How a planetarium show discovered a spiral at the edge of our solar system

If you’ve ever flown through outer space, at least while watching a documentary or a science fiction film, you’ve seen how artists turn astronomical findings into stunning visuals. But in the process of visualizing data for their latest planetarium show, a production team at New York’s American Museum of Natural History made a surprising discovery of their own: a trillion-and-a-half mile long spiral of material drifting along the edge of our solar system.

“So this is a really fun thing that happened,” says Jackie Faherty, the museum’s senior scientist.

Last winter, Faherty and her colleagues were beneath the dome of the museum’s Hayden Planetarium, fine-tuning a scene that featured the Oort cloud, the big, thick bubble surrounding our Sun and planets that’s filled with ice and rock and other remnants from the solar system’s infancy. The Oort cloud begins far beyond Neptune, around one and a half light years from the Sun. It has never been directly observed; its existence is inferred from the behavior of long-period comets entering the inner solar system. The cloud is so expansive that the Voyager spacecraft, our most distant probes, would need another 250 years just to reach its inner boundary; to reach the other side, they would need about 30,000 years.

The 30-minute show, Encounters in the Milky Way, narrated by Pedro Pascal, guides audiences on a trip through the galaxy across billions of years. For a section about our nascent solar system, the writing team decided “there’s going to be a fly-by” of the Oort cloud, Faherty says. “But what does our Oort cloud look like?”

To find out, the museum consulted astronomers and turned to David Nesvorný, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. He provided his model of the millions of particles believed to make up the Oort cloud, based on extensive observational data.

“Everybody said, go talk to Nesvorný. He’s got the best model,” says Faherty. And “everybody told us, ‘There’s structure in the model,’ so we were kind of set up to look for stuff,” she says.

The museum’s technical team began using Nesvorný’s model to simulate how the cloud evolved over time. Later, as the team projected versions of the fly-by scene into the dome, with the camera looking back at the Oort cloud, they saw a familiar shape, one that appears in galaxies, Saturn’s rings, and disks around young stars.

“We’re flying away from the Oort cloud and out pops this spiral, a spiral shape to the outside of our solar system,” Faherty marveled. “A huge structure, millions and millions of particles.”

She emailed Nesvorný to ask for “more particles,” with a render of the scene attached. “We noticed the spiral of course,” she wrote. “And then he writes me back: ‘what are you talking about, a spiral?’”

While fine-tuning a simulation of the Oort cloud, a vast expanse of ice material leftover from the birth of our Sun, the ‘Encounters in the Milky Way’ production team noticed a very clear shape: a structure made of billions of comets and shaped like a spiral-armed galaxy, seen here in a scene from the final Space ShowMore simulations ensued, this time on Pleiades, a powerful NASA supercomputer. In high-performance computer simulations spanning 4.6 billion years, starting from the Solar System’s earliest days, the researchers visualized how the initial icy and rocky ingredients of the Oort cloud began circling the Sun, in the elliptical orbits that are thought to give the cloud its rough disc shape. The simulations also incorporated the physics of the Sun’s gravitational pull, the influences from our Milky Way galaxy, and the movements of the comets themselves.

In each simulation, the spiral persisted.

“No one has ever seen the Oort structure like that before,” says Faherty. Nesvorný “has a great quote about this: ‘The math was all there. We just needed the visuals.’”

An illustration of the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud in relation to our solar system.As the Oort cloud grew with the early solar system, Nesvorný and his colleagues hypothesize that the galactic tide, or the gravitational force from the Milky Way, disrupted the orbits of some comets. Although the Sun pulls these objects inward, the galaxy’s gravity appears to have twisted part of the Oort cloud outward, forming a spiral tilted roughly 30 degrees from the plane of the solar system.

“As the galactic tide acts to decouple bodies from the scattered disk it creates a spiral structure in physical space that is roughly 15,000 astronomical units in length,” or around 1.4 trillion miles from one end to the other, the researchers write in a paper that was published in March in the Astrophysical Journal. “The spiral is long-lived and persists in the inner Oort Cloud to the present time.”

“The physics makes sense,” says Faherty. “Scientists, we’re amazing at what we do, but it doesn’t mean we can see everything right away.”

It helped that the team behind the space show was primed to look for something, says Carter Emmart, the museum’s director of astrovisualization and director of Encounters. Astronomers had described Nesvorný’s model as having “a structure,” which intrigued the team’s artists. “We were also looking for structure so that it wouldn’t just be sort of like a big blob,” he says. “Other models were also revealing this—but they just hadn’t been visualized.”

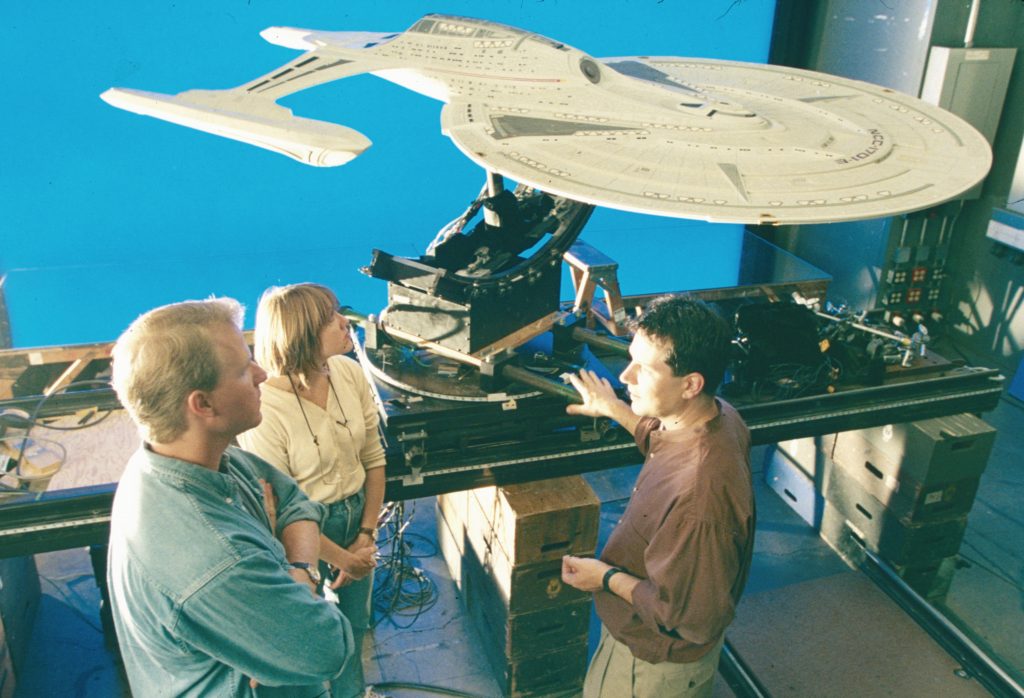

The museum’s attempts to simulate nature date back to its first habitat dioramas in the early 1900s, which brought visitors to places that hadn’t yet been captured by color photos, TV, or the web. The planetarium, a night sky simulator for generations of would-be scientists and astronauts, got its start after financier Charles Hayden bought the museum its first Zeiss projector. The planetarium now boasts one of the world’s few Zeiss Mark IX systems.

Still, these days the star projector is rarely used, Emmart says, now that fulldome laser projectors can turn the old static starfield into 3D video running at 60 frames per second. The Hayden boasts six custom-built Christie projectors, part of what the museum’s former president called “the most advanced planetarium ever attempted.”

In about 1.3 million years, the star system Gliese 710 is set to pass directly through our Oort Cloud, an event visualized in a dramatic scene in ‘Encounters in the Milky Way.’ During its flyby, our systems will swap icy comets, flinging some out on new paths.Emmart recalls how in 1998, when he and other museum leaders were imagining the future of space shows at the Hayden—now with the help of digital projectors and computer graphics—there were questions over how much space they could try to show.

“We’re talking about these astronomical data sets we could plot to make the galaxy and the stars,” he says. “Of course, we knew that we would have this star projector, but we really wanted to emphasize astrophysics with this dome video system. I was drawing pictures of this just to get our heads around it and noting the tip of the solar system to the Milky Way is about 60 degrees. And I said, what are we gonna do when we get outside the Milky Way?’

“ThenNeil Degrasse Tyson “goes, ‘whoa, whoa, whoa, Carter, we have enough to do. And just plotting the Milky Way, that’s hard enough.’ And I said, ‘well, when we exit the Milky Way and we don’t see any other galaxies, that’s sort of like astronomy in 1920—we thought maybe the entire universe is just a Milky Way.'”

“And that kind of led to a chaotic discussion about, well, what other data sets are there for this?” Emmart adds.

The museum worked with astronomer Brent Tully, who had mapped 3500 galaxies beyond the Milky Way, in collaboration with the National Center for Super Computing Applications. “That was it,” he says, “and that seemed fantastical.”

By the time the first planetarium show opened at the museum’s new Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000, Tully had broadened his survey “to an amazing” 30,000 galaxies. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey followed—it’s now at data release 18—with six million galaxies.

To build the map of the universe that underlies Encounters, the team also relied on data from the European Space Agency’s space observatory, Gaia. Launched in 2013 and powered down in March of this year, Gaia brought an unprecedented precision to our astronomical map, plotting the distance between 1.7 billion stars. To visualize and render the simulated data, Jon Parker, the museum’s lead technical director, relied on Houdini, a 3D animation tool by Toronto-based SideFX.

The goal is immersion, “whether it’s in front of the buffalo downstairs, and seeing what those herds were like before we decimated them, to coming in this room and being teleported to space, with an accurate foundation in the science,” Emmart says. “But the art is important, because the art is the way to the soul.”

The museum, he adds, is “a testament to wonder. And I think wonder is a gateway to inspiration, and inspiration is a gateway to motivation.”

Three-D visuals aren’t just powerful tools for communicating science, but increasingly crucial for science itself. Software like OpenSpace, an open source simulation tool developed by the museum, along with the growing availability of high-performance computing, are making it easier to build highly detailed visuals of ever larger and more complex collections of data.

“Anytime we look, literally, from a different angle at catalogs of astronomical positions, simulations, or exploring the phase space of a complex data set, there is great potential to discover something new,” says Brian R. Kent, an astronomer and director of science communications at National Radio Astronomy Observatory. “There is also a wealth of astronomics tatical data in archives that can be reanalyzed in new ways, leading to new discoveries.”

As the instruments grow in size and sophistication, so does the data, and the challenge of understanding it. Like all scientists, astronomers are facing a deluge of data, ranging from gamma rays and X-rays to ultraviolet, optical, infrared, and radio bands.

Our Oort cloud, a shell of icy bodies that surrounds the solar system and extends one-and-a-half light years in every direction, is shown in this scene from ‘Encounters in the Milky Way’ along with the Oort clouds of neighboring stars. The more massive the star, the larger its Oort cloud“New facilities like the Next Generation Very Large Array here at NRAO or the Vera Rubin Observatory and LSST survey project will generate large volumes of data, so astronomers have to get creative with how to analyze it,” says Kent.

More data—and new instruments—will also be needed to prove the spiral itself is actually there: there’s still no known way to even observe the Oort cloud.

Instead, the paper notes, the structure will have to be measured from “detection of a large number of objects” in the radius of the inner Oort cloud or from “thermal emission from small particles in the Oort spiral.”

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a powerful, U.S.-funded telescope that recently began operation in Chile, could possibly observe individual icy bodies within the cloud. But researchers expect the telescope will likely discover only dozens of these objects, maybe hundreds, not enough to meaningfully visualize any shapes in the Oort cloud.

For us, here and now, the 1.4 trillion mile-long spiral will remain confined to the inside of a dark dome across the street from Central Park.

#how #planetarium #show #discovered #spiralHow a planetarium show discovered a spiral at the edge of our solar system

If you’ve ever flown through outer space, at least while watching a documentary or a science fiction film, you’ve seen how artists turn astronomical findings into stunning visuals. But in the process of visualizing data for their latest planetarium show, a production team at New York’s American Museum of Natural History made a surprising discovery of their own: a trillion-and-a-half mile long spiral of material drifting along the edge of our solar system.

“So this is a really fun thing that happened,” says Jackie Faherty, the museum’s senior scientist.

Last winter, Faherty and her colleagues were beneath the dome of the museum’s Hayden Planetarium, fine-tuning a scene that featured the Oort cloud, the big, thick bubble surrounding our Sun and planets that’s filled with ice and rock and other remnants from the solar system’s infancy. The Oort cloud begins far beyond Neptune, around one and a half light years from the Sun. It has never been directly observed; its existence is inferred from the behavior of long-period comets entering the inner solar system. The cloud is so expansive that the Voyager spacecraft, our most distant probes, would need another 250 years just to reach its inner boundary; to reach the other side, they would need about 30,000 years.

The 30-minute show, Encounters in the Milky Way, narrated by Pedro Pascal, guides audiences on a trip through the galaxy across billions of years. For a section about our nascent solar system, the writing team decided “there’s going to be a fly-by” of the Oort cloud, Faherty says. “But what does our Oort cloud look like?”

To find out, the museum consulted astronomers and turned to David Nesvorný, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. He provided his model of the millions of particles believed to make up the Oort cloud, based on extensive observational data.

“Everybody said, go talk to Nesvorný. He’s got the best model,” says Faherty. And “everybody told us, ‘There’s structure in the model,’ so we were kind of set up to look for stuff,” she says.

The museum’s technical team began using Nesvorný’s model to simulate how the cloud evolved over time. Later, as the team projected versions of the fly-by scene into the dome, with the camera looking back at the Oort cloud, they saw a familiar shape, one that appears in galaxies, Saturn’s rings, and disks around young stars.

“We’re flying away from the Oort cloud and out pops this spiral, a spiral shape to the outside of our solar system,” Faherty marveled. “A huge structure, millions and millions of particles.”

She emailed Nesvorný to ask for “more particles,” with a render of the scene attached. “We noticed the spiral of course,” she wrote. “And then he writes me back: ‘what are you talking about, a spiral?’”

While fine-tuning a simulation of the Oort cloud, a vast expanse of ice material leftover from the birth of our Sun, the ‘Encounters in the Milky Way’ production team noticed a very clear shape: a structure made of billions of comets and shaped like a spiral-armed galaxy, seen here in a scene from the final Space ShowMore simulations ensued, this time on Pleiades, a powerful NASA supercomputer. In high-performance computer simulations spanning 4.6 billion years, starting from the Solar System’s earliest days, the researchers visualized how the initial icy and rocky ingredients of the Oort cloud began circling the Sun, in the elliptical orbits that are thought to give the cloud its rough disc shape. The simulations also incorporated the physics of the Sun’s gravitational pull, the influences from our Milky Way galaxy, and the movements of the comets themselves.

In each simulation, the spiral persisted.

“No one has ever seen the Oort structure like that before,” says Faherty. Nesvorný “has a great quote about this: ‘The math was all there. We just needed the visuals.’”

An illustration of the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud in relation to our solar system.As the Oort cloud grew with the early solar system, Nesvorný and his colleagues hypothesize that the galactic tide, or the gravitational force from the Milky Way, disrupted the orbits of some comets. Although the Sun pulls these objects inward, the galaxy’s gravity appears to have twisted part of the Oort cloud outward, forming a spiral tilted roughly 30 degrees from the plane of the solar system.

“As the galactic tide acts to decouple bodies from the scattered disk it creates a spiral structure in physical space that is roughly 15,000 astronomical units in length,” or around 1.4 trillion miles from one end to the other, the researchers write in a paper that was published in March in the Astrophysical Journal. “The spiral is long-lived and persists in the inner Oort Cloud to the present time.”

“The physics makes sense,” says Faherty. “Scientists, we’re amazing at what we do, but it doesn’t mean we can see everything right away.”

It helped that the team behind the space show was primed to look for something, says Carter Emmart, the museum’s director of astrovisualization and director of Encounters. Astronomers had described Nesvorný’s model as having “a structure,” which intrigued the team’s artists. “We were also looking for structure so that it wouldn’t just be sort of like a big blob,” he says. “Other models were also revealing this—but they just hadn’t been visualized.”

The museum’s attempts to simulate nature date back to its first habitat dioramas in the early 1900s, which brought visitors to places that hadn’t yet been captured by color photos, TV, or the web. The planetarium, a night sky simulator for generations of would-be scientists and astronauts, got its start after financier Charles Hayden bought the museum its first Zeiss projector. The planetarium now boasts one of the world’s few Zeiss Mark IX systems.

Still, these days the star projector is rarely used, Emmart says, now that fulldome laser projectors can turn the old static starfield into 3D video running at 60 frames per second. The Hayden boasts six custom-built Christie projectors, part of what the museum’s former president called “the most advanced planetarium ever attempted.”

In about 1.3 million years, the star system Gliese 710 is set to pass directly through our Oort Cloud, an event visualized in a dramatic scene in ‘Encounters in the Milky Way.’ During its flyby, our systems will swap icy comets, flinging some out on new paths.Emmart recalls how in 1998, when he and other museum leaders were imagining the future of space shows at the Hayden—now with the help of digital projectors and computer graphics—there were questions over how much space they could try to show.

“We’re talking about these astronomical data sets we could plot to make the galaxy and the stars,” he says. “Of course, we knew that we would have this star projector, but we really wanted to emphasize astrophysics with this dome video system. I was drawing pictures of this just to get our heads around it and noting the tip of the solar system to the Milky Way is about 60 degrees. And I said, what are we gonna do when we get outside the Milky Way?’

“ThenNeil Degrasse Tyson “goes, ‘whoa, whoa, whoa, Carter, we have enough to do. And just plotting the Milky Way, that’s hard enough.’ And I said, ‘well, when we exit the Milky Way and we don’t see any other galaxies, that’s sort of like astronomy in 1920—we thought maybe the entire universe is just a Milky Way.'”

“And that kind of led to a chaotic discussion about, well, what other data sets are there for this?” Emmart adds.

The museum worked with astronomer Brent Tully, who had mapped 3500 galaxies beyond the Milky Way, in collaboration with the National Center for Super Computing Applications. “That was it,” he says, “and that seemed fantastical.”

By the time the first planetarium show opened at the museum’s new Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000, Tully had broadened his survey “to an amazing” 30,000 galaxies. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey followed—it’s now at data release 18—with six million galaxies.

To build the map of the universe that underlies Encounters, the team also relied on data from the European Space Agency’s space observatory, Gaia. Launched in 2013 and powered down in March of this year, Gaia brought an unprecedented precision to our astronomical map, plotting the distance between 1.7 billion stars. To visualize and render the simulated data, Jon Parker, the museum’s lead technical director, relied on Houdini, a 3D animation tool by Toronto-based SideFX.

The goal is immersion, “whether it’s in front of the buffalo downstairs, and seeing what those herds were like before we decimated them, to coming in this room and being teleported to space, with an accurate foundation in the science,” Emmart says. “But the art is important, because the art is the way to the soul.”

The museum, he adds, is “a testament to wonder. And I think wonder is a gateway to inspiration, and inspiration is a gateway to motivation.”

Three-D visuals aren’t just powerful tools for communicating science, but increasingly crucial for science itself. Software like OpenSpace, an open source simulation tool developed by the museum, along with the growing availability of high-performance computing, are making it easier to build highly detailed visuals of ever larger and more complex collections of data.

“Anytime we look, literally, from a different angle at catalogs of astronomical positions, simulations, or exploring the phase space of a complex data set, there is great potential to discover something new,” says Brian R. Kent, an astronomer and director of science communications at National Radio Astronomy Observatory. “There is also a wealth of astronomics tatical data in archives that can be reanalyzed in new ways, leading to new discoveries.”

As the instruments grow in size and sophistication, so does the data, and the challenge of understanding it. Like all scientists, astronomers are facing a deluge of data, ranging from gamma rays and X-rays to ultraviolet, optical, infrared, and radio bands.

Our Oort cloud, a shell of icy bodies that surrounds the solar system and extends one-and-a-half light years in every direction, is shown in this scene from ‘Encounters in the Milky Way’ along with the Oort clouds of neighboring stars. The more massive the star, the larger its Oort cloud“New facilities like the Next Generation Very Large Array here at NRAO or the Vera Rubin Observatory and LSST survey project will generate large volumes of data, so astronomers have to get creative with how to analyze it,” says Kent.

More data—and new instruments—will also be needed to prove the spiral itself is actually there: there’s still no known way to even observe the Oort cloud.

Instead, the paper notes, the structure will have to be measured from “detection of a large number of objects” in the radius of the inner Oort cloud or from “thermal emission from small particles in the Oort spiral.”

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a powerful, U.S.-funded telescope that recently began operation in Chile, could possibly observe individual icy bodies within the cloud. But researchers expect the telescope will likely discover only dozens of these objects, maybe hundreds, not enough to meaningfully visualize any shapes in the Oort cloud.

For us, here and now, the 1.4 trillion mile-long spiral will remain confined to the inside of a dark dome across the street from Central Park.

#how #planetarium #show #discovered #spiral