Nimble-Minded Neanderthals May Have Used These Wooden Spears to Hunt 200,000 Years Ago

New Research

Nimble-Minded Neanderthals May Have Used These Wooden Spears to Hunt 200,000 Years Ago

New research shows that the weapons found in Germany are much younger than previously thought, suggesting they were made by skilled Neanderthal craftspeople

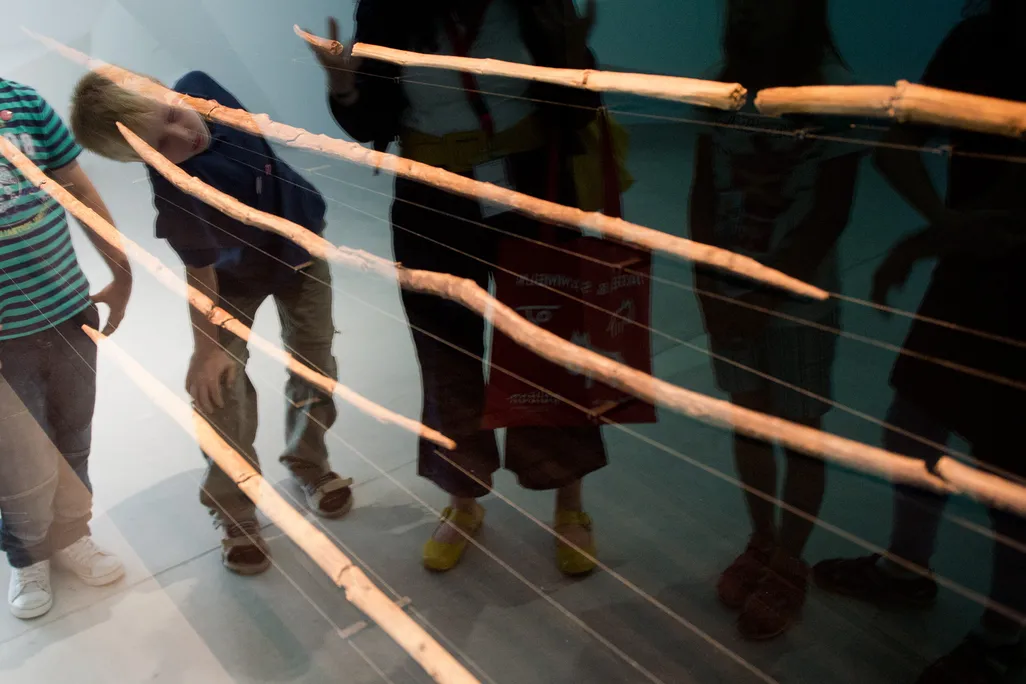

The Schöningen spears on display in Germany

Julian Stratenschulte / Picture Alliance via Getty Images

In the 1990s, archaeologists working near the German town of Schöningen made a remarkable find: a set of well-preserved wooden spears crafted from spruce and pine, along with stone tools and the butchered remains of more than 50 horses.

Researchers initially thought the Schöningen spears were around 400,000 years old and later revised that estimate to roughly 300,000 years old. They suspected the spears—which are among the oldest known complete hunting weapons—belonged to an early human ancestor called Homo heidelbergensis.

Now, however, they’re revising the timeline once again: According to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances, the spears are around 200,000 years old—much younger than previously thought.

The new date suggests the weapons may have belonged to Neanderthals, instead of H. heidelbergensis. This theory makes sense to some researchers because, around the same time, Neanderthals were starting to exhibit more complex behaviors, like making stone tools and deploying sophisticated hunting tactics. During this period, known as the Middle Paleolithic, Neanderthals also began living longer, which suggests that they benefited from these lifestyle and behavior advancements.

Based on the horse remains found at the site, it appears that hunters cleverly trapped them near the edge of a prehistoric lake. Researchers think the spears were carefully hand-made by skilled craftspeople.

“They offer compelling evidence of sophisticated hunting strategies which would have required better cognitive abilities and the development of more complex communication, planning and social structures,” says lead author Jarod Hutson, an archaeologist at Germany’s Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie, in a statement. “The updated timeline for Schöningen now aligns it with a growing number of sites which together indicate a significant leap in early human hunting capabilities during this period.”

If the spears were created and used by humans’ closest prehistoric relatives, this revelation would add to the growing body of evidence that “Neanderthal brain development and social structure were more advanced than previously believed,” writes Austin Harvey of All That’s Interesting.

However, not everyone is confident of the new date—or the theory that the spears belonged to Neanderthals.

“For the moment, I find the arguments interesting, but not absolutely convincing,” says Thomas Terberger, an archaeologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany who wasn’t involved with the research, to the Associated Press’ Adithi Ramakrishnan.

To determine the new timeline, researchers analyzed fossilized freshwater snail shells found in the same layer of dirt as the spears. They honed in on amino acids that were locked in the shells by tiny “trapdoors” called opercula. Because amino acids break down at predictable rates, researchers could use them to estimate the age of the fossils.

This method is known as amino acid geochronology. It’s one of the tools researchers have at their disposal for dating artifacts, along with radiocarbon dating, which measures the amount of radioactive carbon-14 present in organic materials, and luminescence dating, which measures the last time sediments were exposed to sunlight. Even with such techniques, however, precisely estimating the age of artifacts can be challenging.

Anything scientists can do to narrow down the timeframe helps make historic sites “more useful for answering archaeological questions about human evolution and cultural development,” says study co-author Kirsty Penkman, a geochemist at the University of York in England, to Science’s Andrew Curry.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

#nimbleminded #neanderthals #have #used #these

Nimble-Minded Neanderthals May Have Used These Wooden Spears to Hunt 200,000 Years Ago

New Research

Nimble-Minded Neanderthals May Have Used These Wooden Spears to Hunt 200,000 Years Ago

New research shows that the weapons found in Germany are much younger than previously thought, suggesting they were made by skilled Neanderthal craftspeople

The Schöningen spears on display in Germany

Julian Stratenschulte / Picture Alliance via Getty Images

In the 1990s, archaeologists working near the German town of Schöningen made a remarkable find: a set of well-preserved wooden spears crafted from spruce and pine, along with stone tools and the butchered remains of more than 50 horses.

Researchers initially thought the Schöningen spears were around 400,000 years old and later revised that estimate to roughly 300,000 years old. They suspected the spears—which are among the oldest known complete hunting weapons—belonged to an early human ancestor called Homo heidelbergensis.

Now, however, they’re revising the timeline once again: According to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances, the spears are around 200,000 years old—much younger than previously thought.

The new date suggests the weapons may have belonged to Neanderthals, instead of H. heidelbergensis. This theory makes sense to some researchers because, around the same time, Neanderthals were starting to exhibit more complex behaviors, like making stone tools and deploying sophisticated hunting tactics. During this period, known as the Middle Paleolithic, Neanderthals also began living longer, which suggests that they benefited from these lifestyle and behavior advancements.

Based on the horse remains found at the site, it appears that hunters cleverly trapped them near the edge of a prehistoric lake. Researchers think the spears were carefully hand-made by skilled craftspeople.

“They offer compelling evidence of sophisticated hunting strategies which would have required better cognitive abilities and the development of more complex communication, planning and social structures,” says lead author Jarod Hutson, an archaeologist at Germany’s Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie, in a statement. “The updated timeline for Schöningen now aligns it with a growing number of sites which together indicate a significant leap in early human hunting capabilities during this period.”

If the spears were created and used by humans’ closest prehistoric relatives, this revelation would add to the growing body of evidence that “Neanderthal brain development and social structure were more advanced than previously believed,” writes Austin Harvey of All That’s Interesting.

However, not everyone is confident of the new date—or the theory that the spears belonged to Neanderthals.

“For the moment, I find the arguments interesting, but not absolutely convincing,” says Thomas Terberger, an archaeologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany who wasn’t involved with the research, to the Associated Press’ Adithi Ramakrishnan.

To determine the new timeline, researchers analyzed fossilized freshwater snail shells found in the same layer of dirt as the spears. They honed in on amino acids that were locked in the shells by tiny “trapdoors” called opercula. Because amino acids break down at predictable rates, researchers could use them to estimate the age of the fossils.

This method is known as amino acid geochronology. It’s one of the tools researchers have at their disposal for dating artifacts, along with radiocarbon dating, which measures the amount of radioactive carbon-14 present in organic materials, and luminescence dating, which measures the last time sediments were exposed to sunlight. Even with such techniques, however, precisely estimating the age of artifacts can be challenging.

Anything scientists can do to narrow down the timeframe helps make historic sites “more useful for answering archaeological questions about human evolution and cultural development,” says study co-author Kirsty Penkman, a geochemist at the University of York in England, to Science’s Andrew Curry.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

#nimbleminded #neanderthals #have #used #these

·155 Views