and other processes, for which no other material is suitable, and a steel frame was selected due to structural demands and the exposed marine location. The choice of fibrecement cladding emerged following countless iterative studies: a cast in situ concrete facade was vaunted as there was plenty more concrete already being poured on site, and timber options were considered, though it unfolded that withstanding the tough conditions would require slowgrowth oak and copper nails. This was unsurprisingly quickly dismissed. A hardier, more industrial palette was selected; the corrugated cement board rhymes with thesurrounding industrial sheds, still usedfor shipbuilding.One resident welled up as she noticed that the frothy scum that had habitually laced the edges of the river had disappearedThe Arklow wastewater treatment plantisa rare example of a sewage works designed by an architect, and one of, if not the first in Ireland. The project wastendered as part of a design and build engineering contract that did not include a single drawing. Instead, the architects drew through writing, in a document of over 60 pages, meticulously describing the basis of the buildings: from the plans (a foursided structure, rectangular in plan) down to thedetails (there are to be no horizontal joints between fibrecement panels). Thedocument proves, in case there were anydoubt, that a drawing is worth several thousand words.This is a project of conversation between professionals from innumerable disciplines, and with planning authorities and local people. Clancy and cofounder Colm Moore see the practice as stewards or guardians of the project, navigating and negotiating between the various specialist expertises placed on the table, rather than leading theproject. They also proved to be crucial advocates of the project in consultations with the public: The architects had them sitting down and within five minutes, they were nodding about how the project would speak to the marine history of Arklow, Tinsley describes. Very early on we saw thebenefit of having the architects involved.Tinsley also notes that there has been very little resistance to the project from the local community perhaps expected given the previous dire situation, though unusual asnot everyone wants a sewage plant as aneighbour. Any qualms that the public might have about frivolous spending of taxpayers money on aesthetics can be quelled by Tinsleys estimates that only around 3 per cent of the projects budget was spent on the architecture a small price to pay for a civic landmark.This is a socially and ecologically transformative piece of infrastructure. Onanopen day shortly after the plant beganoperations last year, one resident welled up as she noticed that the frothy scum that had habitually laced the edges of the river had disappeared. But perhaps the most dramatic transformation that will result from the operation of the plant will beurban growth, suppressed since the late 1990s on the grounds that there wasnt adequate wastewater treatment provision the population of the town has hovered around 13,000 for the last 15 years. The new wastewater treatment plant is the key that will unlock development: the plant has the capacity to allow the town to nearly triple insize, with two tanks currently dormant. Asingle development of 476 units on agreenfield site to the south of the town wasgranted planning permission in December 2024.But the towns population had been suppressed since long before the 1990s. The population of the Republic of Ireland only recently, in 2022, surpassed five million for the first time since 1851, just recovering after centuries of English then British colonisation, including a genocidal famine. As Clancy points out, the population growth in Arklow will not be an explosion, but areturn to the normal population dynamics ofthe country as a whole. He hopes young people may now choose to stay and that a considered approach will be taken to urban development. One small positive from the failure to build a plant before is that Arklow was spared the substandard developments of the boom, and of the last 10 years.The deprivation caused by British colonisation and economic mismanagement since independence in 1922 has resulted in underdeveloped infrastructure, including wastewater. In 2014, 50 Irish towns were without water treatment; Arklow was the 35th on the todo list (six more are set to receive treatment plants this year, and thelast nine are at planning stage). The stateowned water company Uisce ireann, established in 2013, is funded through taxation rather than householder water bills (it is a strongly held principle in Ireland that water is free). In contrast, across the Irish Sea in England, privatised water companies operate as uncompetitive monopolies, extracting profit for shareholders while allowing water infrastructure to languish. In2024, Londons private water company Thames Water was responsible for 300,000 hours of raw sewage overflowing into waterways, despite having over 350 treatment plants. The same year, it paidshareholders dividends amounting to 158million. Thames Water has announced water bill increases of 31 per cent beginning 1 April to an annual average of 639 per household.The new use of this site to clean water in Arklow is in stark contrast to its historical uses which excreted a plethora of toxic substances; a gypsum board factory, active between 1964 and 2002, was demolished to make way for the project, and an ammunitions factory for the English Kynoch Company factory was on the site before that. Even thesoil itself reclaimed from the sea during the 19th century is likely contaminated spoil from the Avoca mines. Both the weapons and extracted copper and sulphur that continue to leave their traces inArklow were used by England for imperial gain. Large rusting cylindrical tanks that held industrial waste remain on the site areminder of the toxicity that came before.Today, the river runs clean for the first time in over a hundred years. There are hopes that the oysters will return.